In August 1946, a year after Japan surrendered, a musical entitled “Hawaii no Hana” (“Hawaiian Flower”) opened at the Nichigeki Theater in Tokyo’s Ginza district. The city had barely started to recover from the devastation of the war, and a good portion was still in ruins. The Nichigeki hadn’t been damaged in any of the American air raids, but it was in bad shape. Before the war it was Tokyo’s most lavish entertainment venue, but now it was falling apart from neglect, with most of the seats missing. Patrons had to stand.

“Hawaii no Hana” starred Katsuhiko Haida and Hideko Takamine as Hawaiian royalty who had been promised to each other in marriage as children. She flees the island before the wedding and doesn’t return until years later. Then she falls in love with a man she believes is a commoner, but it turns out he’s really the prince who was once betrothed to her. They live happily ever after.

Exhausted by the war and living under U.S. occupation, the people in the audience were unsure of their future, and “Hawaii no Hana” offered escape and a small measure of assurance that things might be better. But what really made the musical a huge hit was the aura of Hawaii. Takamine, a major movie star at the time, danced the hula. Haida, along with his brother, Haruhiko, and the Moana Glee Club, were popular acts in Hawaii, making records that sold in Japan, including a Japanese language rendition of Rodgers and Hart’s “Blue Moon.” They had their own radio show, and during the ’30s all of Japan’s major cities had dance halls that played Hawaiian music. Japanese people had been migrating to the islands since the late 19th century to work on plantations, forming their own communities in the process. But during the war, all Hawaiian music was banned in Japan since Hawaii was a territory of the enemy.

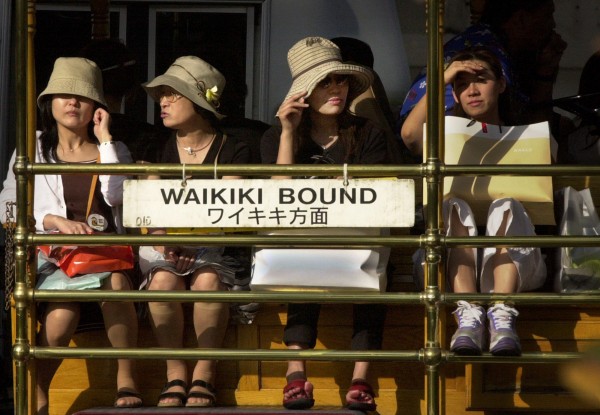

When Americans juxtapose Japan and Hawaii in the same thought, most likely they think of Pearl Harbor, a place that has no real purchase on the Japanese imagination since the associated destruction is so completely alien to their conception of Hawaii as land of carefree recreation. In fact, many younger Japanese, even if they know about the sneak attack, probably don’t know that Pearl Harbor is in Hawaii. The USS Arizona Memorial is not something that’s usually mentioned in sightseeing brochures or on TV travelogues in Japan.

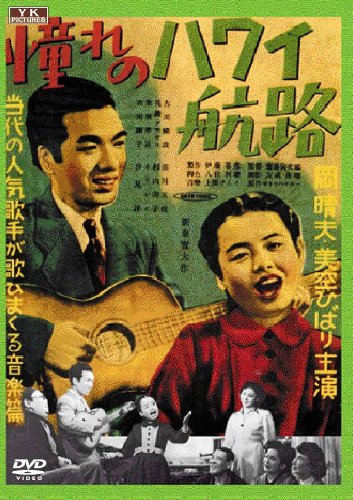

Even the people who attended “Hawaii no Hana” didn’t think about Pearl Harbor. They wanted to forget all that. The musical helped jump-start postwar Japanese popular music, according to Yujin Yaguchi, a University of Tokyo professor, who wrote the book, Akogare no Hawaii (Longing for Hawaii). Two years later, in 1947, singer Haruo Oka had a smash hit with the song, “Akogare no Hawaii Koro” (“The Hawaii Route I Long For”), a jaunty tune about a fictional cruise ship that went from Japan to the Pacific islands. The song contained no Hawaiian music elements, but the lyrics about an exotic land far from everyday cares made a distinct impression.

Singers of Akogare no Hawaii Kōro.

Hawaii’s tropical charms were thoroughly imprinted in the nation’s consciousness, but almost no one living in Japan at the time had ever actually been to Hawaii. Even after the occupation ended in 1952, Japanese people were effectively banned from going overseas due to currency exchange laws. Even if they could afford to travel, and very few people could, they were limited by how much money they could take out of the country.

Hawaii-related entertainment of those years imparted how unattainable the islands were as a travel destination. “Akogare” implied a place you will probably never visit, and the movie adaptation of the song, starring superstar child actor Hibari Misora, was not filmed on location but rather in Japan. The shots of Hawaai’s Diamond Head and the beaches of Honolulu were derived from stock footage. The thing you can’t have becomes all the more desirable and during the 1950s Hawaii retained an image that transcended the usual trappings of a vacation resort. In a country that was rushing headlong into a loud, gray, oppressively busy industrial future, Hawaii was the place where all worldly cares evaporated.

Consequently, when the government eased foreign exchange restrictions and started allowing overseas travel on April 1, 1964, the first place people of means wanted to visit was Hawaii, and not just because it was relatively close. Years of long-distance acculturation had rendered the 50th state a familiar paradise.

In a way, it was even more familiar than their own tropical islands. The southern Ryukyu archipelago, which includes Okinawa, was controlled by the U.S. military until 1972, which meant Japanese people needed passports to go there as well. Besides, Okinawa carried with it tragic associations since it was the only part of Japan that suffered a land invasion.

For decades, the vast majority of Japanese workers couldn’t afford to go to Hawaii, unless they were lucky enough to get on the popular game show “Up Down Quiz,” whose grand prize was an all-expenses-paid trip to Hawaii. In the ’60s, a 7-day package tour cost 360,000 yen while the average starting monthly salary for a college graduate was only 20,000 yen. It wasn’t until the mid-’70s, when starting salaries rose and tour prices fell with the introduction of Boeing’s jumbo 747, that middle class Japanese began traveling to Hawaii in respectable numbers. Still, a five-night trip to Hawaii was, for most Japanese, something they would have to save years for. And it wasn’t until 1994 that the average monthly salary outstripped the average cost of a package tour: 192,000 yen and 186,000 yen, respectively.

Two things kept the romance alive over the years: the Japanese-related resident community of Hawaii and the Japanese media. Outside of aboriginal Hawaiians and Americans from the mainland, Japanese and Japanese-Americans made up the largest ethnic population on the islands, and they catered to Japanese tourists with an acute understanding of what made them different from other visitors. Tourists from Japan could spend a long period of time on the islands without ever having to use English or, for that matter, emerging from their comfort zone of Japanese food and activities. Well-to-do Japanese bought condominiums there as vacation homes.

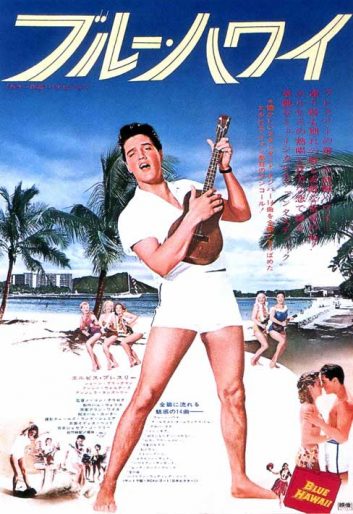

Movie poster for the Japanese version of the film Blue Hawaii.

Hawaii became the preferred destination for celebrities who needed time away from the usual sort of attention fame brings in Japan, but, inevitably, the Japanese media followed them. By the late ’80s, the “Hawaiian Travel Special” was a fixture on every TV station during the long New Year’s holiday break, with features showing famous Japanese actors and pop stars relaxing on the beach, fishing, and eating exotic food. In recent years, major music acts have put on large stadium concerts in Hawaii and set up package tours, complete with local transportation and accommodations, for their fans from Japan. Local Hawaiians rarely attend.

Since 1988, when Japanese citizens no longer required visas to visit the U.S., Hawaii has increasingly been an easy, affordable destination, especially now with the dollar lingering around the 100 yen line. However, the number of Japanese visitors has decreased over the past two decades. It peaked in 1997 at 2.2 million and was down to 1.5 million in 2015. This drop has been of great concern to the Hawaiian tourist industry, but it isn’t as bad as it may seem.

Young Japanese are not traveling abroad as much as their parents did at their age due to financial limitations and a more insular temperament. While all outbound travel has decreased steadily over the last ten years, only travel to Hawaii has seen a slight increase. The main reason for the upturn is repeaters, whose numbers are climbing as the huge baby boom generation reaches retirement age. Members of this cohort have disposable income and grew up during the most intense period of Hawaiian-longing. That’s why, despite the overall travel decline, every Japanese airline is boosting flights to Hawaii and they’re all operating at 80-90 percent capacity.

It is often said among Japanese themselves that Japan is not a place to relax; it is a place for work, for fulfilling the obligations that come with living. This mindset is a legacy of the postwar “industrial miracle” that changed Japan from a destroyed country into one of the world’s most powerful economies. The long hours and selfless devotion to company and family paid off, but at a huge price to Japan’s collective peace of mind. In many ways, “longing for Hawaii” is still the highest representation of freedom from worry and stress.

This mindset was revealed on a recent TV program, which profiled a matchmaking service that brings together single Japanese women and unattached men of all ethnic backgrounds who reside in Hawaii. One young Tokyo woman who enrolled in the service said her hometown is “too frantic to live in.” Though Tokyo is one of the safest, most orderly capitals in the world, any Japanese person watching the show will understand exactly what she means. As the center of Japanese business and government, Tokyo is inescapably crowded and hectic.

When asked if her parents objected to her looking for a foreign mate, she answered, “Not at all. They like Hawaii, too.” Obviously, whatever cross-cultural difficulties her parents might have with regard to their daughter’s non-Japanese spouse would be balanced out by her living situation. They could visit her any time, and everybody wants an excuse to go to Hawaii.

Philip Brasor and Masako Tsubuku are freelance writer-translators who live just outside of Tokyo. They write regular columns on media, money, and housing for The Japan Times.

This essay is part of a Zócalo Inquiry, Is Hawaii Guiding America into the Pacific Century?

*Lead photo by LUCY PEMONI/AP Images. First interior image in the public domain. Second interior image courtesy of Hal Wallis Productions/Paramount Pictures.