Twenty-five years later, Cohen has collected over 50,000 snapshots—personal amateur photographs—that were lost, discarded, or disowned by their original owners.

Cohen acquired them from flea markets, eBay, dealers, and boxes sent to him on consignment. While he has little formal art historical training—he works now as an investor—he has always been a collector and long interested in amateur and professional photography of the 20th century. At the start of that era, the snapshot was still a new format, made possible only when the Kodak camera went on the market in 1888.

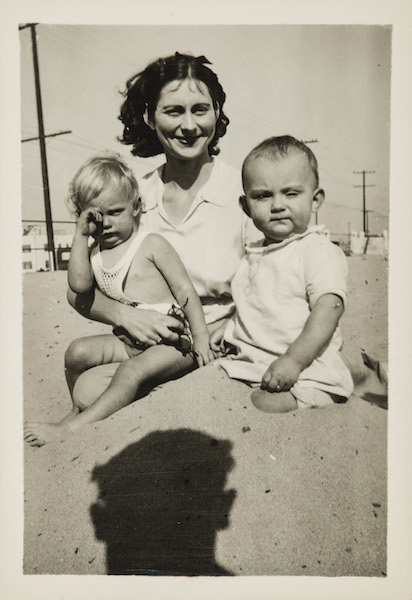

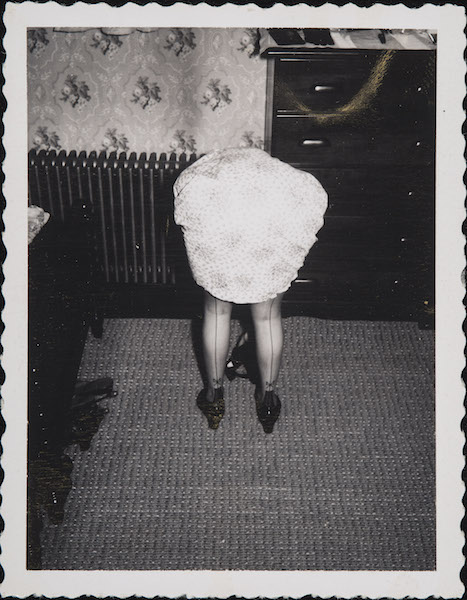

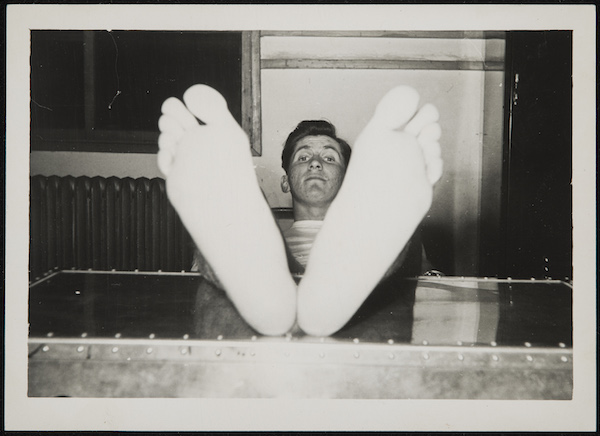

Cohen didn’t think much at first about how he chose his examples. Nor did he think about organizing his quickly growing trove. When he began to do so, and especially when he hired assistants to help him sort, he realized that the photos could be grouped into definite—though sometimes odd—categories: “People on Poles,” for example, or “Photographers’ Shadows,” or “Women in Trees.”

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which was the beneficiary of the largest gift to a museum from this collection—over 1,000 pictures—preserved these labels in its exhibition “Unfinished Stories: Snapshots from the Peter J. Cohen Collection.” Ranging across space and time, the categories reveal unexpected leitmotifs of different lives. The result is a kind of “anthropology of the ordinary,” according to Kristen Gresh, who curated the MFA exhibit with Karen E. Haas.

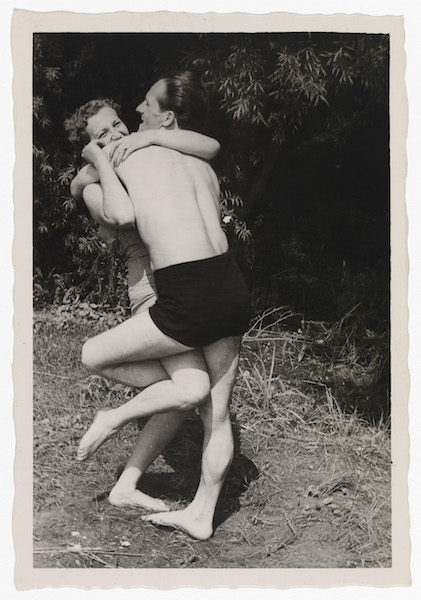

Cohen explained his own deepening understanding, for example, of how women in the 20th century used snapshots to enhance their independence and their relationships with other women. He also noticed “a terrific sense of playfulness and humor in American amateur photography” as compared to snapshots from other parts of the world.

Aesthetic findings surfaced as well. One of the first categories that Cohen recognized in his collecting was the double-exposed picture. Gresh found this group “particularly fascinating” because “they attest to what photography is capable of.” A double exposure can only be created with the camera, she pointed out. “It’s really what the medium is about.”

The snapshot isn’t often considered “fine art,” but that exclusion is part of the point, according to Gresh. “Snapshots in a museum collection can challenge us to think about the boundaries we put on the category of photography,” she said. The fact that “the photograph is accessible and democratic” is a “fundamental part” of its history. And even if unknown people behind the camera didn’t consider themselves artists, they (and their subjects) created images of enduring aesthetic interest.

Today’s photographic technology makes that creativity more accessible than ever, as people snap, crop, and filter pictures on their phones. Yet few of those images become physical objects that future collectors could pick through in a box at a flea market. Cohen worries about this development. “I advise every younger person I meet,” he said, to “pick out one out of every 10 [photos] that they like and print them out in one shape or another.”

Cohen, meanwhile, is still collecting. And categorizing. Recently, he said, he went back through his boxes to assemble a group of people standing on one leg. He continues to rearrange labels and rummage through piles. “The universe expands the more you look,” Cohen explained. “I believe that’s true in everything.”

About 300 photographs are on display in “Unfinished Stories: Snapshots from the Peter J. Cohen Collection” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through February 21, 2016.

*Images courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Peter J. Cohen.