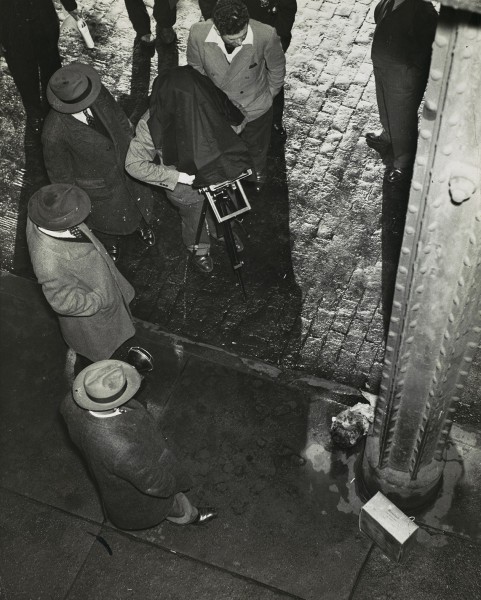

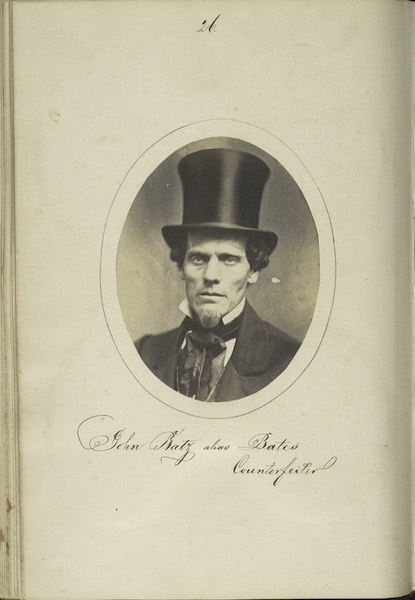

The mug shot might be a particularly clear connection between photography and law enforcement, but it’s just one example in a larger story. Since photography was born as a medium in the mid-19th century, photographs have helped to document and investigate foul play. Police and forensic investigators pour over crime-scene snaps. Journalists publish them to share the truth with readers—and sometimes to shock, astonish, or titillate. Meanwhile, those known principally as fine-art photographers—figures like Walker Evans, Richard Avedon, Helen Levitt, others—have taken inspiration from law enforcement work as well as the sometimes-shadowy worlds it pursues.

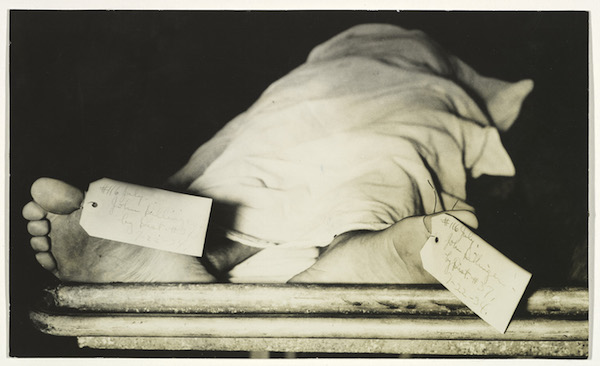

A new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, “Crime Stories,” traces these connections—from the journalistic to the artistic and from the supposedly scientific to the obviously political. The show includes a shot of the gangster John Dillinger’s feet in a Chicago morgue and a photograph of the murderer Ruth Snyder being executed by electric chair at Sing Sing. It includes an “automobile murder scene” from 1935—photographer unknown—that could be a still from an early noir.

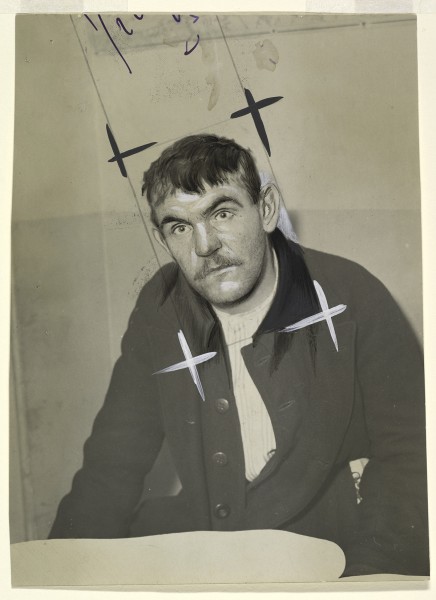

Crime pictures like these raise the stakes of an old question about objectivity. Photos seem to offer transparent access to reality—but their “reality” is partial and subject to manipulation. Bertillon’s own methods of investigation were not nearly as scrupulous as he professed them to be. Some pictures from tabloid newspapers held by the Met were “altered, painted over, cropped in different ways, in order to intensify the sensationalism,” said Mia Fineman, one of the curators who organized “Crime Stories.” As viewers, we may think that we’re savvy about such practices. Still, every photograph has a “frisson of truth to it,” which makes us want to believe in it, Fineman explained.

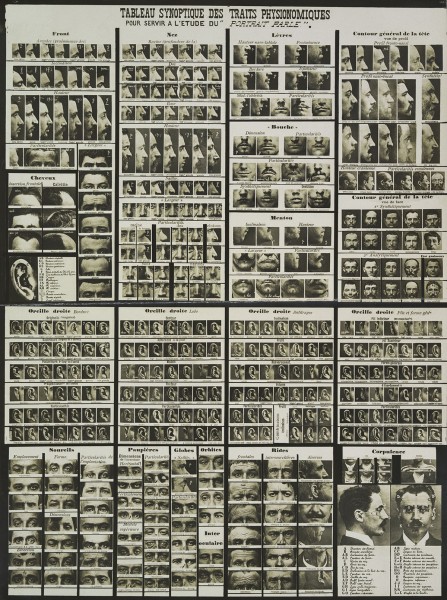

“Summary Chart of Physical Traits for the Study or the ‘Portrait Parlé,’” by Alphonse Bertillon, ca. 1909

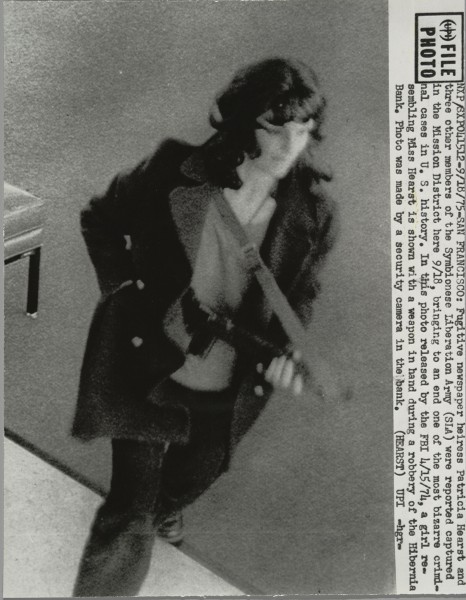

Altered images aren’t the most pernicious issue raised by the exhibition, either. It also demonstrates how photography widened and deepened ways of measuring and watching people. From the very beginning, Fineman pointed out, “photography was used as a method of social control.” It’s a short step from mug shots and crime scene photos to cameras perched in all sorts of public and private spaces. The show includes some pictures from bank surveillance cameras, including one of kidnapped heiress Patty Hearst robbing a bank. The “visual and auditory surveillance that’s become so widespread today is part of a continuum from these earlier uses of photography,” Fineman explained.

Walker Evans was one artist who understood this. Though best known for his documentary-style photographs of people suffering during the Great Depression, he also, in the 1930s, photographed anonymous people on the subway with a hidden camera under his overcoat. The resulting works, Fineman said, show how a photograph can make ordinary citizens seem suspicious or vulnerable simply by capturing them on film.

Today, the power of the photo is no longer just for law enforcement, journalists, or even professional artists. Footage from smartphone cameras has helped to demonstrate police misconduct in the deaths of Eric Garner and Walter Scott, among others. Even if, as Fineman noted, “visual evidence only goes so far in convincing people of things that they might not want to be convinced of,” photography still offers information that’s hard to dismiss. It will continue to play a part in crime stories—recording what we should know, suggesting what we want to know, and reminding us of what we never really can.

The exhibition “Crime Stories” is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York from March 7 to July 31.

This was written for Open Art, a partnership of the Getty and Zócalo Public Square.

*Photos courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

![“Lewis Powell [alias Lewis Paine or Lewis Payne],” by Alexander Gardner, 1865](http://zocalo-on.kcrw.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/2.-Lewis-Powell-alias-Lewis-Paine-or-Lewis-Payne--e1458015956474.jpg)