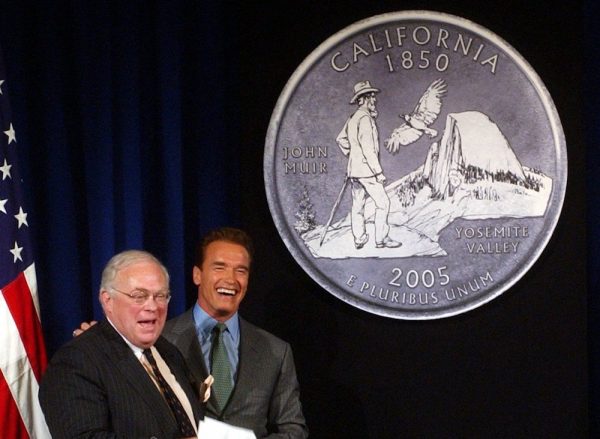

Kevin Starr, the former State Librarian and author of an influential and critically acclaimed multi-volume history of California, with then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, unveiling the design chosen for the California Quarter during ceremonies in Sacramento on March 29, 2004. Photo by Rich Pedroncelli/Associated Press.

California has had many chroniclers — some critics, some boosters, some cheerleaders, some dour polemicists. It’s only natural that a vast state defined by its extremes—political, geological, economic, and otherwise—would rarely be portrayed from the center.

But one of the paradoxes of the Golden State is that the greatest historian of California, someone who absorbed the writing of previous scholars and scribes, found a way to render this state of far left and extreme right, of ocean and desert, of triumphant and shameful, almost right down the middle. One of the many things we might mourn with the passing of historian Kevin Starr, last January, was that the USC professor and longtime state librarian was able to frame this contradictory place in a way that earned respect from almost all corners.

Even the best attempts to document the state—at least since Hubert Howe Bancroft’s work in the 1880s—took a specific point of view or subject within the California experience. Mike Davis wrote powerfully of Los Angeles as a betrayal of democracy and civic life, a harbinger of a dystopian future. Joan Didion captured the despair of the poor, the ennui of the privileged and the soul-death of the counterculture: Much of her best work is about leaving California and looking back in anger, as in her devastating book Where I Was From. Walter Mosley writes novels about the black experience in what was once called South Central. Before all of them, Helen Hunt Jackson conjured the romance of the mission years with her novel, Ramona, a fantasy the state’s boosters would sell to those yearning for a prelapsarian Mediterranean paradise.

Starr, by contrast, did something radical: He let the state’s intense drama and tendency to extremes tell itself. His books—in the series called Americans and the California Dream—documented the triumphs and the betrayals. Through this method, he showed California to be not merely a state but a kind of civilization unto itself, like medieval Venice perhaps, or ancient Babylon.

Rather than writing, as some charged, from a complacent and conservative Chamber of Commerce point of view, Starr wrote from a position that was roughly and intelligently centrist, but indebted to strains of Cold War and Catholic liberalism. His ardor for the Golden State meant he held it to extremely high standards. And his generosity and openness led him to have the unlikely honor of being friends with everyone from left-wing polemicists to the Republican governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. His books even inspired a (very fine) symphonic work by left-of-center California composer John Adams. It’s hard to imagine any other intellectual, before or after, filling all of those roles.

The closest antecedent to Starr is probably Carey McWilliams, the friend of Mencken and John Fante and author of California the Great Exception. But while McWilliams took a broad view of the state, and wrote better than anyone in his time on subjects like Japanese interment and the treatment of migrant workers, his works seems—compared to Starr’s multi-volume, era-by-era California Dream series—like the product of a very gifted and ambitious journalist-author, not a professional historian in the Kevin Starr mode.

“Starr comported himself as if he’d been born in 1920s Oxford rather than 1940s San Francisco. He was a bow-tied, suit-wearing hail-fellow-well-met who mixed heart and angst with an occasionally defensive bluster.” Photo courtesy of Google Images.

Starr himself began his career as an unconventional hybrid: He started reading California as a graduate student in Harvard’s August American Civilization program. But he was also a seventh-generation Californian. Born and raised among poor Irish Catholics in San Francisco, he never lost his love for the Church or the city despite what was clearly a tough upbringing, including a stint in an orphanage, an extended stay in a housing project, living on welfare, and his mother’s nervous breakdown following his folks’ youthful divorce. But after schooling on both coasts and a brief term in the U.S. Army overseas, Starr returned to California in the early ’70s and made his native state his life’s work.

In describing a state known for larger-than-life figures in culture and politics, Starr went right to California’s vast middle. While he wrote eloquently about novelists, architects, and governors, he was often best in chronicling its people—its poor and middle-class—rather than its outliers.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, he recalled scanning the shelves of at Harvard’s Widener Library. “I thought, ‘There’s all kinds of wonderful books on California, but they don’t seem to have the point of view we’re encouraged to look at—the social drama of the imagination.” For all the impersonal forces and outlandish characters Starr describes, his books are largely social histories, though they lack the hard edge or ideological bent of, say, A People’s History of the United States author Howard Zinn, or of Britain’s “history from below” school led by Marxist Eric Hobsbawn.

Starr framed the state as both part of the American West and distinct from it. His extension of Wallace Stegner’s notion that California was like the rest of the United States, only more so, was only one of the motifs that he would borrow from a great novelist.

One irony is that Starr did something that seemed impossible: He wrote about the state out of deep love—his books were, after all, about the California “dream,” a word that appeared in the title of every volume of his monumental history of the state. But Starr also broke through the myths that boosters had used to market the place to the world, with their sales pitches of endless natural bounty, idyllic suburban real estate, and limitless possibilities for self-reinvention.

Starr’s nuanced approach comes across quite clearly in Endangered Dream: The Great Depression in California, which shows the state struggling with economic and social collapse. You can feel Starr’s optimism being challenged too: This was a period in which the Communist left and the fascist-friendly right—both marked by naked racism, especially against the Chinese—burgeoned, and poverty, including child poverty, was breathtaking. Starr describes it all with color and artful detail, but he could also write, in this same volume, insightfully about documentary photographer Dorothea Lange, the stirring sweep of the Golden Gate Bridge and the novels of John Steinbeck.

In other books, Starr used popular culture to illustrate telling aspects of California’s evolution: writing about the importance of outdoor fountains to a water-starved state, or about the dark luminosity of noir fiction, or the tradition of American auto travel and the romance of the road that had its origins in Southern California.

It’s not so much the subject matter that defines Starr’s work—he could write about cuisine, engineering, labor struggles, and everything in between—but what he calls a literary approach in the preface of his first book, Americans and the California Dream, 1850 to 1915: “It seeks to integrate fact and the imagination in the belief that the record of their interchange through a symbolic statement is our most precious legacy from the past. I would like, in short, to suggest the poetry and the moral drama of social experience.”

This method might not work for every country or region, but for California—which would become the world’s leading exporter of imagery, visual and narrative and musical, and which entered the American mind as a kind of fantasy of freedom and wealth—it’s both apt and effective.

Starr the man was marked by contradictions, or at least tensions and ironies. At times, he comported himself as if he’d been born in 1920s Oxford rather than 1940s San Francisco. In his last few decades, especially, he was a bow-tied, suit-wearing hail-fellow-well-met—he mixed heart and angst with an occasionally defensive bluster. But those who knew him as a young man described him as often being courtly and old-school even then.

While Starr wrote memorably about the rough and raw period after the Gold Rush, or the turn-of-the-century Arroyo Culture that incubated the Arts and Crafts movement, or the exiled European artists and intellectuals who migrated to California in the 1930s and ‘40s, he barely touched the era of his own adult life. In the course of eight books, spanning the state’s founding to the early George W. Bush years, there’s an enormous hole, from 1964 to 1989, and he didn’t wrestle with the years after 1950 until he was nearly 70.

It may be that no matter how long we waited, no matter how long he lived, Starr would never have come to terms with the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, which included the emergence of California as the capital of the nation’s counterculture, bohemia’s curdling into Altamont and the Manson murders, several major economic shocks, the development and spread of second-wave feminism, the maturing of Hollywood and the L.A.-based music industry, devastating civic uprisings, the high-tech upheaval of Silicon Valley and the ascent of both Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan as major national figures. These were also the decades when—owing to a major shift in U.S. federal immigration policies in 1965—the Golden State became significantly less Caucasian, and, in part as consequence, began to move from a mostly red to what would become a deep blue state. What would have been in those books, we’ll never know.

This ’64-’89 period may have been too personally close to Starr. And real history is hard to do without serious distance. Coast of Dreams, covering 1990 to 2003, has some great bits, but it’s the one book of his that feels inessential, with brief dispatches on surfers, “Gang Chic,” rich New Agers taking over Big Sur, and Burning Man. (“A liberal application of food coloring,” he writes in a caption, “can bring one to another place.”) Starr was not the only member of the Silent Generation who lost his step trying to interpret the culture of the young or the darker turn that California took: His confession in the preface that “California had gone seriously awry” was shared by others taking stock of gang murders, the Los Angeles riots, and the Northridge earthquake.

It’s likely that Starr’s persistent optimism led him into a dead end. His observation, in the same preface, that, “It would be seductively easy, I realized, to join the naysayers … and I would be considered a deep thinker,” has an almost Nixonian ring. But more broadly, with the rise of the ‘60s counterculture, the hardening of suburban reaction, and the polarization of coastal enclaves to the left and the state’s interior to the political right, Starr simply could not be Starr any more. As the middle class fled because of high prices, a state increasingly defined by rich and poor, and the political center destroyed in battles over immigration and crime and taxes, an ecumenical centrism became as hard a position intellectually as it was politically.

They weren’t the first pitched arguments or flight to extremes that the state had seen: All of them had antecedents that Starr himself had chronicled before. But it may be that in the ‘60s, half a century after Yeats wrote “the center cannot hold,” being California’s man in the middle was no longer possible even for the great chronicler of the continent’s edge.

Scott Timberg is a Los Angeles journalist and the author of Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class. He runs the CultureCrash blog on ArtsJournal.com and tweets at @TheMisreadCity.