“Where do you get your ideas?”

“Can you tell us about cartoons you’ve had censored?”

“Is there a line you won’t cross?”

And more recently: “Don’t you wish American satirists could take more liberties like the French?”

Nowadays, people seem to assume that practicing the craft of political cartooning is an incredibly delicate balancing act akin to handling unexploded cluster bombs, a constant exercise in repression and frustration.

I almost hate to disappoint those looking for a good story about the forces of neo-McCarthyism or puritanism run amok, but the truth is, I draw exactly what I want every single week.

In 15 years, I’ve had only two regular clients decline to publish a cartoon. One of my strips supporting vaccines was not well received by a website whose publisher subscribed to anti-vaccination theories. Another cartoon poked fun at newspapers that refused to print a Doonesbury comic about mandatory transvaginal ultrasounds. One of my smaller alt-weekly clients was owned by such a paper, and my editor, though personally sympathetic, said it put him in an awkward situation.

Granted, the tremendous freedoms I enjoy are partly due to the fact that I don’t work for a daily newspaper, but instead self-syndicate my cartoons to alternative newsweeklies, political magazines, and various websites. Most of these publications have a more intelligent and irreverent sensibility than the family-friendly conventional wisdom of the dailies. Fortunately, there are enough such media outlets willing to pay for my work, thus allowing me to make a living for now. For a while, the possibility that the internet simply wouldn’t support political cartooning was the biggest challenge I faced. After a decade in which huge numbers of cartoonists were driven from the profession for lack of funding, some websites have finally begun paying for cartoons.

The first step of writing a cartoon involves hours of news consumption, with the goal of finding something anger-inducing (or at least ridiculous) enough to make me want to draw about it. The next step typically involves staring into space or lying down with my eyes closed. Often, it will look like I’m napping when I’m really thinking. Sometimes an actual nap will occur.

With luck, by the end of this process, I will have a bunch of random thoughts written on a piece of paper, usually in the form of interconnected bubbles that may or may not be all that coherent. At this point, I assess the bubbles to see if I have enough material for a four-panel comic, the usual layout for my strip. Usually I need to do some more thinking.

Once I have enough material, the trick is winnowing everything down for brevity. The chiseling and refining can seem endless, as there are always ways to make a script flow better. I go through several rough sketches and have the writing complete before setting mechanical pencil to Bristol board to draw the final cartoon. The artwork always comes last.

While the process is the same every week, the circumstances vary tremendously. Some weeks I’m so incensed about an issue that I can barely contain myself. Other weeks, the news seems repetitive and boring. These are the hardest. Having to be creative when I feel ill, tired, or upset about something (other the news) can be difficult.

A larger and more external challenge faced by many cartoonists, of course, is the threat of terrorism. Countering an opinion with acts of violence or threats of violence, whether they come from ISIS or basement-dwelling internet trolls, has no place in free society.

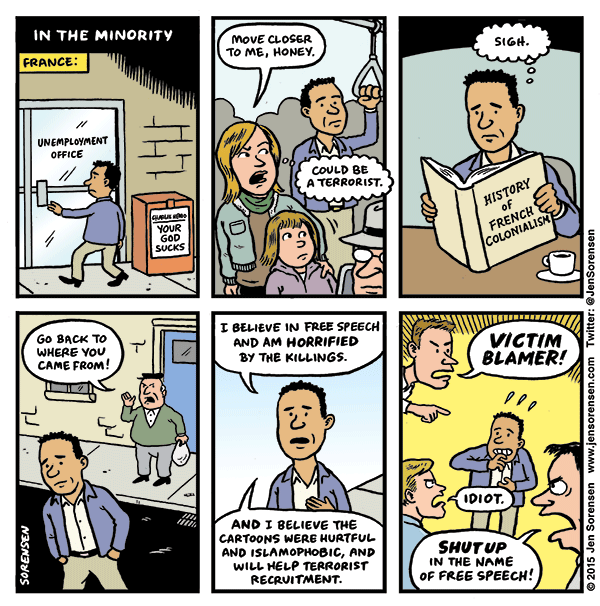

As for how to respond, I probably have a more complicated view than some of my colleagues. My background is in cultural anthropology. I enjoy seeking out perspectives beyond my own and thinking about how messages are perceived cross-culturally. I’ve seen how easy it is for members of one group to declare something objectively “funny” while seeming clueless about its exclusionary message. Humor is in the mind—and sense of social alienation—of the beholder.

Many First Amendment hawks seem to take a reactionary approach to attacks on cartoonists, asserting that drawing ever more “offensive” cartoons is the only way to defend free speech. But free speech isn’t a game of chicken. Thankfully, it’s much bigger and better than that. The extremists win if they make us more extreme.

Being a political cartoonist reminds me a little of being a doctor, in that the golden rule I try to follow is “do no harm.” Cartoons have the power to humiliate and ostracize, and we’re at our best when wielding that power against those who truly deserve it—those who abuse their own power. These days, my targets often are irresponsible corporations, their political enablers, and members of groups blind to their own social advantages. Cartoons, while simple in appearance, should illuminate and explain rather than reinforce simplistic notions. They should punch up, not down.

Some have made the argument that we cannot—must not—question Islamophobic cartoons, lest we divert blame away from the terrorists and detract from the cause of free speech. I don’t think condemning terrorism and questioning the merits of some cartoons are contradictory ideas. In fact, shouting down anyone who tries to do so seems opposed to the very principles of free expression.

It was in this spirit that I was compelled to draw one of my most controversial, popular, and satisfying cartoons of late, exploring the plight of Muslims in France who deplored the attacks and support free speech while also having reservations about Charlie Hebdo. I had interviewed a few Muslim cartoonists and read others’ reactions online, and found the complexity and thoughtfulness of their responses illuminating. It seemed to find a following among readers who are frequently reminded they are on the outside looking in.

While we profess to support cartoonists’ rights in the West, we often overlook the many editorial cartoonists around the world who are routinely persecuted for challenging political elites. Well-known Malaysian cartoonist Zunar was recently jailed (then released) for tweeting a drawing alleging corruption in the country’s judicial system. As I write this, Iranian artist Atena Farghadani is in frail condition from a hunger strike while being detained for drawing politicians as a bunch of animals.

Compared to these artists, I feel lucky that my biggest challenge is figuring out how to fill that big blank piece of Bristol board every week.

Jen Sorensen is the winner of the 2014 Herblock Prize and a 2013 Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for Editorial Cartooning. She is also the comics editor for the Graphic Culture section on Fusion.net. Follow her on Twitter at @JenSorensen. She wrote this for “Open Art,” an arts engagement project of the Getty and Zócalo Public Square.

*Lead photo courtesy of Brendan DeBrincat. Interior cartoon by Jen Sorensen.