Growing up in Philadelphia, I played and photographed in the ruins of buildings—some noble, even ones designated as important national historic landmarks. I wasn’t really cognizant of their importance in history then, but our surroundings have a way of impressing themselves upon our hearts.

As I grew up, like most Philadelphians, I accepted as normal the run-down condition of my city, a once burgeoning industrial metropolis exploding with promise. The boom years, between the Civil War and World War II, define most of Philadelphia architecturally. Solidly constructed, the edifices erected in this period projected a bright optimism of a maturing civilization, a creative urbanity that played a role in shaping the nation culturally and intellectually.

It took a period of exposure to Europe in 1990, while working as a roadie on a 50-city tour with the punk band Shudder to Think, to open my eyes to the real tragedy of Philadelphia’s chronic 20th-century decline. In Europe you can feel the pride and dignity expressed in the preserved architectural history. It was a revelation to see that previous heydays can be preserved, can remain clearly legible, still thought-provoking and energizing. In Europe I came into contact with not only marvelous buildings saved by the prevailing culture but also historic buildings being saved and renewed by youth subculture.

Most impressive to me was the Reitschule, a massive old riding academy built in 1897 in central Bern, Switzerland. Its provocative late Victorian style reminded me of home. This once vacant hulk was taken over by youths in the 1980s, who transformed the 19th-century complex into an autonomous culture center providing a bevy of cultural and human services—theaters, large-scale sculpture, music, nightlife, housing, printing, darkroom, café, meeting center, you name it. All arranged through a consensus building procedure traditionally understood as anarchy. I found that punk can be viewed as a bulwark movement against commercialism in defense of culture.

Returning to Philadelphia in 1991, I felt a mounting sense of mourning and frustration at the desperate state of so many historic buildings across the city. Pride of place has always been something I’ve shared with my fellow Philadelphians, but it became mingled with a sense of shame at the realization that America’s fatalism in the face of urban decay was an aberration among prosperous nations. The great architectural dilemma of our times is the impossibility of assessing civic value in business terms. There is no bottom line assigned to real estate’s civic, social, and historic worth.

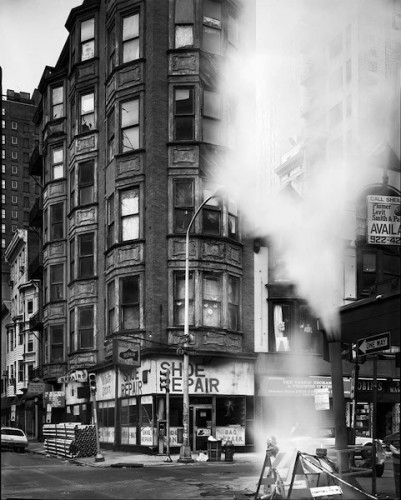

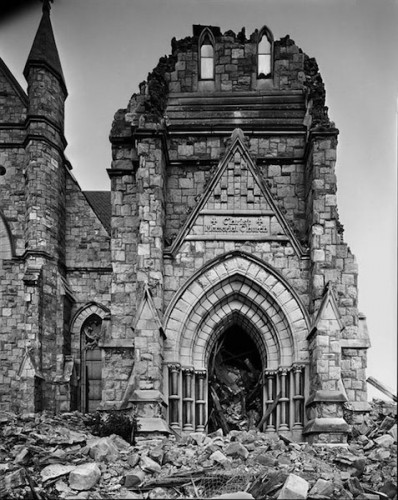

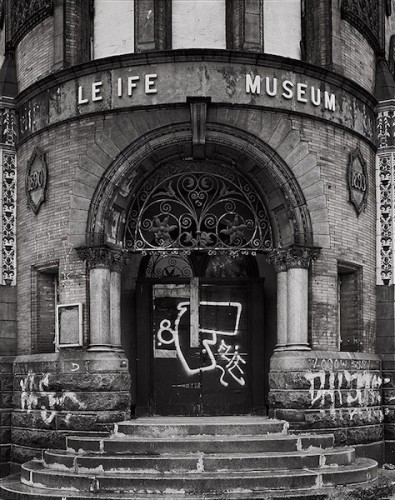

In the early ‘90s I set out to photograph Philadelphia’s buildings as an exercise in understanding this chronic decline and its impact on our shared heritage. At that time, the plague of neglect was beginning to consume Center City, the third largest downtown in the country. My framing of subjects was in a portrait style and I aimed to capture a sense of interiority, allowing stones to speak. Most of the buildings I managed to capture were caught at a pivotal point. One could still clearly see the promise they once expressed, and the possibility of rekindling it.

In my 2014 book of these photographs, City Abandoned, Charting the Loss of Civic Institutions in Philadelphia, I collected stories that leant testimony to my subject’s history and plight. More than a third of the 92 public buildings in the book have been demolished. Almost half have found a new purpose. The rest remain vacant and in limbo.

The individual portraits add up to a collective failure of historic stewardship. Our city’s leadership has been burdened and its pride beaten down by decades of urban neglect and racial segregation. In the second half of the 20th century, when city cores across the country were being hollowed out, Philadelphia’s leaders feared they could not place any obstacles in the way of business development. Because of this legacy, Philadelphia, for all intents and purposes, continues to be without a functioning historic preservation code. The one in effect today has been crafted like Swiss cheese, notable mostly for its gaps. The city has neglected to survey and designate hundreds of historic landmarks from its more than two centuries of progress. Even when a building is fortunate to be recognized by a designation, it is no guarantee of survival.

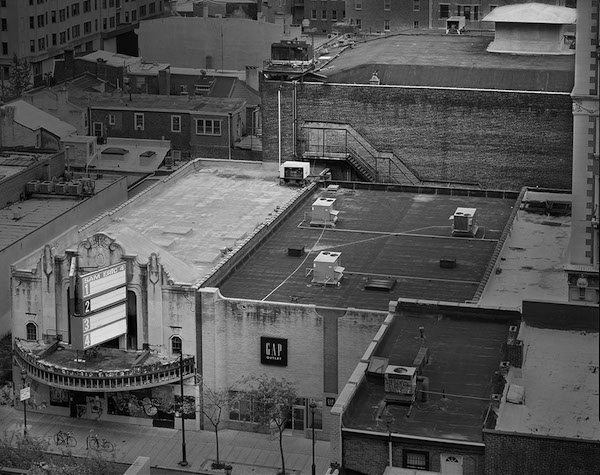

The case of the Boyd Theater is a recent and salient example. Philadelphia’s last art deco movie palace in a city that once hosted dozens, the Boyd was a designated historic landmark. When owners threatened to demolish it, the public staged numerous protests and flooded every public hearing in defense of this important architectural masterpiece. The battle continued for years with a succession of determined owners. But in the end the city and the state did not rise to the theater’s defense as lawyers argued it had no potential for reuse—though many other American cities have preserved art deco theaters as public-private ventures. The theater was demolished last year.

Buildings, particularly historic ones, can form profound emotive connections. They represent perhaps our closest and most meaningful bond to the material world. These are shared connections for family, neighbors, and community. When the Sears, Roebuck Co. Clock Tower was imploded in Northeast Philadelphia in 1994, tears were shed by hundreds, as if a loved one had just died. People rushed the site to claim souvenirs once the smoke and dust had cleared, trying to retain a piece of the monument and what it had symbolized in their lives and for the neighborhood. This officially undesignated but universally recognized landmark was now groomed for a new strip mall development contributing to the geography of nowhere.

Regardless, Philadelphians have remained proud of this town and that pride is growing as it draws fresh recruits. The high water mark of urban decline was reached in the mid-1990s. Turnaround was in the air in the early 2000s, when savvy developers like Tony Goldman—who had helped breathe life back into SoHo in Manhattan and Miami’s South Beach—staked out his claim in one of the more badly deteriorated sections of Center City, 13th Street. Goldman was one of those rare developers who could identify walkable, architecturally rich districts that were undervalued and plagued by poor quality of life.

This summer, local developer Eric Blumenfeld, a disciple of Goldman, is unveiling one of the more remarkable architectural comebacks: the Divine Lorraine, a former 1894 luxury apartment house which became one of the earliest integrated first-class hotels in the nation in 1948. This distinct landmark has finally been renovated with apartments and retail, after sitting vacant for some 16 years after a stint as the home to Father Divine’s International Peace Mission Movement.

Thirteenth Street was the first area in the city to go from tenderloin to très chic, with boutiques and some of the city’s most popular restaurants and bars. North Broad Street is clearly next with the opening of the Divine Lorraine. Philadelphia`s popularity has surged in the past 15 years, to an almost unfathomable degree to long-time residents. It is partly this city’s charm and status as a birthplace to our republic that draws newcomers here. But it is more than that.

Despite the ravages it has withstood, Philadelphia continues to pull in more and more people who crave the feeling of being somewhere authentic. Somewhere with a memory.

In “Beyond the Circus,” writers take us off the 2016 campaign trail and give us glimpses of this election season’s politically important places.

Vincent D. Feldman is a photographer, teacher, and lecturer based in Philadelphia and Tokyo. He is currently working on a portfolio of photography tracing the evolution of Western architecture in Tokyo from Meiji through to the contemporary period. His work can be found at www.vincentfeldman.com.

*Photos by Vincent D. Feldman.