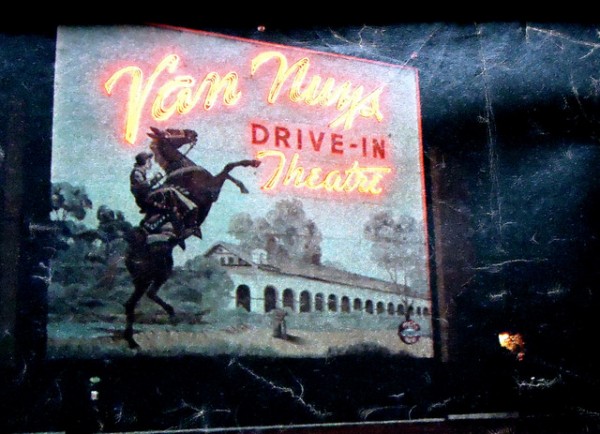

When I moved from Chicago to Studio City, California in 1992, there was only one drive-in movie theater left in the San Fernando Valley: the Van Nuys Drive-In Theatre on Roscoe Boulevard. When it opened in 1948, the backside of the Van Nuys screen had a neon mural with a bucking bronco. By the time I visited the Van Nuys, the original screen tower was gone and it had been expanded to a multiplex drive-in with three screens.

My boyfriend and I often went there to watch movies. We either sat in his Jeep or lay with blankets on the hood of my Firebird convertible. I remember it was a little run-down, and the picture was a little dark, but none of that mattered because it was really about the experience—spending time together, being outside in the great Southern California weather, watching a movie under the stars.

The Van Nuys Drive-in was demolished with little fanfare in 1998. It never occurred to me that the Van Nuys would close. It didn’t feel like the end of an era, but it was.

There were a host of drive-in closings in the late ’90s. The South Bay Six, a big six-screener at the juncture of the 405 and 110 freeways in Carson, closed in 1997. The Hi-Way 39 Drive-In in Westminster became a Wal-Mart. The Fiesta 4 in Pico Rivera, the Vermont in Gardena, the Norwalk, the Winnetka Six in Chatsworth, the Sundown in Whittier, the Anaheim Drive-in, the Azusa Foothill, Los Altos in Long Beach, and the El Monte all hung on through the late ’90s, but they were demolished one by one. Since the early 2000s, there has been only one drive-in in Los Angeles and Orange counties that has hung on: the Vineland in the City of Industry.

In their final days, these drive-ins were old and shabby looking, their marquees and murals painted over, the neon gone. The way real estate was booming in the late ’90s in Southern California, these eyesores weren’t seen as a rich piece of our cultural heritage and a way to spend good times with our friends and families—they were only seen as unused plots of land waiting to be developed. The Centinela Drive-In and Studio Drive-In were immortalized in Heat and Pee Wee’s Big Adventure, but townhouses now stand in their place.

Growing up outside of Chicago, I loved to go to the drive-in with my family in the summer. For a kid, it was a magical place with movies, a playground, popcorn, and ice cream. After many drive-ins had closed in the ’80s, I went out of my way to visit them, as if I were spending time with a dying relative. I was fascinated by the showmanship and spectacle that went into the design of old drive-ins. I wondered what their magnificent screens and marquees looked like in their heyday—and how anyone could allow them to get so run-down. That’s why I decided to make a documentary film on drive-ins. I wanted to understand why, if we still loved cars and movies, drive-ins weren’t able to survive.

At the peak of drive-in popularity in the late ’50s, the Los Angeles metropolitan area, including Orange County, was home to nearly 70 drive-ins. During the post-World War II baby boom of the late ’40s, American families were buying cars and moving to newly developed suburbs. As the freeway system grew in Southern California, the drive-in became the perfect merger of car culture and family entertainment. In the past, you got dressed up to visit a big movie palace; now, you loaded the kids into the car and headed for the drive-in for a fun night out. Later, when television became mainstream in the ’60s and ’70s, families stayed home and drive-ins became teen hangouts.

Los Angeles is a city with perfect weather, a car culture, and a love of movies. You would think: If drive-ins could survive anywhere, certainly it would be here! So what happened?

A perfect storm of social, economic, and other factors made drive-ins hugely popular and, about 40 years later, led to their decline. As suburbs continued to expand in the ’80s, drive-ins that were once on the outskirts of town ended up being closer to inner cities where there was more violence and gang activity. Teens started flocking to the mall to wander around and hang out—where multiplex theaters with surround sound were increasingly being built. Film distribution also changed so that B movies went straight to cable or direct-to-video, where they could be watched from home. Video games, in arcades or played on systems like Atari, created a new diversion and drew people away from drive-ins. Finally, as real estate values rose in Southern California, old, poorly maintained drive-ins were demolished.

But something interesting has started to happen. Across the country, people are remembering how fun it was to go to the drive-in and realizing what we’ve lost. Since the year 2000, at least 30 old drive-ins have re-opened in the U.S., and at least 35 new ones have been built. There were five more new drive-ins opened up in 2014.

Sometimes these drive-ins are built on new land, on the outskirts of a town just like the original drive-ins. But in many cases, drive-in owners are looking for what they call a “footprint”—a plot of land that used to be a drive-in and still has the zoning and layout of a drive-in. Maybe it still has the grading and the ramps. Maybe it still has a ticket booth, or a snack bar standing, or in some cases even a screen.

I know the people of Los Angeles have been hungry for the outdoor movie experience. The Cinespia screenings at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery are always packed. The Electric Dusk Drive-in—a blow-up screen on a rooftop in downtown Los Angeles—is also thriving. The handful of drive-ins that stayed open in Southern California, like the Vineland, are well-attended. A little further east, you’ll find other survivors—the amazing Mission Tiki Drive-In in Montclair and two in Riverside: the Van Buren and the Rubidoux.

The Santa Barbara Drive-In in Goleta reopened in 2012 after being dark for nearly 20 years. And we have many drive-in footprints in Southern California, including the Roadium Drive-In in Torrance, the Santa Fe Springs Drive-In off the 5 Freeway, the Starlite in South El Monte, and the Paramount. All of these operate only as swap meets today, but the Paramount Twin Drive-in will be re-opening as a drive-in later this spring thanks to the son and grandson of the man who originally built it.

Could it be that L.A. is catching on to the drive-in revival? I went down to the Paramount to check it out. Although the space was filled with tables of people selling blankets, shoes, and knick-knacks, I saw that the ticket booths have been built. Poles are already in the ground where the new screens will be constructed. And they have space for more than 800 cars.

April Wright is the director of Going Attractions: The Definitive Story of the American Drive-in Movie.

This was originally published by Zócalo Public Square on March 12, 2014.

*Photo courtesy of Cinema Treasures.