More than 40 years after her burial in an unmarked Philadelphia grave, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, gospel’s first superstar and its most celebrated crossover figure, is enjoying a burst of Internet celebrity. A video of her playing one of her signature tunes, “Didn’t It Rain,” from a 1964 TV special filmed for British television has been racking up more than 10 million views on YouTube and Facebook. Old and new fans the world over, dazzled by Tharpe’s powerful singing and wildly charismatic guitar playing—all while wearing a proper church lady coat—are proclaiming Tharpe the “godmother” of rock and grumbling over her absence from rock canons like as the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Tharpe is truly great and this recognition is long overdue. Born in the small but thriving town of Cotton Plant, Arkansas, in 1915 and raised partly in Chicago, Tharpe was a musical prodigy of the Church of God in Christ, a Pentecostal denomination that encouraged adherents to express their faith through music. (The honorific “Sister” came from the church.) With her mother, an evangelist, she came of age as a singer and instrumentalist at Southern tent meetings, churches, and religious revivals. She ultimately gained bigger fame in 1938, when she began appearing on the stages of prominent New York nightclubs and recording her music for the Decca label. The 1940s found her fronting Lucky Millinder’s popular swing band and then, in the post-World War II years, playing with the Sam Price Trio, with which she recorded “Strange Things Happening Every Day,” a No. 2 record on the “race” charts (which charted music made for black audiences) in 1945. In the late 1940s, she began collaborating with Newark, N.J.-based singer Marie Knight, with whom she made memorable duets, including “Didn’t It Rain” (1947) and “Up Above My Head” (1948).

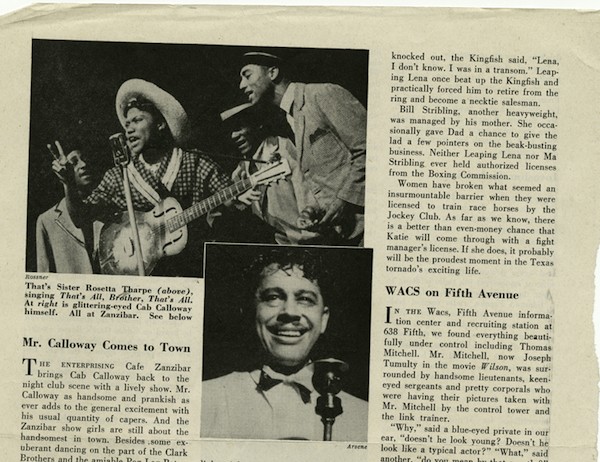

Newspaper coverage of Rosetta Tharpe performing in 1944.

She was so popular, particularly among black audiences, that in the early 1950s she staged her own wedding—her third—in a sold-out ceremony/concert in a Washington, D.C. baseball stadium, playing electric guitar from the outfield while wearing a white wedding gown. An indication of Tharpe’s flamboyance and gift for stagecraft, the stunt was featured in a multi-page photographic spread in Ebony. Fans brought gifts of tableware and even a television set, and the whole affair, which was more radical and perhaps more self-exploitative than anything Madonna ever did—was issued by Decca as a two-disc “wedding album.”

Tharpe didn’t just know how to play the electric guitar, she had a pre-Hendrix gift for making her relationship with the instrument a show in itself. She developed a distinctive finger-picking style and cradled the guitar with an eye toward spectacle. She calibrated her persona carefully, stretching the boundaries of gospel while crafting an image of churched respectability. As a woman who could outplay her male counterparts, she managed the “threat” of her virtuosity to men by undercutting it with disarming humor and a dose of feminine decorum.

By the late 1950s, Tharpe’s star had dimmed, for reasons that included the mercurial nature of the music industry, which demanded the production of new stars and new styles. Tharpe lived comfortably, but modestly, in Philadelphia, reduced to playing small venues and flailing around in search of a sustaining hit that could compete with the rhythm-and-blues records being put out by younger performers.

Paradoxically, her star was then on the rise in Britain and Europe, where earnest music fans wanted the chance to see African-American musicians live. Even as Beatlemania and the British Invasion took hold in the United States, the black American music that had inspired John Lennon, Robert Plant, Keith Richards, and others attracted young people’s attention in England. American kids wanted the Beatles singing “Love Me Do,” but back in the U.K., kids were clamoring to hear the black American blues musicians who had influenced the young British acts.

Ironically, the video that has sparked this recent Rosetta Tharpe “moment” on the Internet is a testimonial to the discovery of Tharpe and other black American musicians by these overwhelming white English audiences in the 1960s. With imprints of U.S. R&B records hard to come by in Britain and mostly unplayed on BBC radio, young Brits flocked to live shows. The much-circulated clip of Tharpe playing “Didn’t It Rain” is from one of these festivals, the American Folk, Blues, and Gospel Caravan, which traveled Britain and Europe in spring 1964, showcasing Tharpe along with the likes of bluesmen Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, and Muddy Waters.

The Blues and Gospel Caravan, as the TV show based on the 1964 tour was dubbed, was filmed at a defunct suburban Manchester, England, railroad station repurposed for the occasion as the fictional town of “Chorltonville,” a half-Hollywood, half-Disneyland fantasy of a (racially segregated) Southern railroad depot. On one side of the tracks are bleachers filled with long-haired white British kids; on the other side, a set of older, more formally attired black musical notables make their way among stage props including a bale of hay, a rocking chair, and two goats tethered to a rail.

Such an old-timey, countrified setting was embarrassingly off-key for a group of seasoned musicians who had performed at Carnegie Hall and on Broadway, but it gave the assembled English kids and folks watching at home the illusion of having journeyed to a mythic backwater and discovered a diamond in the rough, the sources of rock and roll. And although they were amused at being “discovered,” Tharpe and her fellow performers played along with the fans’ fantasy, appreciating the interest. At the beginning of the clip, as pianist Cousin Joe helps Tharpe off a horse-drawn buggy and onto the damp set, you can even hear her remark that she is having “the wonderfulest time in my life.”

In the performance of “Didn’t It Rain” that follows, Tharpe overcomes the cornball sentimentality—or, read less generously, the patronizing racialism—of her surroundings. Dressed in a cape and high heels, she sings and accompanies herself on a white electric SG with the self-assurance of a pro who has seen and done it all before. Her confident, magnetic persona upends expectations both of what a woman was or wasn’t supposed to do (She was handling the guitar with such boldness!) and of how African-Americans were supposed to carry themselves (Look at how sophisticated she seems!). At the same time, attentive viewers might see in Tharpe’s performance a submerged history of black female gospel musicians as musical trailblazers.

In the popularity of the 1964 British TV clip on today’s global social media, we see history repeating itself. That’s because Tharpe’s career, like the career of so many other black American musicians, has been defined by cycles of obscurity and popularity, forgetting and remembering. My own interest in writing a biography of Tharpe was spurred by a then-obscure video of her doing “Up Above My Head”—a clip that is now accessible to anyone with a smartphone. But my curiosity was equally piqued by the realization that I wasn’t alone my ignorance. Her erasure, I found, was a function not merely of the passage of time, but of a tendency in American history to celebrate and elevate the achievements of white men and to “forget” or ignore the brilliance of a figure like Rosetta. Nowhere was this made clearer to me than in a 1970 newspaper clipping I stumbled upon that attributed her sound and style to Elvis Presley—when it was Elvis, and so many others, who emulated Tharpe!

Tharpe’s present moment of fame is unlikely to end soon. This fall, two new theatrical productions—one set to debut off-Broadway, another in Pasadena—will bring elements of Tharpe’s story and a taste of her music to new audiences. Passionate supporters continue to lobby for her recognition by the Rock Hall. And gifted young musicians including Rhiannon Giddens, of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, and Brittany Howard, of the Alabama Shakes, continue to explore Tharpe’s repertoire and draw inspiration from her example.

That unmarked Philadelphia grave? Today it has a rose-colored marble headstone paid for by fans incensed that her legacy had been ignored for so long. Inscribed with a quote from a close friend, it reads, “She would sing until you cried and then she would sing until you danced for joy.” We are not finished crying or dancing.

Gayle Wald is a professor at George Washington University. Her biography of Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Shout, Sister, Shout!, was published by Beacon in 2008.

Buy the book: Skylight Books, Powell’s Books, Amazon.

This was written for What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian and Zócalo Public Square, and is part of Is Rain the Source of Our Imagination?, a project of Zócalo Public Square.

*Lead photo courtesy of AP Photo. Interior photo courtesy of the New York Public Library.