I grew up in my family’s dive bar in Grand Rapids, Michigan, a city now affectionately and appropriately called Beer City, U.S.A. I was surrounded by a makeshift family of beer-swilling, goodhearted customers with crooked jaws and scars across their cheeks, people who hopped up on their stools at 6 a.m. and stayed until the afternoon girl counted in her till.

I thought Cheers was a family sitcom. I saw the know-it-all postman, the work-averse accountant, and the salty server in the men and women we affectionately called by their nicknames—Char, Bunny, John Boss, Stinky, Candy, and so many Schmittys that it’s difficult to count. The bar was my extended family, my classroom for storytelling, my connection to a time when a secret passcode allowed German, Polish, Russian, and Lithuanian immigrants to gather in secret, gamble, and shake off the winter and grueling work. This tradition, begun in the 1850s and nurtured through Prohibition and the heyday of the United Auto Workers Union, is still alive today.

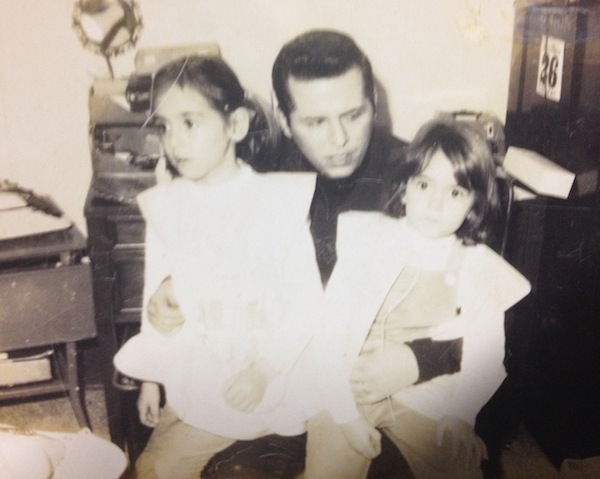

A picture that still hanges in Kale’s Korner Bar of the author and her sister modeling a new sweatshirt design, c. 1984.

When the Germans and Polish settled the Westside of my hometown in the 19th century, no one had money. They took backbreaking jobs, and an epidemic of bone-shaking fevers swept through the town with no end in sight. A German named Kusterer built a brewery on Bridge Street. He advertised his lager as a “family drink,” and Gottlieb Christ opened the first tavern (Bridge Street House, of course) in 1850. When the tavern opened, the fever mysteriously disappeared from Grand Rapids. People saw it not as a coincidence but as a cause and effect.

But every cure calls for a new disease. While the Germans and Polish employed their own and slowly began to build an empire of taverns and breweries along Bridge Street, there were opponents. Not everyone wanted their city to be Beer City. And Michigan went dry in 1918, two years before the national ban. On the Westside, we still speculate it was wealthy Eastsiders who wanted to put a stop to working-class German enterprise, but that’s probably just old ethnic prejudice at work.

In the basement of almost every single Bridge Street tavern from that time, you will find speakeasies. The city was technically dry, but keeping the Eastern Europeans from their medicine? The police say it was “simply unenforceable” on the Westside. It’s this wild, back-alley dealing reputation that Westsiders embrace and Eastsiders abhor, but that spirit has made our bars legendary and the setting for tales of redemption and loss we continue to tell today.

The author’s grandfather, Bob, holding the author’s mother and aunt in the Konkle’s back room, c. 1967.

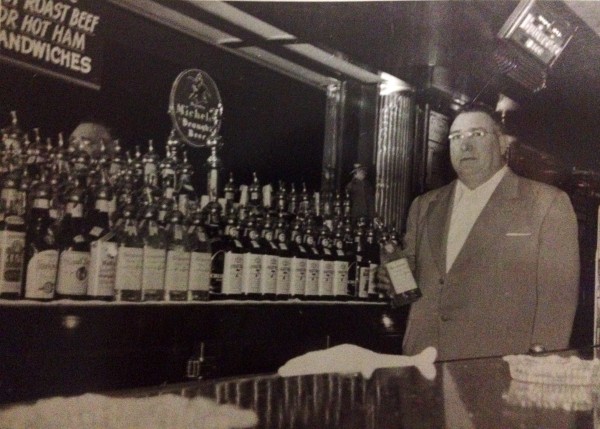

The son of a German immigrant, my great-grandfather Vernon “Mike” Konkle opened and operated our family’s first bar—Konkle’s Bar on Bridge Street—around 1950. My grandfather, Bob Kale, the son of a Polish immigrant, fell in love with one of Mike’s daughters.

Mike taught Bob the trade. Serving beers gave Bob, a directionless greaser on a motorcycle headed for Dead Man’s Curve, a chance at a new start. He took it: Bob worked 16-hour days, never drank on the job, was trained and loved so well by Mike that he could have been a blood relative.

But with every fairy tale comes the cautionary tale: When Mike died, Bob hit the bottle. There were late-night parties and arguments in the streets, and my grandmother hit a manic depression, and they couldn’t recover. Bob was fired, bouncing around to other bars with a dream of starting his own. But this time, alcohol got in the way.

My mother, Bob’s first kid, remembers whole weeks going by with no parental supervision, and when her mother finally returned, she was drunk and tired. My grandparents divorced and later, after my mother left home, she married a man who also drank—my father—whom I only met once.

And yet, alcohol saved Bob a second time.

My grandfather was able to clean up, remarry, and finally open his own place, Kale’s Korner Bar, in 1981, a block away from Konkle’s. He bought a house, and my mom, my sister, and I moved into the basement, along with a couple of other relatives. We had four sprawling generations packed in a brown ranch-style house, all of us taking turns working at the bar. I remember my grandfather waking us kids up at 3 a.m. to help close the bar. We emptied change from the pinball machines and shook out the mats. I may have been generations removed from my German and Polish immigrant ancestors, but we were still living like they had, holding onto what we had to make it in America.

When a homeless man or woman came to my grandfather asking for some change, he would look the person up and down and say instead, “How about a job at the bar?” He knew the value of second chances and having family, whether real or manufactured. That’s the image of Beer City, U.S.A. that my mind conjures: people in it together, finding community however they can.

The bar in Grand Rapids made me everything I am, outfitted me in free Budweiser T-shirts, and connected me to all the first-generation Germans, Poles, and Russians who ever sought refuge in a beer hall. It gave me a chance to hear all the stories about how we could fail, laugh about it with dark-edged humor, and continue to face forward into the biting Michigan wind.

A. Wolfe is a writer and filmmaker in Los Angeles with work in Vice and other publications. An emerging writer fellow for A Public Space in 2014, she is currently completing her first novel and collecting her family stories for a book. She wrote this for What It Means to Be American, a national conversation hosted by the Smithsonian and Zócalo Public Square.

*Family photos courtesy of A. Wolfe. Exterior photo of Konkle’s Bar courtesy of Russell Sekeet.