Ever since the brutal mass shooting at a gay nightclub in Orlando in the early morning hours on June 12, Florida has become the focus of nationwide concerns about easy access to guns, and the mayhem such access can produce.

That focus on the Sunshine State is even more appropriate than the American public understands. The state of Florida has long played a leading role in the establishment and expansion of the right to bear arms.

As constitutional rights go, the right to bear arms is of relatively recent vintage. In 1991, then-retired Chief Justice Warren Burger characterized the notion that the Second Amendment protects such a right as one of the greatest frauds perpetrated on the American public in his lifetime. In Burger’s view, and in the uniform view of the federal courts for more than 100 years, the Second Amendment protected only the states’ prerogative to have militias. It afforded individuals no personal rights to own or carry firearms.

But In 2008, the Supreme Court ruled in District of Columbia v. Heller that the Second Amendment did in fact protect such an individual right to bear arms. How did this change happen? And what does it teach us about how constitutional law develops in the United States?

The place to start looking for an answer is not in Washington D.C—but in Florida. And specifically, in the offices of Marion Hammer, a 4’11” grandmother, now in her 70s, who never went to law school but happens to be the most powerful lobbyist in Florida.

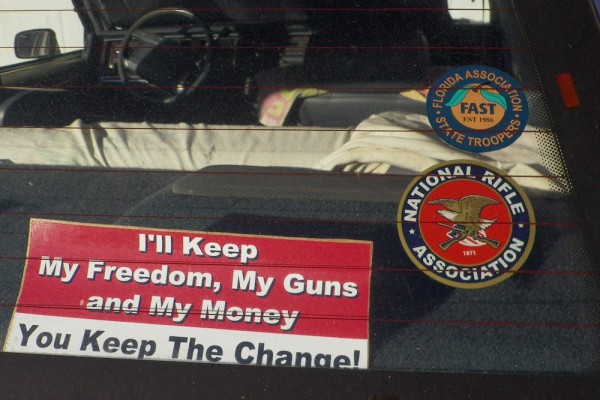

Hammer was the first female president of the National Rifle Association. And it is the NRA that is responsible for realizing and protecting the contemporary right to bear arms. Hammer’s strategy in Florida has been key to the NRA’s national success.

Marion Hammer, left, former President of the National Rifleman’s Association, speaks to the House Judiciary committee about the firearms/motor vehicles bill, Tuesday, April 4, 2006, in Tallahassee, Fla.

The NRA itself was primarily a marksmanship, hunting, and sport shooting organization for most of its history. It did not even establish a political arm until 1975, around the same time Hammer became involved in the political fight for gun rights. Both developments were a response to the first major piece of federal gun legislation, the Gun Control Act, passed in 1968 after the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. Hammer and the NRA saw the Gun Control Act as a threat to their liberty, but understood that the federal courts would not be receptive to a constitutional challenge, given their longstanding rejection of an individual right. All precedent stood against them. Instead, the NRA looked to alternative, more sympathetic forums. It found them in the states, where gun control advocates were not organized, and where politicians responsive to rural constituents were especially receptive to the need for individuals to own guns for self-defense. In no small part because of Hammer’s early and effective advocacy, Florida became the NRA’s go-to state, so much so that it is sometimes called the “Gunshine State.”

In the 1970s, the NRA launched a state-by-state strategy to establish gun rights. Under Hammer’s direction, it started in its most hospitable state, and then exported victories won there to other states. In Florida and other states, NRA lobbyists fought for amendments to state constitutions to recognize an individual right to bear arms. They pressed for laws requiring state and local governments to issue individual licenses for concealed weapons, so long as applicants were not disqualified for specific reasons, such as felony convictions or mental illness. They successfully protected gun manufacturers from liability for injuries caused by illegal use of their weapons. These legislative victories—exported one state at a time—created a new environment. By 2008, when the Supreme Court in Heller took up the question of a federal right to bear arms, the vast majority of states already protected individual gun ownership rights, thereby easing the way to recognition of a federal right.

The NRA worked in other venues as well to buttress its view of the Second Amendment. It supported scholars who argued that the Second Amendment was originally intended to protect an individual right, and in doing so, reversed settled wisdom in the legal academy. Before the NRA got involved, virtually all law review articles advanced the “state militia prerogative” view of the Second Amendment. By the time the Supreme Court took up the question in 2008, the majority of law review articles supported an individual rights view, and several well-known liberal constitutional scholars, including Harvard’s Laurence Tribe and Yale’s Akhil Amar, had given that view credence.

In 2000, after throwing its substantial political muscle behind the election of George W. Bush, the NRA convinced Attorney General John Ashcroft, an NRA member, to reverse the Justice Department’s longstanding position on the Second Amendment. In response to a letter from the NRA, Ashcroft took the position, for the first time in Justice Department history, that the Second Amendment protected an individual right. By 2008, again at the NRA’s urging, Congress had also adopted that view, in two gun rights laws. Thus, by the time the Supreme Court took up the issue in 2008, the NRA had shifted the ground on this question in its favor in the states, the legal academy, the executive branch, and Congress. The Court’s decision was simply the final shoe to drop.

As this account suggests, recognition of an individual right to bear arms was not imposed from the top down by five justices, but developed from the bottom up, through decades of advocacy and debate sponsored by the NRA. And even after receiving the Supreme Court’s imprimatur, the right is more vigorously protected by the NRA than the federal courts. Through its political influence in Washington and the states, the NRA can block laws that would otherwise be sustained by the courts, such as the effort to require universal background checks for private gun purchases after the Sandy Hook Elementary School mass shooting. And the NRA has repeatedly succeeded in obtaining gun protections through state law that the Second Amendment does not require, such as the right to carry concealed weapons in public. Marion Hammer and her colleagues at the NRA remain the most significant guardians of the right to bear arms, notwithstanding the right’s formal recognition in our constitutional law.

This story is not unique to the NRA and the Second Amendment. Often, the key actors in constitutional law are not the justices on the Supreme Court, but “we the people,” acting in associations of like-minded citizens, and engaged in advocacy far beyond the federal courts. Similar organizational campaigns transformed federal marriage equality from unthinkable to inevitable, and forced President George W. Bush to curtail many of his most aggressive counterterrorism measures by the time he left office in 2009. As Learned Hand, a legendary federal judge, once said, “Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women. When it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it … while it lies there it needs no constitution, no law, no court to save it.” Civil society organizations—on the left and the right, whether they are the ACLU or the NRA—help to ensure that liberty lies in our hearts, and is reflected in our constitutional law.

David Cole is the Hon. George J. Mitchell Professor in Law and Public Policy at Georgetown Law, and author of Engines of Liberty: The Power of Citizen Activists to Make Constitutional Law.

Buy the Book: Skylight Books, Powell’s Books, Amazon.

*Lead photo courtesy of Daniel Oines/Flickr. Interior photo by Phil Coale/Associated Press.