We hear a lot about populism these days. Throughout this primary season, headlines across the country have proclaimed the successes of the “populist” contenders, Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. Without embracing the populist label, moreover, candidates in both parties had already adopted populist tactics by branding their opponents as tools of the “establishment.”

We hear a lot about populism these days. Throughout this primary season, headlines across the country have proclaimed the successes of the “populist” contenders, Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. Without embracing the populist label, moreover, candidates in both parties had already adopted populist tactics by branding their opponents as tools of the “establishment.”

But what is populism, anyway? There is no easy answer, for “populism” describes a political style more than a specific set of ideas or policies, and most commentators apply it to others instead of themselves. Our textbooks usually associate populism with the People’s Party of the 1890s, but a little probing shows that the style has deeper roots than the “free silver” campaigns associated with William Jennings Bryan. Populism refers to political movements that see the great mass of hard-working ordinary people in conflict with a powerful, parasitic few, variously described as “special interests,” the “elite,” the “so-called experts,” and of course, the “establishment.” Populists often insist that plain common sense is a better source of wisdom than elite qualities like advanced education, special training, experience, or a privileged background. Populist movements can be choosy, however, in how they define the “people,” and have frequently excluded women, the very poor, or racial and ethnic minorities. Over time, movements labeled “populist” may have targeted the marginalized about as often as they have the elite, sometimes perceiving an alliance between the idle rich and the undeserving poor at the expense of folks in the middle.

Early populist notions appeared in the rhetoric of 18th-century English radicals who warned of an eternal struggle between liberty, virtue, and the common good against corrupt and tyrannical courtiers. Their ideas spread and evolved in the American Revolution, as the “war for home rule” became a “war over who should rule at home.” An anonymous writer captured the early populist vision in a 1776 pamphlet from New Hampshire entitled “The People the Best Governors,” and many others echoed him. “The people know their own wants and necessities and therefore are best able to rule themselves,” he declared, because “God… made every man equal to his neighbor.” In the opposite corner, many of the founders worried about unchecked popular power and placed numerous curbs on popular power in the Constitution, including the Electoral College, a Senate chosen by state legislatures, and lifetime seats for federal judges.

Despite early stirrings, it was the presidential campaigns of Gen. Andrew Jackson that made the populist style a major force in national politics. To many voters, the presidential candidates of 1824 were a lackluster, squabbling batch of what we’d today call Washington insiders. Known as “Old Hickory,” Jackson was the exception—the humble boy veteran of the Revolution and heroic victor at the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812, who had proved his mettle and virtue against the British and Indians alike. Testifying to his military toughness, his popular nickname also evoked his rural roots and common touch. As one admirer put it, Old Hickory “was the noblest tree in the forest.”

Supporters assured voters that the general’s natural talents far outshone the specious, elite distinctions of his chief competitor, John Quincy Adams—the son of a president, raised in royal capitals, who’d been a member of Phi Beta Kappa, a Harvard professor, and secretary of state. “Although General Jackson has not been educated at foreign courts and reared on sweetmeats from the tables of kings and princes,” sneered one typical editorial, “we think him nevertheless much better qualified to fill the dignified station of president of the United States than Mr. Adams.” In 1824, when Jackson won an electoral plurality but not a majority, and career politicians elected Adams in the House of Representatives, Jackson’s motto for his successful 1828 rematch was ready-made: “Andrew Jackson and the Will of the People.”

Jackson’s inauguration is one of the grand scenes of American history that everyone seems to know about. The speechmaking and oath-taking were solemn and boring, though one high-society matron remembered that the sight of “a free people, collected in their might, silent and tranquil, restrained solely by a moral power, without a shadow around of military force, was majesty, rising to sublimity, and far surpassing the majesty of Kings and Princes, surrounded with armies and glittering in gold.” The White House reception was far otherwise, at least as Mrs. Margaret Bayard Smith described it. “The Majesty of the People had disappeared,” she shuddered. “A rabble, a mob, of boys, negroes, women, children, scrambling fighting, romping …. The whole [White House] had been inundated by the rabble mob.” Mrs. Smith probably exaggerated, and the melee stemmed more from poor planning than innate barbarism, but she perfectly captured the attitude of America’s “better sort” to the mass of farmers, artisans, tradesmen, and laborers who now had final authority in its government. In theory they were sublime, but civilization trembled when they forgot themselves.

Jackson’s conduct in office made official Washington no happier. Mrs. Smith’s husband was president of the Washington branch of the Bank of the United States (a rough counterpart of today’s Federal Reserve), and eventually lost his job when Jackson attacked it. Many of his friends held high appointments in the Adams administration and rightly worried over Jackson’s policy of “rotation in office.” Proclaiming that no one owned an office for life and that “men of intelligence may readily qualify themselves” for government service, the president began to “reform” the government by replacing experienced Adams men with loyal Jacksonians. His policy evolved into the spoils system, in which politics outweighed other qualifications in filling the civil service.

Jackson’s populism appeared most clearly in his policy toward the banking and transportation corporations that were transforming the American economy at the dawn of industrialization. Corporate charters were valuable privileges distributed by legislatures, and state governments often shared corporate ownership with private investors. Jackson feared that public investments offered unearned advantages to insiders that would surely lead to corruption and as he put it, “destroy the purity of our government.” He quickly stopped the practice at the federal level, cheering his supporters but dismaying promoters of turnpikes and canals.

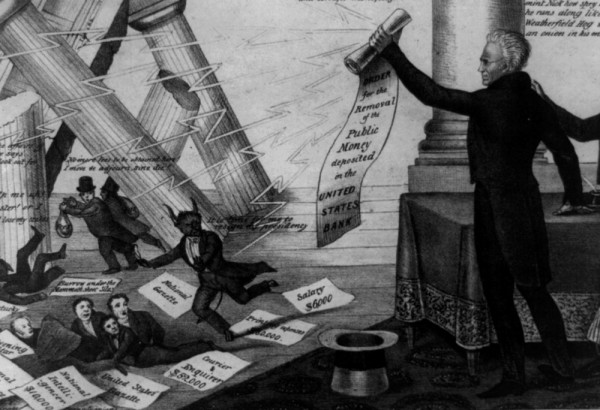

Jackson went much further in his war on the Bank of the United States. With a charter from Congress, the Bank was a public-private corporation partly funded by the taxpayers but controlled by private investors. Its hold on the nation’s currency gave it immense economic powers, but it faced no democratic oversight. Clearly foreshadowing modern controversies, Jackson was also sure the Bank made dubious loans and campaign contributions to influence politicians and editors and even to buy elections. Jackson vowed to destroy it.

When a bill to renew the Bank’s charter reached Jackson in July 1832, the president issued a slashing veto that bristled with populist attacks sounding quite familiar today. “The rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes,” he charged. They sought special favors “to make the rich richer and the potent more powerful,” rightly leading “the humbler members of society—the farmers, mechanics, and laborers … to complain of the injustice of their government.” The government should treat the rich and poor alike, but the Bank made “a wide and unnecessary departure from these just principles.” After the veto, the president withdrew the government’s money from the Bank before its old charter expired, an act his enemies condemned as a flagrant abuse of power that put the country “in the midst of a revolution.”

These moves by Jackson enraged leading businessmen, mobilized Jackson’s own Democratic Party like nothing ever had, and inspired a rival Whig party to oppose it. The parties’ ensuing clashes sent voter participation rates above 80 percent, and kept them high for decades. In his farewell address, President Jackson warned that “the agricultural, the mechanical, and the laboring classes”—populism’s “people,” in other words—“have little or no share in the direction of the great moneyed corporations,” and were always “in danger of losing their fair influence in the government.” That language is strikingly familiar to 2016 ears, as it would have been to populists in the 1890s and New Dealers in the 1930s.

Today, Andrew Jackson is no longer very popular, and many of his values are no longer ours. His vision of the “people” had no room for people of color. Some of his attacks on eastern financial elites were a continuation of the Jeffersonian attacks on urban, nationalist, Hamiltonian principles. Jackson’s populism was thus a Trojan horse for pro-slavery, pro-states rights interests. He was a wealthy slaveholder himself, with no qualms about African-American bondage and deep hostility to abolitionism. He ignored the early movement for women’s rights, and his infamous policy of Indian removal partly stemmed from demands by his “base” for plentiful free land.

Yet Jackson’s legacy is still with us, and not just the racist part. Ask Bernie, the scourge of modern Wall Street. Ask the Donald, whose promise to expel a minority group brings to mind Indian removal. As long as America venerates the Voice of the People, an evolving Jacksonian populism will survive on the left and the right.

Harry Watson teaches American history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is the author of Liberty and Power: The Politics of Jacksonian America.

He wrote this for What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian and Zócalo Public Square.

Buy the book: Skylight Books, Powell’s Books, Amazon.

*Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.