You could say that walking runs in my blood: I can’t remember a time when I didn’t take long walks with my dad, though why was a mystery. Recently, I’ve been working to restore and build a trail in Apple Valley that will allow everyone to walk from the flats of downtown up to the cool, beautiful peak above the town.

I was born in Irvine and moved to Apple Valley in the High Desert of the Inland Empire in the year 2000, when I was two. My dad was working for CalTrans and my mother was a stay-at-home-mom for a year, and later on she became the Director of Patient Access at St. Mary Medical Center. They wanted to live in a place that was safe to raise a family, with fresh air, and lots of room for my dad to walk.

While it’s true that the air is fresher in the high desert, that doesn’t always mean people are healthier. A recent study found that 71 percent of adults and 31 percent of children in the high desert are overweight or obese, and San Bernardino County as a whole ranks as one of the most overweight counties in the country. Our rates of heart disease and diabetes are among the highest in California. More than two-thirds of children don’t meet basic fitness standards.

Fortunately for me, my parents always encouraged me to be active as a child—from little league soccer, to daily walks. When I was little my father would take my hand and we would walk and walk and walk. It never occurred to me to question all of my father’s walking—I never asked. But a couple of years ago, when he felt I was old enough to understand, he told me why.

In 1978 my dad fled his native Ethiopia during Qey Shibir, the Red Terror that mounted during Mengistu Mariam’s brutal communist takeover of the country. Fled isn’t the right word, exactly. He walked. He was 20—just a couple of years older than I am now—and a college student at the time, but my grandfather arranged for him and one of his brothers to escape with a group disguised as merchants, guided by a star-reading shaman.

My last name, Gessesse, comes from a long line of religious warriors—kings and queens defending the faith, fighting for the spirituality of Ethiopia. It was one of the earliest countries to embrace Christianity. But my grandfather could see that this was not the time to fight. It was the time to walk away. And so he sent my father and my uncle and the shaman and the rest of the group into the Ogaden Desert, and they walked, for two and half months, until they reached Djibouti.

My dad was able to make it to the U.S., win political asylum, and put his life together in America. He and my mom knew each other in Ethiopia—she is half Greek and had a Greek passport so she was able to get out on her own—and they reunited in the U.S., got married and made a life for themselves in California.

In this new life, my father kept walking. He walked, of course, to stay healthy. But also, I think, to remember that long desert journey, feeling heartbroken to leave, but grateful to survive when family and friends were dying, horribly, at the hands of the new regime, not knowing if at any moment they would be found out and punished or killed.

As early as I can remember—long before I learned the painful details of my father’s life-changing journey—my parents, especially my mother, taught me about love and generosity and helping the community. For the people who live in the high desert, life can be hard. Some people don’t have enough money to buy food. Or they may have grocery money but no car, no way to get to the market.

Every weekend when I was little we joined a group that would make care packages for the hungry and the homeless people who lived in our community. We would meet them at the local park and talk with them and give them lunch. Not like, “here take this food and go away,” but like “hi, how are you, what’s going on with you today?” When I was very small I remember trying to get them to come join me on the swings. Sometimes they would.

As a kid I struggled sometimes to fit in. I was Ethiopian, but “only” half, so not truly habesha. I wasn’t white either. I struggled with the image of the white, skinny ideal, with long, straight hair and blue eyes. I’m melanin-blessed. I have a bigger bottom and a small chest and curly, frizzy hair. My mother taught me to appreciate myself and see my self-worth and self-value. I struggled to strike a balance between a face at home, and a face at school. Volunteering—community service—was an environment that fostered a safe space. I loved it, I felt a purpose, and I felt appreciated, not judged.

Fast-forward to me as a high school student, outgoing and restless. I was such a “do-gooder” that my friends would sometimes laugh at me, but then I would say, come along and see for yourself, and many times they would wind up joining me. Everyone knew about me, and so a teacher told me about the Apple Valley Legacy Trail and how a small group was trying to save it.

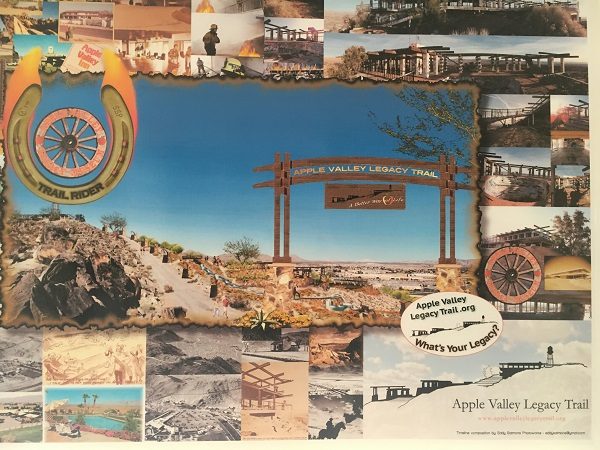

The trail runs through the center of town and leads right up one of the highest points in Apple Valley. But it wasn’t what I’d really call a “trail.” I’m a runner, and the path is near my house, so I’d explored it on my runs. It was overgrown, covered in trash and graffiti. It was so neglected most people my age didn’t even know it existed. Which was a shame, because even with all the mess, I felt it was a spiritual place. Up there you cannot hear a car horn and there are no billboards in sight. The view is beautiful, the air is fresh, and it’s free to anyone who wants to go.

Sometimes Apple Valley has a reputation, either as very boring because we are so far from the city, or very bad, because people hear about the part of town near the trails called “felony flats.” But this was a chance to clean up blight, to change people’s perceptions by creating something special that you could only find here.

My mind was in full motion: a local project that needed help, to restore something beautiful, that would get people outside and bring them together. What could be better? There’s a historic house there, the Hilltop House, which was privately owned, and a bunch of volunteers worked very hard to raise the money to get the city to buy the house to turn it into a museum.

I got together with some of my classmates and we sacrificed sleep and some study time and organized an old-fashioned steak fry, in conjunction to the Hilltop Legacy Project Team/Town Council to help with the fundraising. We got dressed up in old-timey costumes and decorated with hay bales to give the night a vintage feel. People loved it.

There’s a lot of community support for the trail and it’s working its way through the city approval process. I spoke before the city council to explain why this trail is so important. Sometimes I go up there and just imagine what it’s going to be like, a smooth, easy trail that kids can run up and down, that will become such a part of the life here that everyone will know about it and use it.

This fall I started college, away from home for the first time. I imagine how one of these days, once the trail is ready, my mother and father will walk out of our front door, and up the trail. They will stand at the top and see the all of the valley, with a feeling of nostalgia, but this time, with pride and hope as a reminder of their new beginning.

Alexandra Gessesse is a freshman at UC Santa Barbara.

This essay is part of a Zócalo Inquiry into what makes a healthy neighborhood, produced in conjunction with the California Wellness Foundation’s Advancing Wellness Poll.

*Lead photo: Alexandra Gessesse with her parents in Apple Valley. Lead photo and last two interior photos by Sara Catania.