“So what’s the secret, Max?”

“I guess you’ve just gotta find something you love to do and then … do it for the rest of your life. For me, it’s going to Rushmore.”

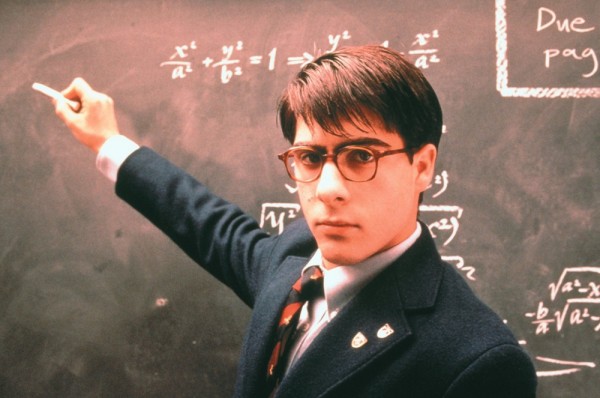

Rushmore is a movie crammed with many great moments, but this exchange between the middle-aged business tycoon Herman Blume (Bill Murray) and the precocious Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman) establishes the emotional connection around which the darkly inspiring comedy revolves.

I remember being transfixed by Wes Anderson’s film when I first saw it in a theatre in early 1999, and have found it equally rewarding in the dozen or so times I have watched it since. Rushmore manages to be funny, wistful, smart, dark, poignant, and irreverent without ever being cynical—a rare feat in our culture.

Still, some people through the years have looked at me askance when I pronounce Rushmore, without hesitation, as my favorite movie. You know, that look that asks, “What does that say about you?” I don’t imagine Rushmore is on the list of movies political consultants advise clients to mention as their favorite movies.

So what does it say about me? The question makes me uncomfortable, to the point where I start wishing I could change my answer to Casablanca or Star Wars. Or maybe I could simply deflect, by asking, as Max does in an early scene with his headmaster Dr. Guggenheim, “Couldn’t we just let me float by? For old time’s sake?”

During my most recent viewing of Rushmore, I was struck (probably because I was sharing it with my son for the first time) at how painfully awkward and unsettling some scenes can be. You wince, or want to look away, when the 15-year-old Max is putting the moves on Rosemary Cross, the school’s beautiful first grade teacher, an English widow whose husband had attended the school. Or when he holds an unauthorized ribbon-cutting ceremony for an unauthorized aquarium he wants to build in her honor. Or when he insults Cross’s date to the play he’s put on, or lies to Blume about his father, a barber, being a brain surgeon.

Max is a kid from the wrong side of the tracks who lost his mom when he was too young. But he got a scholarship to the rich kids’ school because he wrote a “little one-act play” about Watergate in the second grade that convinced his mom, shortly before she passed away, that her son should attend Rushmore Academy. Now Max is on the verge of flunking out—not because he is uninterested in school, but rather because he is the school’s heart and soul, the epicenter of every extracurricular imaginable, with little time for his studies.

High school movies will always be a cinematic gold mine because those teenage years are such a wrenching wasteland—an exile from both childhood and adulthood—to which everyone can relate. What differentiates Rushmore is how the Max-Blume-Cross relationship transcends generations. Even excellent high school movies that capture the intricacies of teenage culture can struggle to establish any nuanced relationship between the teenagers and the rest of society. Adults often come across as stick figures, lacking in understanding. The conceit is that we adults in the audience have a better connection with the on-screen teenagers than the on-screen adults do.

Despite being named after the school, Rushmore breaks these teenagers out of their cage and connects them to the rest of us. Bill Murray as Blume, a rich businessman trapped in a soulless life, gets a kick out of Fischer from their very first encounter, no doubt envying the teenager’s idealism, enthusiasm, and even his nerdy goofiness. Blume sees some of his eroded self there, and wants some of that spark. It’s the adult asking the kid, after all, what’s the secret to life, not the other way around. Meanwhile Max admires Blume’s independence. And they both see in Cross the possibility of redemption, by saving her from her sadness. These are all estranged characters, exiles who recognize each other as such and embrace their unexpected bond.

Even among the adults, the irrepressible Max takes the lead. Blume arrives at Cross’s doorstep in one brilliantly understated scene to awkwardly admit that he can’t remember whether Max had organized anything for them that day. And in what’s probably my favorite scene of all (that is a tough, shifting, call), Max asks to speak to his new classmates at Grover Cleveland High, the public school to which he is exiled upon expulsion from Rushmore, and tells them that he looks forward to contributing to the school, noting that he is aware it doesn’t have a fencing team, but that he will work on it. Another exile in her own right, Margaret Yang, comes up to him after class to say, “I liked your speech.” And, more to the point, “I don’t think I’ve heard of anyone ever asking to give a speech in class before.”

We can all relate to some threads in Rushmore. I came to the United States from Mexico to go to a prestigious boarding school when I was Max’s age, and struggled at first to adapt to a new culture, and new expectations. I was always eager to grow up, to move on, which invariably meant having some crushes on inappropriately older women. Most of us don’t act on these impulses, but the yearning is clearly there, to be identified with by people you admire, who aren’t necessarily your age. In middle school I had a younger friend, a guy two grades below me, because he happened to be the only other kid in our school rooting for the same professional soccer team I did. Age, as Rushmore makes clear, shouldn’t be the only basis for a bond, for identifying ourselves in another.

The director, Wes Anderson, takes us on quite a ride (I am not as enthusiastic about his subsequent movies, in which he at times succumbs to his gift for set pieces at the expense of fluid storytelling)—an often uncomfortable ride, like teenage-hood itself, but one that ends in redemption. In his own neurotic, but ultimately generous, way, Max makes things right for all around him.

As Ms. Cross, impressed, tells him: “Well, you pulled it off.”

“It went ok. At least nobody got hurt,” Max responds.

“Except for you.”

“Nah, I didn’t get hurt that bad.”

But some. That’s what being an exile from both childhood and adulthood is all about.

Andrés Martinez writes the Trade Winds column for Zócalo Public Square, where he is the executive editor. He is also a professor at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.

*Photo courtesy of Touchstone Pictures.