If Robert Mapplethorpe popularized photography as a fine art form, his longtime partner Samuel J. Wagstaff Jr. gave it legitimacy. The former curator of the Wadsworth Athenaeum and the Detroit Institute of Art, Wagstaff started seriously collecting photographs in the early 1970s, around the same time he and Mapplethorpe began a romantic relationship. The pair were a fixture on the downtown New York art scene, and their joint promotion of photography soon piqued the interest of major gallerists and critics.

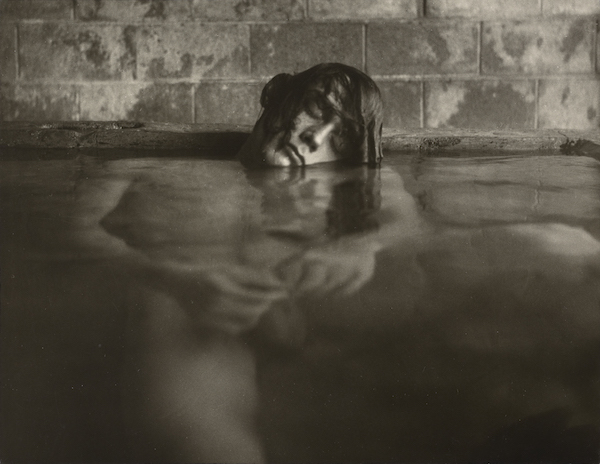

While Mapplethorpe perfected his iconic style, the independently wealthy Wagstaff made a name for himself as a voracious collector. Wagstaff chased photographs back to the form’s beginnings, collecting images created as early as the 1830s, some of which he picked up from thrift shops and flea markets. He championed the work of little-known 19th century photographers like Gustave Le Gray, whom he compared to Rembrandt, and Julia Margaret Cameron, later renowned for her soft-focus portraiture. He also added contemporary photographers like Jo Ann Callis and Edmund Teske, as well as anonymous works, to his collection. “This is the man who set the aesthetic benchmarks for what’s good in photography,” art historian Clark Worswick told The New York Times’ Philip Gefter, who later wrote Wagstaff’s biography. Reviewing a 1978 exhibition drawn from Wagstaff’s burgeoning trove of photographs, a Washington Post critic declared, “Sam Wagstaff is the artist that one most remembers after looking at this show.”

In just a decade, Wagstaff amassed one of the world’s most significant collections of photography. In 1984, the J. Paul Getty Museum acquired his more than 25,000 images as a founding pillar of their Department of Photography. Three years later, Wagstaff died from AIDS-related pneumonia.

To accompany their major retrospective “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium,” the Getty is presenting “The Thrill of the Chase: The Wagstaff Collection of Photographs.” This three-gallery exhibition contains 101 works—both recognizable masterpieces and less well-known selections—that highlight Wagstaff’s passionate pursuit of fine art photography.

“Wagstaff was attracted to photographs that had the power to get his imagination going,” said exhibition curator Paul Martineau in a recent interview. In reflecting on what set Wagstaff’s collecting apart, Martineau quoted Wagstaff himself: “‘Beauty can be found in truth, or better still, in unexpected places.’”

*In the order of the gallery, images courtesy of:

1. Dali Atomicus, 1948, Philippe Halsman. © Halsman Archive. Courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

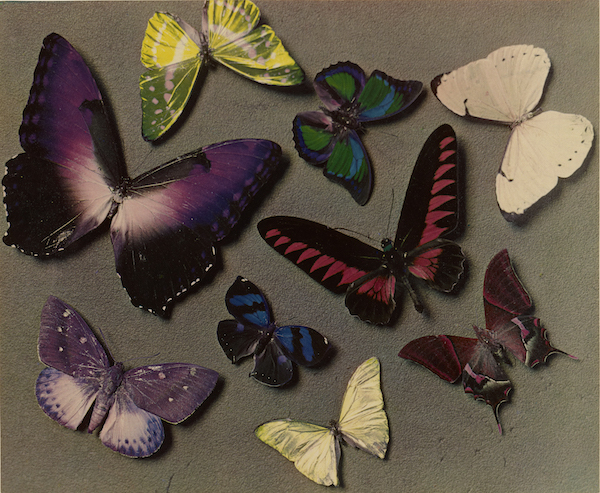

2. Butterflies, 1935, Man Ray, © Man Ray Trust ARS-ADAGP. Courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

3. Running Legs, Forty-second Street, New York, 1940-1941, Lisette Model. © Estate of Lisette Model, courtesy Baudoin Lebon/Keitelman. Courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

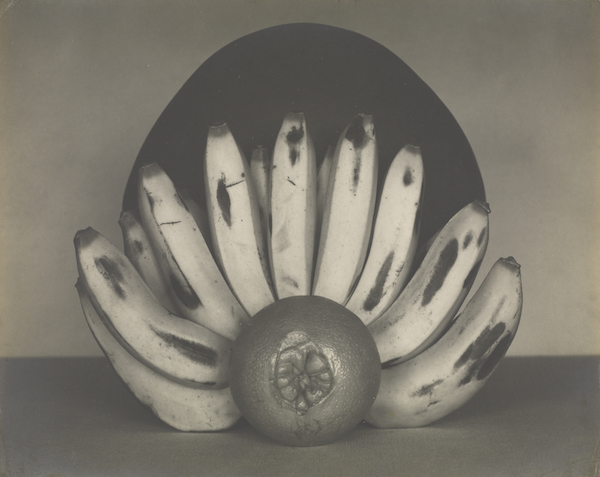

4. Bananas and Orange, April 1927, Edward Weston. © 1981 Arizona Board of Regents, Center for Creative Photography. Courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

5. Mineral Baths, Big Sur, California, 1967, Edmund Teske. © Edmund Teske Archives/Laurence Bump and Nils Vidstrand, 2001. Courtesy of J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

This essay is part of What Did Robert Mapplethorpe Teach Us?, a special package of stories from Zócalo Public Square.