An illustration depicts Bald Knobbers riding in black horned masks. Courtesy of the Route 66 Museum and Research Center, Lebanon, Missouri.

When I was seven years old, in 1983, my family took a road trip from Stillwater, Oklahoma, to Branson, Missouri, a family-oriented resort town deep in the Ozark Mountains. Our destination was Silver Dollar City, a Christian-owned theme park that is like Disneyland reimagined as a 19th century mining village, all built around a cave that was a bat guano mine in the 1880s. There, I went on a frightening dark ride called Fire in the Hole.

In the waiting area, the walls were covered with paintings of men in creepy hoods, twisted devil’s horns protruding from the sides. Once we got in, my fear only heightened. It was a roller coaster—in the dark. At first, we rode past a town on fire as villagers cried for help. Then it looked as though we were going to run off a broken track on a cliff’s edge. A steam engine’s horn blared, the train’s headlight appeared close enough to run us down, and finally we hurtled toward a wall of fire before plunging down to splash in a pool of water. I was sobbing as we walked out.

Six years later, when I was 13, I came back to Silver Dollar City with my best friend’s church group. We rode Fire in the Hole six times in a row. We thought it was awesome. There was something primal about its frights—runaway trains, walls of fire, and the strange shadowy men with the bizarre devil horns—especially for kids brought up Christian.

All these years, the images at the Fire in the Hole entrance have stuck with me. Who were those hooded men in devil horns supposed to be? Recently, I did some research and learned that the villains in the ride, which is still operating, are based on a real 19th-century Ozark vigilante group called the Bald Knobbers. Though they never lit a town on fire—that part of the ride is completely invented—the real story of their rise is a terrifying parable about what happens when government fails and violence reigns.

Inside the Silver Dollar City dark ride Fire in the Hole, a “Bald Knobber” blasts riders with his cannon while a coyote eerily howls close by. Courtesy of Creative Commons.

When I called Dr. Matthew J. Hernando, a professor at Ozark Technical College and author of Faces Like Devils: The Bald Knobber Vigilantes in the Ozarks, he told me that “Fire in the Hole” –which he has ridden many times—“is basically a bunch of nonsense.” For the real story of the Bald Knobbers, Hernando explained, you have to look at southwest Missouri’s peculiar history. In a region where the Civil War had laid waste to the rule of law, ne’er do wells like the notorious James-Younger gang and vigilante groups like the Bald Knobbers emerged to fill the void of authority. Admirers saw them as righteous folk heroes; adversaries regarded them as murderous thugs.

Under the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Missouri was admitted to the United States as a slave state at the same time Maine was admitted as a free one. But Missouri never voted to secede from the Union. While few official battles between the Union and Confederate armies occurred in the Ozarks, the region was rife with Confederate guerrillas, Union militias and “irregular” troops of mixed, sometimes shifting loyalties. In his book, Hernando describes how the local people were beset by these groups, suffering rapes, beatings, pillaging of their farms, and even gruesome murders with heads displayed on sticks. By the end of the war, violence became accepted as a way to solve problems, or at least extract revenge, in the Ozarks.

The only known Bald Knobber mask in existence, belonging to William James of St. Louis, who’s a descendant of a Bald Knobber. Masks like these were particular to the Christian County Bald Knobbers. Courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri.

In the Taney County section of the Ozarks, early white settlers wanted to maintain their pre-war way of life, based on subsistence agriculture, hunting, and fishing. They were mostly Democrats who had sided with the Confederates. New homesteaders, largely Republicans who had sided with the Union and were drawn by the Homestead Act of 1862, had ambitious plans to develop the region so that it would thrive in the rising American industrial economy.

Outlaws tormented homesteaders, but the Democrats in charge of local government let them off the hook. Period newspapers claimed that 30 to 40 murders were committed in Taney County between 1865 and 1882, but none resulted in a conviction.

One gang, led by brothers Frank and Tubal Taylor, ran rampant in Taney County, flaunting the cash they’d stolen. After a local businessman criticized the brothers, he found three of his prized cattle starved to death because miscreants had cut out their tongues.

In response to this and two murders that went unpunished by judges who were related to the Taylors, 13 upstanding citizens including merchants, wealthy business owners, and lawmen met to form the Committee for Law and Order. They signed pledges to “respond to the call of the officers to enforce obedience to the law.”

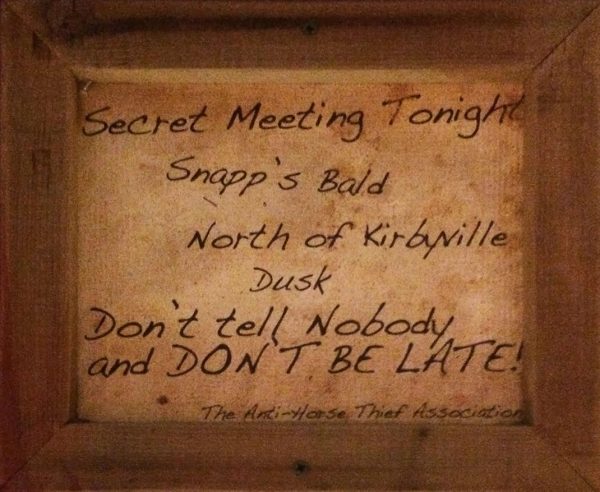

On April 5, 1885, the Committee called an organizational meeting on a treeless ridge (a “bald knob”) known as Snapp’s Bald near Kirbyville, just north of the Arkansas border. Roughly a hundred men listened as Nathaniel “Nat” A. Kinney, a Union Army veteran, delivered a moving speech over the bloody shirt of one of the murdered men. A charismatic jack-of-all-trades, Kinney had settled on a livestock ranch with his family in 1883, started his own Sunday School, and joined fraternal orders. After his rousing oration on Snapp’s Bald, the group voted to elect him “chieftain” of the Committee, which became known as the Bald Knobbers.

Shortly thereafter, one of the Bald Knobbers, a storekeeper whose shop was frequented by Frank Taylor, refused to advance him any more credit. According to Faces Like Devils, Frank smashed up the store. The next day, the storekeeper filed an indictment against Frank, who quickly posted bond before returning to the store with Tubal and a friend, shooting and wounding the storekeeper and his wife.

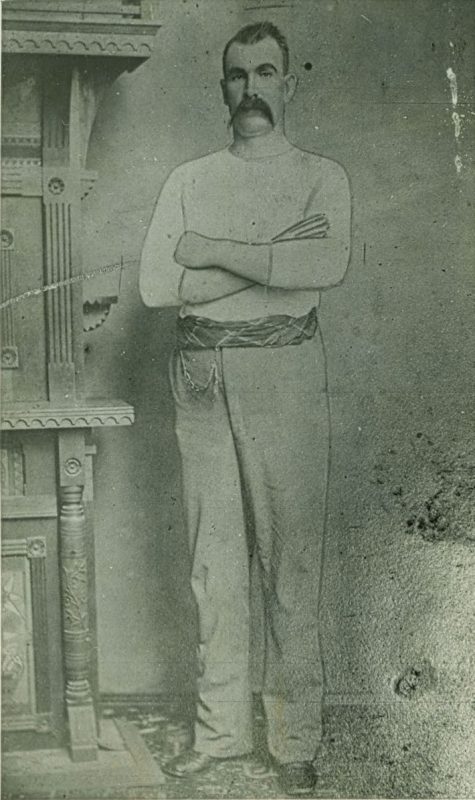

Nathaniel “Nat” N. Kinney, the towering chieftain of the Taney County Bald Knobbers, pictured in 1883, the year he moved to Forsyth, Missouri. Courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri.

The Taylor brothers surrendered to the local sheriff, confident they would be released after a brief jail stay. But that night, a Bald Knobber posse rode their horses into Forsyth, broke into the jail, and took the Taylors. The next day, the brothers were found dead, hanged from an oak tree outside of town, with a sign affixed to Tubal’s shirt that said, “Beware! These are the first victims of the wrath of outraged citizens. More will follow. The Bald Knobbers.”

After the hanging of the Taylors, the Bald Knobbers didn’t have to kill anyone else; they could rely on their reputation to intimidate whomever they considered undesirable. At first, they targeted criminals for intimidation. Once they drove the outlaws away, they zeroed in on anyone who might obstruct an economic boom. Some locals, usually Democrats who had supported the Confederacy, were outraged, asserting that the Bald Knobbers were biased, oppressive bullies.

In the summer of 1885, citizens in nearby Christian and Douglas Counties invited Nat Kinney to help them establish their own Bald Knobber chapters. He assisted. But these new branches of the Bald Knobbers ultimately developed goals completely opposite to those of their Taney County counterparts.

Unlike the merchants and politicians going on “night rides” in Forsyth, Hernando explains, the newer Bald Knobbers in the northern counties were mostly poor and politically powerless subsistence farmers, often Democrats and strict Baptists. The northern Bald Knobbers resented incoming homesteaders and the railroad tie company shipping from Chadwick, particularly because it attracted “blind tigers”—saloons where men would waste their wages on high-proof liquor, gambling, and prostitutes. In Christian and Douglas counties, Bald Knobbers enforced religious morals, not just laws, wrecking the bars and whipping men believed to have neglected their families, kept “lewd women,” or lived as polygamists.

The cave outside Chadwick, Missouri, where the Christian County Bald Knobbers would hold their meetings. Courtesy of the Route 66 Museum and Research Center, Lebanon, Missouri.

These vigilantes met in caves, and Faces Like Devils details how they distinguished themselves by wearing elaborate, nightmarish masks of black fabric with cut out eye and mouth holes sewn buttonhole-style with red thread. The eyes and mouth might be circled with white. Then two horns made of the black fabric and stuffed with cork would be attached to the masks, and sometimes red tassels would be added to the tips of the horns. Even though these Bald Knobbers saw themselves as righteous men of God, they wanted to startle their enemies by appearing like devilish “horrid, hideous creatures,” according to Robert Harper’s 1888 New York Sun exposé on the group.

Meanwhile, back in Taney County, the original Bald Knobbers disbanded in 1886; with surprising swiftness, their vigilantism had transmuted into the leadership of the Republican-run local government, enabling them to punish their enemies the “lawful” way, by jailing them for tax evasion, embezzlement, and minor hunting and fishing violations. In less than a year they had become the crony government they originally fought: When Nat Kinney shot and killed a 19-year-old antagonist, he was cleared of all charges by the Bald Knobber sheriff for reasons of self-defense. But then Kinney and the sheriff were killed by Anti-Bald Knobbers, a group of the vigilantes’ enemies who had unsuccessfully petitioned the state government to let them form a militia and retaliate.

Back in the northern counties, the Bald Knobbers were disbanding too; but as a last act, in 1887, they sought revenge on a young Christian County man who said the Bald Knobbers were “no better than a sheep-killing dog.” A mob of about 25 men found him sleeping at his father’s house, along with eight other members of his family, including women and children. The Bald Knobbers broke into the home and started shooting, killing two and wounding two. One Bald Knobber also died.

Sensational news articles about the atrocity spread across the United States, and public opinion of the Bald Knobbers went sour. To an extent, neighbors had tolerated the group’s lashing of wayward fathers and sexual deviants. But the ambush of the family was too much—four Bald Knobbers were charged with first-degree murder, and more than a dozen others faced second-degree murder charges. Eventually three men were hanged while a fourth escaped from jail.

A sign in the exitway of the Fire in the Hole ride references the first large-scale meeting of the Taney County Bald Knobbers, which took place on a treeless ridge called Snapp’s Bald. “The Anti-Horse Thief Association” was a common name among 19th century vigilante groups, but it was never the Bald Knobbers’ name. By Lisa Hix.

Although from our perspective the Bald Knobbers may seem like renegade outliers, in Faces Like Devils Hernando asserts that vigilantism has been a part of America’s culture since its rebellious founding, and our country’s obsession with conquering lawless frontiers has only fed that impulse. It’s a legacy of violent uprising we may not be entirely free from today.

“All U.S. vigilante groups are in some way a representation of the American value of self-government,” Hernando said. “We are a society that is founded, at least in part, on the firm belief that the people have the right to create their own institutions of government, what is referred to as the ‘right of revolution,’ expressed right there in the Declaration of Independence. If the government is not doing what it’s supposed to, if it’s not protecting the people’s liberties, if it’s not serving the people’s interest, they have the right to rise up and replace that government. The problem is, you cannot do that on a continuous basis and have a stable society.”

Today, the Bald Knobber name lives on in Branson—in distorted depictions that cast them as an outlaw gang, like in the outdoor drama, “The Shepherd of the Hills,” or as goofy hillbillies, like in the Baldknobber Jamboree variety show. Then of course, there’s the entirely fictional ride about pyromaniac Bald Knobbers in Silver Dollar City. Last November, I returned to Fire in the Hole for the first time in nearly 30 years, with my 12-year-old niece. This time I could see the premise was ridiculous. A wall mural I hadn’t noticed before read: “In the year ‘1873’ this Entire Village and Countryside was Destroyed by the Great Fire which was set by Baldknobbers after a Saturday Night Fight at the Tavern … 58 Citizens served as Firemen.”

The ride, though, had changed and become more tame. My niece, who had heard the story of my 7-year-old crying jag multiple times, looked at me like I was crazy at the end of the ride. “That wasn’t scary at all.”

Lisa Hix, an associate editor at CollectorsWeekly.com, has written for Yahoo, Jezebel, KQED, and the San Francisco Chronicle.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.