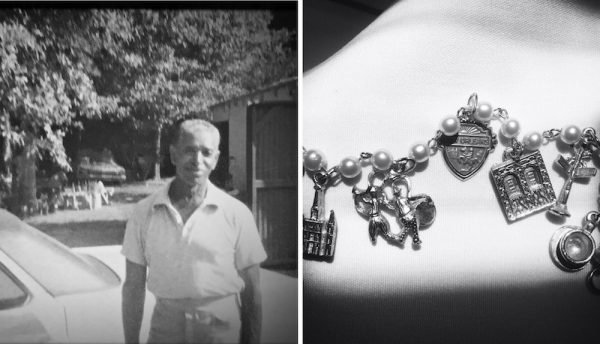

The author’s grandfather, Frank (left); New Orleans charm bracelet, a gift from the author’s grandfather (right). Images courtesy of Lynell George.

Zigzagging through the crush of rush-hour commuters at L.A.’s Union Station, I’m hoping to make up for lost time. Suddenly, out of the edges of my vision, a man crosses in front of me, planting himself directly in my path. In a broad-brimmed Panama hat, cream-colored slacks and shoes to match, he’s a vision of not just another place, but another era.

“Where you from?” he asks.

I hold him in my gaze just long enough to assess the question: Rap? Ploy? Curiosity?

I land on the latter: “Los Angeles,” I say.

Without a beat, he lobs back: “Where’s your mama from?”

I let out an “I give” chuckle. Then: “New Orleans,” I respond. Full stop.

“Okay. Yes, of course.” He says nothing more, moves on so that I may do the same. But as I slide into my seat on the Metro, the exchange cycles through again and again, like always, leaving me wondering how I’m marked and how it shows.

I’m often asked versions of this same question by strangers, always other African Americans of a certain age. Where it might seem a logical inquiry within a train station—a busy hub between here and there, I’ve had it happen in other locales—markets or car washes, the dry cleaners. It’s a way of locating and understanding something essential about who we are, who we’re connected to as Americans—and who we were and what that means in a far-flung place—out of context. It’s a post-Great Migration inquiry. It’s often, in my experience, a “Southern thing”: “Oakland by way of Beaumont”; “San Bernardino by way of Knoxville.” But as time passes, and our favorite uncles and our first cousins become ancestors, I wonder how much longer we’ll be asking, and what it might mean to come from an ancestral elsewhere.

Los Angeles—with its shifting landscape and quick-change acts—is never enough of an answer. It’s seldom the right answer. Even as a native, I understood early, it serves as an incomplete response. That’s why summer still has a tug—why August in particular comes with an emotional pull, a filling up of my senses. Something about the atmosphere shifts, the light, reminds me that it’s right about now that this is when we would start pulling the “other, nicer summer clothes” out of chest-of-drawers; there will be calamine lotion to purchase; a trip to the bootery for sturdy sandals. I can still hear the snapthunk of my mother’s off-white Samsonite train case; I can smell the sharp scent of astringents, of talc, of mosquito repellent. This process was its own season: We are clearing out, getting ready to go “home” for the summer. To the home, I inherited, the one that is marked on me in some both visible and invisible way.

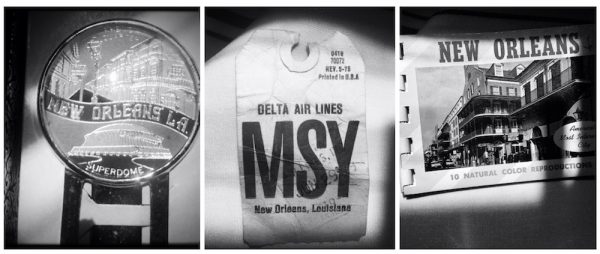

From left to right: Souvenir bookmark; luggage tag from the author’s mother’s train case; memory souvenir book. Images courtesy of Lynell George.

The “George” side of me was more apparent. A good portion of my father’s family had moved to Los Angeles in the 1950s from Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Our reunions were informal but frequent. We spent our big fall and winter holidays together in an expansive dining room on 25th Street, or in early summer gathered around picnic and card tables set out upon sturdy St. Augustine backyard grass. Around these relatives, I saw the connections, it was where I’d inherited my jaw, my browline, my height—I wasn’t stooping down to be heard here. These were clearly my people and they ran as a constant thread through my life here.

My New Orleans family was much smaller and more diffuse and, in certain ways, more abstract—an unexplored idea. That complication, my mother knew, required that we travel there, to sit knee-to-knee with relatives to take part in rituals, both elaborate and quieter ones. New Orleans traveled well enough—its sense-awakening food and spell-casting music—but she knew that there wasn’t anything like witnessing life there first-hand.

If reunion means to reunite with what was left behind—or unfinished—these trips were part of a process of essential bridge-building. They were non-negotiable. Landing in Louisiana in the middle of August was more than a “baptism,” it was a dare—a proving ground. I fought it; didn’t want to be pulled away from my routines, my friends, my familiars. If Los Angeles was a collection of jet-age shaped slick surfaces, Googie diners, starburst decorated dingbats, laid end-to-end, New Orleans, especially in the first few days, felt like something pulled out of the attic: a little rumpled, worn and over-ripe—but a keepsake that I needed to find some place for.

Out of the suitcases came the sleeveless, starched dresses, the flat, thick leather sandals, sunhats and mosquito spray. Each day was a battle with the sticky air—atmosphere that seemed to not just have texture but weight—until we’d settled into it, like the pace, slower, more open-ended, leaving space for come what may.

We’d travel to relatives’ homes and sit in dark rooms, drapes and blinds pulled against the sun. Metal oscillating fans buzzed just below conversations that wandered through all sorts of hard-to-decipher territory. We’d leave that home and my grandfather would slide behind the wheel and drive another few blocks to the next address, another home with a front room adorned with a couple of Queen Anne chairs and a brocade sofa with doilies on the arm rests—again curtains drawn. No matter how hot, however, something sumptuous was always going on in the kitchen, wafting through the prim and orderly rooms. If it was Monday, red beans and rice; if it was the weekend, gumbo. If someone offered you a bowl or plate, you couldn’t say no. Even if you’d just sampled from the kitchen pot before this one.

The sitting, to a pre-teen, seemed interminable; the voices, the thick New Orleans accents—clipped and quick with details that I could barely if at all make out, left me marooned.

Even the souvenirs were odd—embarrassing to my West Coast sensibilities: a baby alligator now stuffed and sewn and dressed up like Batman (with a cape and mask and boots, and felt-cutout bad emblem); salt and pepper shakers with black-face mammies and “uncles” with the words “New Orleans” painstakingly hand painted beneath their aprons. Even my Aunt Elsie’s handmade dolls—peach-faced, wide-eyed debutants dressed for a lavish cotillion—were fabricated out of old, large soda pop bottles, outfitted with a sequined “ball gown” and beneath it a crisp and rustling “crinoline,” the yarn “hair” done up in some sort of antebellum upsweep. (I took that doll back to Los Angeles, where it sat on the highest shelf on my bookcase, untouched for 40 years. She, I imagined—among the Malibu Barbies—probably felt marooned, too.) Who were these people? They were gentle, patient and all heart, but I didn’t understand my place in their story for such a long time.

This wasn’t the New Orleans of French Quarter excesses or fine dining at some swank fine-dining establishments—places my mother couldn’t have visited let alone paused too long in front of—as stipulated by Jim Crow segregation—until she returned with her family in the late ’60s/early ’70s. As I got older, I began to understand that more—and the stories my relatives told. I understood the role of the social aid and pleasure clubs that would help with all manner of contingency plans and safety nets—medical aid, prayer circles, company for shut-ins and most famously, funerals. I understood what the Krewe of Zulu meant—beyond outrageous costumes, throws, doubloons and coconuts. It was insurance when black people couldn’t get any, it was caring for family—blood kin and near or chosen family.

There was magic too: The sudden thunderbursts that unleashed movie-like rain; the steam that rose from the sidewalk right after a deluge. The long, weekend rides out to the “country”—bayous, Spanish moss, June bugs, fireflies. Back in New Orleans proper, my grandfather waking us in the middle of the night to tell ghost stories, or, on the more stifling evenings, putting us all in the car and making a break for the French Quarter to have 2 a.m. hot beignets and cold milk and watch exotic New Orleans nightlife bloom.

My grandfather taught by example: I’d watch him shuck and shoot oysters, salt his beer, demolish crawfish, pace and embellish a story; but more importantly, I saw the way he interacted with the checker behind the counter at the Circle Market, or how he asked after the family of the young man who prepared and packed his po’boys at Eddie’s on Law Street. You looked folks in the eye, you had a kind word or story or a joke to take their mind off their trouble—and when they saw him coming around the corner, he was always greeted with a “Hey there, Dink,” My grandfather moved through his city in a never-met-a-stranger sort of swagger; it was why, I realized so much later, even after my grandmother and my mother traveled to Los Angeles, he could never leave.

One of the first streets in New Orleans that the author’s family lived on. Image courtesy of Lynell George.

I put all of this on a high shelf and shut it away—or so I thought—after my grandfather died in the early 1980s. New Orleans became a place I spoke about in past tense, a site of memory.

Decades later, 10 years into a new century, I closed the door to the gypsy cab I’d hired to carry me to a cafe in the Marigny for work. I was in New Orleans to conduct a series of interviews for a story. I hadn’t been to Louisiana in more than 20 years, and all those rooms, roads and rituals had become ghosts, like my grandfather himself—distant but present. The driver asked as I stepped out, “You sure this place is open? I’ll come back ’round the corner to make sure.”

He was right to worry. The storefront looked as if it wasn’t simply closed for the night, but had been abandoned, like so much of New Orleans had post-Katrina’s flood. It was a foreboding metaphor.

In the early-morning quiet of the street, the buildings—the cottages and shotguns, the curb-to-curb ratios and overall scale much like my grandfather’s old neighborhood near the Treme, memories and voices rushed back, too fast at moments to hold on to the details, like the accents of my relatives—taking some effort to decipher, yet warm.

I heard my name called out. It echoed, bouncing off the hard surfaces—the crumbling concrete of the banquette (sidewalk), the thick-plastered walls. And then again, suspended. The syllables floated in the, humid air, just a shade cooler because it was both early and fall. My interview subject emerged, coffee cup in hand, smiling, open arms: “Welcome to New Orleans.”

He may as well have said, “Welcome home.” I realized in only few minutes, how much was still at the ready: Language. Location. Longing. I was making myself understood as if no time had passed, as if this were my native place, as if there had been no interruption of time or distance or grief.

Sitting in those dark rooms all those years wasn’t for nothing; it was as essential as learning a language, as breathing. The air had weight and so too, history. It was a keepsake from my grandfather, like a charm on a bracelet.

When your birthplace is a brand-new place chosen as your family’s “next chapter” or “new page,” your native roots are still shallow; “home” means something more complex: a mix of the old and trusted with the new and unexpected possibility. It’s extending the line. While we say we’re from a place, from something that you can pin on a map, really, as Americans we’re citizens of ritual and stories. Those summers marking time in a faraway place gave me not just perspective, but a sense of myself in the world—a prism, perspective and inherited past.

As another August approaches, I already feel that pull, a catch in my heart. Though I have now begun to visit annually, mapping my own, very personal version of the city, I haven’t had the courage to return in the high heat of late summer, to see what will spring up in that very particular New Orleans. But I do know this: The next time I’m asked where I’m from, I’ll go straight for the essence, to the very heart of the matter.

Lynell George is a Los Angeles-based journalist and essayist. Currently an arts and culture columnist for KCET | Artbound, she’s a former staff writer for both the Los Angeles Times and LA Weekly, and the author of No Crystal Stair: African Americans in the City of Angels (Verso/Doubleday). She’s currently at work on a new collection of essays and photographs: After/Image: Los Angeles Outside the Frame for Angel City Press.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.