Recent politics is full of debates about erecting walls on the U.S.-Mexican border or barring Muslims from entering the U.S. But excluding groups of immigrants based on a particular background is nothing new—though the targets may change. It was in 1882 that Congress, for the first time in the history of the United States, passed legislation to prevent a specific ethnic group from entering the country. In effect from 1882 to 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act forbade Chinese residents from naturalizing as U.S. citizens and forbade Chinese “laborers” from entering the country at all.

The law was draconian and racist. It was also, often, ineffective. The Chinese population in the U.S. actually grew in total numbers during the census years of 1890, 1930, and 1940. Thousands of Chinese immigrants successfully challenged exclusion or tailored migration strategies to fit the demands and exploit the loopholes of exclusion laws.

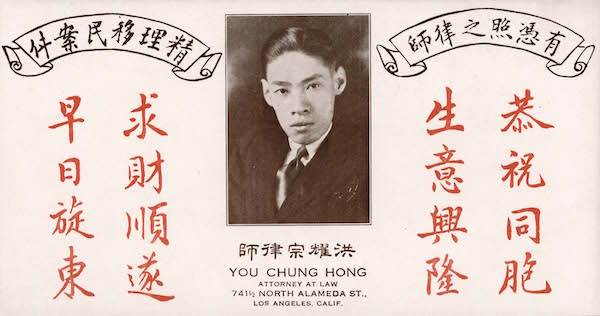

Leading this steady resistance to exclusion was Y.C. Hong, a largely unsung but important figure in the Los Angeles Chinese community. Hong was a government lobbyist, an immigration attorney who worked on at least 7,000 cases, and a leader in the larger cause of Chinese-American rights when they had very few.

Chinese immigrants started coming in large numbers in the mid-19th century when the gold rush increased the need for laborers in California. White union groups, believing that the Chinese were taking their jobs and depressing wages, stoked anti-Chinese sentiment, hysteria, and ignorance on the West Coast. Politicians got votes by denouncing Chinese people—who had very little political representation. These groups considered the Chinese immigrants too culturally foreign to assimilate. In an argument typical of the time, Congressman William Piper justified the anti-Chinese sentiment by saying, “[Chinese people] have monopolized menial labor and many of the lighter mechanic arts, thus depriving American boys and girls of opportunities of employment.” He described Chinese women as “nearly all slaves in conditions and prostitutes by vocation,” whereas the men were, according to him, “abandoned and dangerous criminals, opium smokers, and gamblers.”

Hong found his vocation because of this kind of rhetoric. Born in San Francisco in 1898, You Chung “Y.C.” Hong was the son of Chinese laborers who probably migrated to the U.S. before 1882. After serving as a translator at the Bureau of Immigration, Hong attended night classes at USC to study law. In 1923, he was one of the first Chinese-Americans to pass the California state bar. The combination of practical learning at the bureau and academic learning at USC steered his subsequent career. From a poor family, and standing just 4-feet-6-inches tall because of an injury he suffered as a baby, Hong had the strong-willed optimism that can come from overcoming adversity.

In addition to serving as president of the Chinese American Citizens Alliance, testifying before congressional committees about Chinese-American rights, and trying to sway politicians by befriending them, Hong helped immigrants fight back hard against exclusion. Some cases used a legal loophole in the Exclusion Act and subsequent legislation: Foreign-born sons and daughters of Chinese-American citizens were entitled to U.S. citizenship. As a result, Chinese immigrants challenged exclusion by claiming to be offspring of Americans. Some of them were indeed children of citizens, but others, eager to start a new life here, changed their names, identities, and family history to become “paper sons and daughters.”

Y.C. Hong with other members of the Chinese American Citizens Alliance Members, which defended Chinese-American civil rights at a time when public sentiment was overwhelmingly anti-Chinese, circa 1928.

Throughout the Chinese Exclusion years, immigration attorneys helped with these and other tactics (though Hong never knowingly promoted the use of a false identity). Since any strategy involved reams of paperwork and navigating a complicated situation in a language most of these immigrants did not understand, Hong’s services became indispensable.

Typically, a Chinese immigrant had to undergo grueling verbal interrogations and intrusive physical examinations. In 1940, Hong represented 27-year-old Wong Keen, who was asked 205 questions, including one that required him to describe his house in China down to the skylights in the bedrooms and a mill in the parlor. Of course, immigration inspectors didn’t really care about the mill in the parlor. The hearings were designed to be tedious and repetitive, with many detailed questions, so that inspectors could find inconsistencies in immigrants’ answers and deport them for lying. Dubious science could achieve the same objective. One of Hong’s clients was deported after a “study” of his bone structure determined that his age was different than the number he had provided.

All this took time and resources. Chinese immigrants typically brought very little with them on their perilous, cramped journeys in steerage aboard transpacific steamships. They had to endure waits of weeks or even months at immigration stations—San Pedro Immigration Office for L.A., Angel Island for San Francisco—until they could get their individual hearings. During that time, they were held, separate from other arrivals, in jail-like detention centers. The lucky and prepared ones could hire an immigration attorney (Hong provided an installment plan) or even give bribes. They might finally be allowed entry. Others were deported and sent back to China.

Y.C. Hong business card, circa 1928. The characters read: “These blessings I wish for my compatriots: businesses that flourish, fortunes smoothly sought, and once that is done, safe and speedy passage home.”

There were so many immigrants coming from China—and so many of them had realized that they could make legal challenges—that immigration inspectors operated with a huge backlog, and immigration laws became more stringent and complex in response to the challenges. The Bureau of Immigration was created in 1895 in large part to deal with the enforcement of Chinese Exclusion. With Chinese plaintiffs flooding federal courts, the U.S. Supreme Court in 1905 barred these courts from hearing Chinese admission cases—leaving them solely in the hands of immigration officials.

Despite the difficulty of enforcing the Act, its model of immigration exclusion based on national origin was adopted and applied to other immigrants deemed undesirable by the U.S. government (other Asians, some groups from Southern and Eastern Europe)—in continued attempts to preserve a nativist “American” identity. Legislation of this sort lasted until the repeal of Exclusion in 1943 and the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. On June 18, 2012, the U.S. House of Representatives issued a formal resolution of “regret” for the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Chinese miners work alongside miners of other ethnicities in Auburn, California, circa 1852. Fortune-seekers from around the world migrated to northern California following the discovery of gold in 1848.

Cultural effects of the Act lingered for decades. Negative stereotypes of Chinese continued to be widespread in the U.S. well into the 20th century. Many Chinese families were forced apart; others had to adopt assumed identities in order to stay in the country and even passed their assumed identities on to children and grandchildren, leaving blanks in family histories. (Some Chinese Americans trying to recover their true identities today have gone back to China to trace roots and family relations, or used the National Archives and archives at the Huntington Library—where I work—to uncover immigration history.) Professional employments outside of Chinatowns stayed closed to Chinese-Americans for a long time. And U.S. history continued to ignore the Chinese-American role in building America.

But people like Hong should be remembered—for a long, diligent record of resisting racist exclusion policies through legal and political action. This steady work now provides inspiration and example. “Those of us who have achieved acceptance through our economic or intellectual status should be the ones to lead the way in breaking down unfair barriers,” he wrote in a 1963 essay.” As long as there are some of us considered still unacceptable politically, economically, or socially, it remains a dangerous situation for all Americans, regardless of race, creed or ancestral origin. A chain is no stronger than its weakest link.”

Li Wei Yang is the curator of Pacific Rim Collections at the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. His latest exhibition, “Y.C. Hong: Advocate for Chinese-American Inclusion,” was on view at the Huntington through March 21, 2016.

He wrote this for What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian and Zócalo Public Square.

*Photos copyright The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.