When I first met Harry Fukuhara, in 1994, he was orchestrating a Tokyo press conference for Japanese Foreign Ministry officials, former Jewish refugees from the Holocaust, and veterans of the Japanese-American 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The groups were there to commemorate the separate threads connecting them to the Holocaust. The Foreign Ministry officials were belatedly acknowledging a renegade consul, Chiune Sugihara, who had issued approximately two thousand transit visas to desperate Jewish refugees in Kaunas, Lithuania, when he was stationed there in 1940. Several of these individuals—now elderly Americans and Canadians—were visiting Japan for the first time in 50 years. The 442nd veterans had helped liberate part of Dachau. Among the people involved in this “Unlikely Liberators” tour, the only person who seemed at ease was the man who bore no apparent connection to the events: Harry.

When I first met Harry Fukuhara, in 1994, he was orchestrating a Tokyo press conference for Japanese Foreign Ministry officials, former Jewish refugees from the Holocaust, and veterans of the Japanese-American 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The groups were there to commemorate the separate threads connecting them to the Holocaust. The Foreign Ministry officials were belatedly acknowledging a renegade consul, Chiune Sugihara, who had issued approximately two thousand transit visas to desperate Jewish refugees in Kaunas, Lithuania, when he was stationed there in 1940. Several of these individuals—now elderly Americans and Canadians—were visiting Japan for the first time in 50 years. The 442nd veterans had helped liberate part of Dachau. Among the people involved in this “Unlikely Liberators” tour, the only person who seemed at ease was the man who bore no apparent connection to the events: Harry.

Harry was present as a favor to a friend and seemed to know everyone. He circulated among the crowd, using flawless Japanese and native English. Bowing to the Japanese and chatting with the North Americans, Harry ushered the foreigners towards the media spotlight. Rarely had I seen anyone so bilingual and adept with different cultural styles. Was he Japanese or American? I was not certain.

I soon learned that the white-haired gentleman with ramrod posture and cosmopolitan grace was a retired U.S. Army colonel and specialist in military intelligence. His impeccable Japanese had first been honed during five years in pre-war Japan as a teenager. Today, many would regard this bicultural and bilingual background as an enviable advantage. But in the late 1930s and early 1940s, it made him suspect in both nations.

Born in Seattle in 1920, Harry Katsuharu Fukuhara was the son of Japanese immigrants to America, a generation called Nisei. He grew up hearing Japanese at home and attending language school, but would never have become fluent had his mother not moved the family to her native Hiroshima in 1933 upon the death of Harry’s father.

Once in Japan, Harry and his family were considered Amerika-gaeri—returnees to Japan from America. The term implied merely a sojourn abroad, but no matter how quickly they returned, the Amerika-gaeri were regarded as less than wholly Japanese. It was correctly assumed that America had changed them.

Although many Nisei held dual citizenship, Harry carried only an American passport. He did not view himself as a returnee and railed against his mother’s decision. Harry was ethnically Japanese but not a Japanese; he was an American by birth, law, upbringing, and inclination. This status was a predicament in an increasingly anti-American Japan already at war in China. Nisei, thousands of whom had been sent to Japan for part of their education, were singled out and bullied by peers and strangers. Harry found himself defending the United States to classmates and teachers. “I did not like it in Japan,” he said. “I did not like Japan even before I arrived.” Nothing Harry experienced there changed his mind. As soon as he graduated high school in 1938, he boarded a steamship alone for Seattle, after an affectionate parting from his mother and three brothers.

Upon arriving back in his beloved America, Harry received a chilly welcome. Even his best friend’s family rejected him. He discovered at 18 what he had not been sensitive to earlier. The state of Washington had a long history of anti-Japanese legislation, rooted in the fear of a “Yellow Peril” that reflected a stereotypical view of Asians as invasive “others.” As Japanese aggression in China increased, anti-Japanese sentiment escalated at home. Regarded as an American in Japan, Harry was perceived as a Japanese national in his native land.

Three years later, Harry was living in Los Angeles when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Fear-mongering and racial hysteria enveloped the nation. When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, he authorized the removal of 120,000 ethnic Japanese, two-thirds of whom were American citizens, from the region. Less than three months later, Harry entered the Tulare Assembly Center, a fairgrounds-turned-transit camp, in California. Shortly after, he was incarcerated at Gila River, Arizona, the location of one of 10 internment camps dispersed throughout America’s most desolate regions.

In camp, the community divided. Owing to his years in Japan, Harry was considered a Kibei, a Nisei educated in Japan who had returned to America. The Kibei, often more fluent in Japanese than English from years in Japan, were looked down upon by the Nisei as awkward Americans. Alienated from their nation of birth and derided among those of their shared heritage, some Kibei espoused loyalty to Japan in defiance. In Harry’s mind, he was still an American first and a Nisei second.

But the time in camp changed Harry. For the first time in his life, he questioned his own behavior. “I possessed more than the average bitterness against everybody and everything,” he wrote later to a friend. When an opportunity to leave camp arose, he seized it, enlisting straight from detention into the U.S. Army as a linguist for the incipient, top-secret Military Intelligence Service. By spring 1943, Harry was bound for the Pacific.

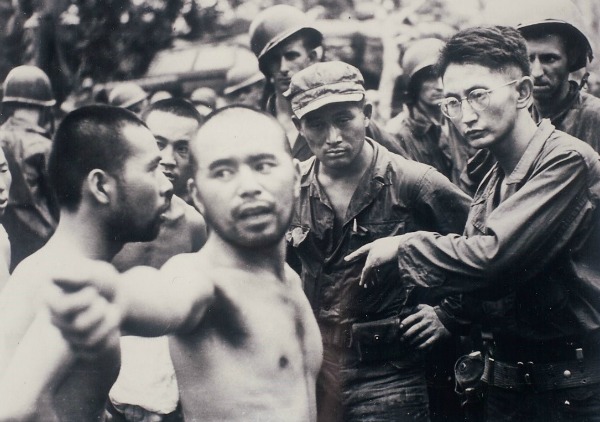

Harry (right), an officer in the U.S. Army, interrogates a Japanese POW in Aitape, New Guinea, in April 1944.

Why did Harry volunteer to fight for the country that had imprisoned him? How could he head to the Pacific when his brothers were most likely in the Japanese Imperial Army? How did he react to his mother’s radiation sickness and brother’s painful death in Hiroshima? These questions inspired my early research, after initially meeting Harry at that press conference in 1994.

In time, Harry would respond in detail. The simple answer is that his identity as an American was forged during his early years, and tested and reinforced in the crucible of war. The reality, however, was far more complicated and anguished. Each successive military operation brought him closer to Japan—he was in Manila when the atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima—but, luckily, Harry never had to fight any of his relatives directly.

In October 1945, two months after the atomic bombs were dropped and Japan surrendered, Harry, by then a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army, set out for Hiroshima to find the family he had not seen in seven years. He had no idea whether they were alive. Even though he had helped the U.S. defeat Japan, he had also made a personal vow upon setting foot in Japan that, whatever happened, he would not forswear his ancestral land. “I felt some responsibility to help postwar Japan recover,” he recalled later.

Harry subsequently spent nearly four decades in Japan as an American military intelligence officer, strengthening relations between the two nations during the Korean War, Vietnam War, and the Cold War. In 1990, at the age of 70, he accepted awards given in the names of the emperor of Japan and the president of the United States.

Harry was a man of conviction, competence and, most remarkably, resilience. At every stage of his life, Harry selected to place his trust in others, although he risked being rejected in two countries. In repudiating his despair in the internment camp, he embraced optimism and joined the military that had imprisoned him. In spurning the hatred so contagious in a war against a ferocious enemy, he sought empathy while never forgetting which side he represented. When he had an opportunity to assert his superior authority in negotiations during the occupation, Harry chose respectful cooperation. “The government couldn’t deny anything that the United States’ military wanted,” said Kiyoshi Hashizaki, a Japanese prefectural official Harry often dealt with, but Harry “didn’t ask for anything impossible.”

On that day in 1994 when I attended that Tokyo press conference to learn more about a diplomat and the refugees he had rescued during World War II, I was seeking to understand how certain individuals surmount cataclysmic challenges, embrace a global vision, and contribute to history. In the end, the man who personified a capacity for humanity beyond the ethnic and national divide was the one I least expected to encounter.

Pamela Rotner Sakamoto is the author of Midnight in Broad Daylight: A Japanese American Family Caught Between Two Worlds, published this month by Harper.

She wrote this for What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian and Zócalo Public Square.

Buy the book: Skylight Books, Powell’s Books, Amazon.

*Lead photo and first interior photo courtesy of Harry Fukuhara. Second interior photo courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.