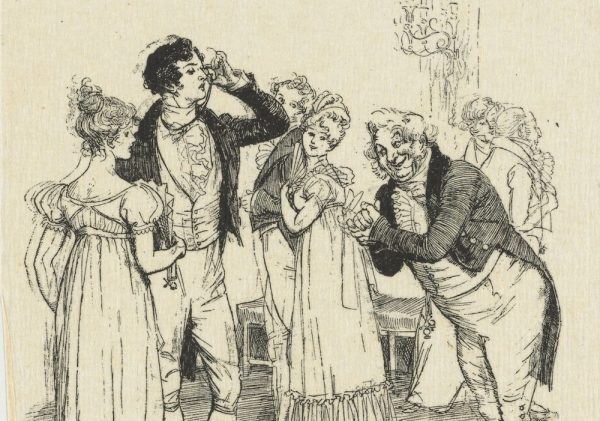

Was the socially maladroit Mr. Darcy in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice autistic? A wave of new novels, including The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time and Tilt: Every Family Spins On Its Own Axis, are re-examining the mental condition, focusing on autistic characters’ inner lives rather than their disabilities. Revisionists also are re-assessing classic novel characters like Mr. Darcy and Boo Radley of To Kill a Mockingbird. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Is autism cool?

It is in literature, as novels featuring characters on the autism spectrum have become so frequent that they’ve spawned a new genre: “autism lit,” or “aut lit.”

Many of the works put a positive spin on autism. These autistic characters have abilities as well as disabilities; they exist not only as mirrors or catalysts to help others solve their problems, but as active agents with inner lives.

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, first published in 2003, did more than any other book to give life to this genre. Christopher Boone, the narrator, is a 15-year-old autistic savant; that is, he can perform computer-like math in his head. He also has trouble with language and social interactions, the two primary symptoms of autism. Still, he’s shown to have an inner life that includes many opinions, as well as hopes for the future. Perhaps of greatest importance is that he has the ability to pursue his goal of solving the mystery of who killed his neighbor’s dog.

A successful book that breaks new ground will breed many imitations. Back in the late 1970s, Robin Cook’s Coma introduced the medical thriller to the world. And so Curious Incident has been followed by a wide range of novels, including the pseudo-science fiction novel, The Speed of Dark (2005); fiction-that-reads-as-memoir, such as Daniel Isn’t Talking (2006) and Tilt: Every Family Spins On Its Own Axis (2003); young adult novels such as Mindblind (2010); and the light-hearted The Rosie Project (2013) and its sequel, The Rosie Effect (2014).

Of particular interest is M is for Autism (2015), the moving result of a collaboration of young students at Limpsfield Grange, a school for autistic girls. Boys are diagnosed with autism four times more often than girls, and the face of autism is almost always that of a young boy. This novella looks at some of the special issues that young women face, and by doing so it’s an exception in the genre.

Back to our young men, though: Somewhere on the journey from Curious to Rosie a transformation occurred. The smart but anti-social and clueless Christopher Boone morphed into the smart and somewhat clueless but also charming husband and father Don Tillman. Don is a professor of genetics in The Rosie Project and an equally successful professor in New York in the sequel.

On this same literary journey, the perceived limitations of these autistic characters have been turned either into strengths, or into obstacles that, once overcome, become strengths. For example, many of these fictional beings “miss social cues” (a stereotype, but like many stereotypes based in some reality), and therefore don’t dissemble or manipulate the way that neurotypical people do.

Lou Arrendale, the hero of The Speed of Dark, is a thoughtful young man with a superior moral sense. He lives in a not-too-distant future when autism can be cured in infancy. Lou was born just a little too late for that, but now science has invented a way to “fix” autism in adulthood, and Lou has to decide whether he wants to give up the advantages of his condition for the sake of fitting into society’s mold. It’s difficult to imagine a character debating this question 20 years ago, let alone 50.

Mindblind is a contemporary young adult novel; no scientific advances here. But Nathaniel Clark, the hero and narrator, not only drives the action, he ends up being a rock star, at least in his own social circle.

Perhaps the most powerful statement, though, is uttered by the heroine’s therapist in M is for Autism: “You are a wonderful teenage girl. And you have autism. The truth is, you will need some support and guidance with life’s inevitable ups and downs but you can have a glorious, fulfilled life, M, and this is the truth, too.” In other words, even without medical intervention or a touch of wishful thinking, there’s no reason for people on the spectrum to give up on their future.

This positive prediction wouldn’t be made about to Boo Radley, the recluse from To Kill a Mockingbird. Rumors surround Boo: he eats raw squirrels; he drools most of the time. Though these are indeed rumors, from what we do learn about Boo, he may well be autistic. Regarded as a shadowy, sinister figure, Boo ends up saving Scout’s and Jem’s lives, but his “reward” is to have his brave act go unrecognized. We last see him as Scout leads him by the hand back to his lonely existence.

Autism lit is not without controversy: Many readers object to the prevalence of the autistic savant. And in fact, most of these protagonists are gifted: Christopher Boone, for example, is about to sit for his A levels in math, a heady accomplishment in England, where the book takes place. Nathaniel Clark is graduating college (with a double major, he reminds us more than once) at the age of 14.

In reality, savant skills are as rare in the autism spectrum community as they are in the neurotypical one. Those who dislike the novels for this reason cite the 1988 film Rain Man in which Dustin Hoffman plays Raymond Babbit, who can memorize a thick phone book in one night. As novelist and cultural observer Greg Olear wrote, “Thirty years later, the belief persists that autistics can reliably count a pile of toothpicks at a glance. This is a powerful negative stereotype that autistic children (and their parents) must overcome.”

But there doesn’t seem to be any stopping “autism lit,” exploitative or not. In fact, the fascination with the autism spectrum and fiction has launched yet another literary trend: the “retroactive diagnosis.” Some readers now believe that Mr. Darcy of Pride and Prejudice is on the spectrum; that’s the explanation for his reserve. Some readers suspect that the narrator of Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf falls into this category as well. The word “autism” didn’t exist, the theory goes, before World War II, and that’s the explanation for why Austen and Hesse didn’t label their characters themselves.

I’m not ready to jump onto this bandwagon. Calling Mr. Darcy autistic is a way of granting stature to people truly on the spectrum who don’t need your literary charity, thank you very much. But there are worse alternatives. (The retroactive diagnoses might apply to Boo Radley.)

In the world outside victimhood, we remain in the midst of an unexplained epidemic of autism spectrum disorders; some sources say that as many as 1 in 68 children are being diagnosed with the condition. And even with the onslaught of fictional characters on the spectrum, much of the story of autism remains untold.

There’s a saying that has been variously attributed to Temple Grandin, the autistic professor of animal science and advocate for the humane treatment of livestock, as well as to the autism advocate and author Stephen Shore, which has become one of those aphorisms that belong to the world: “If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.”

Since each story is different, we can expect the category of autism lit to swell, ideally with more portrayals of people on the spectrum who have jobs, partners, and most of all, purpose.

Donna Levin’s latest novel, There’s More Than One Way Home, was published in May of this year by Chickadee Prince Books. Her papers are part of the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University and her novels are part of the “California novels” collection in the California State Library.