Watching a solar eclipse from a ship in Indonesia in 2016. Photo courtesy of Bill Kramer.

On August 21st this year, I will log my 26th solar eclipse and my 17th total solar eclipse. August 21st is when parts of the contiguous United States will fall in the path of a total eclipse for the first time since 1979. An eclipse happens on those rare occasions when the paths of moon and sun are in alignment, and the new moon covers the view of the sun from certain parts of earth.

I’m what we call an “eclipse chaser.” It’s a self-appointed title. On the website I run, eclipse-chasers.com, I host a log where people from all over the world can record how many they’ve seen. The highest right now is 33 total eclipses. It’s a place online for people like me, people who spend all their vacation time and travel money to observe these indescribable phenomena.

I spend the day before, and then the morning of an eclipse, in nervous anticipation. Every cloud could be an advance scout for an army coming over the horizon. Wind changes are a big deal. Small alterations in humidity are noted. Should we move? Should we set up here? Will it be clear?

In the minute before first contact—that moment when the moon touches the solar disk for the first time—my anticipation grows. Then comes that first little dark edge across the sun. That little bite confirms that the numbers are right. Relief.

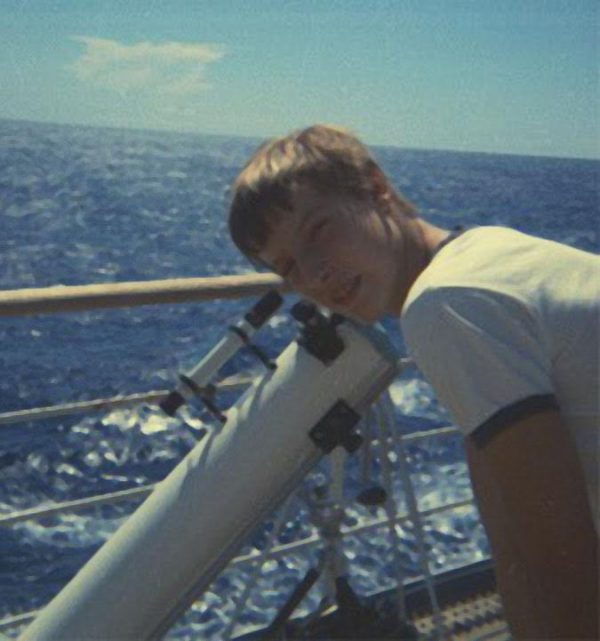

The author on his first eclipse-watching trip in 1972. Photo courtesy of Bill Kramer.

Slowly the moon covers the last of the bright sun and the light falls off quickly. Sunset colors fall across any clouds that may be in the sky. If you are looking in the right direction and have a great view you might even see the moon’s shadow racing across the land towards you. Or you might see shadow bands moving across a flat area like vaporous ghosts making the light shiver around them.

And then the eclipse goes total. It’s dark yet not pitch-black. The horizon glows. Bright stars appear. The sky takes on a deep blue color. And where the sun once shone is a black circle surrounded by a shiny white corona—the circle of solar gases. It’s a magical eye floating in the sky. Streamers of light extend like glowing hairs. Time seems to flip into hyper-drive. Before you know it the eclipse is ending.

The finale is the best part. It only lasts a few seconds. The solar disk peeks out. The light from that one speck of sunlight quickly overwhelms the corona. The effect is called the diamond ring because that is what it looks like.

I don’t have a favorite eclipse among the many I’ve seen. All of them are great. And all of them are different. An eclipse chaser can look at a photograph and say, for example, oh yeah, that’s from the 1983 eclipse in Indonesia. Somebody might ask how I know. Well, because each corona is different. The corona is constantly changing.

Most eclipse chasers will tell you their first eclipse was the best. I was in elementary school when I developed an interest in astronomy and I got involved with the local astronomy club at Youngstown State University. In 1970 some members came back from an eclipse on the eastern coast of the United States, talking about what a great experience they’d had. The director of the planetarium said that he was organizing a cruise to intercept the next total eclipse, in 1972, when I would be 13 years old. I got down on both knees and begged my parents. They agreed and my parents and I were among the first ones to sign up.

We saw that eclipse in middle of the North Atlantic. In 1973 we went to Western Africa to see the next one. Then we didn’t see another one until 1980.

An image of totality from the author’s first eclipse-watching trip in 1972. Photo courtesy of Bill Kramer.

I was lucky in my profession: I majored in computer science, graduated from an engineering school with a computer science and engineering degree, and started my own business in 1985. So I had some flexibility. Whenever it was economically feasible I’d go to see the next eclipse. When my wife and I were first getting serious she found a book at my place—a NASA publication of upcoming eclipses, with a sticker over the front that said “Bill’s travel guide.” She had to know how it was.

So I kept chasing eclipses with my wife, and when we had kids we dragged them along. This summer our grandson, who was just born in November, is going to see the eclipse. So it’s a three-, four-generation tradition.

I particularly remember the eclipse of ’99. When we got back from our trip, we found out my dad had died the day after. I didn’t get a chance to tell him how it had gone and I felt bad about that. It’s one of those things that hits you. So my wife and I decided then, hey, let’s try to see all of the eclipses from now on.

I’ve missed a few, though. Sometimes it’s a question of weather. In 2015 there was an eclipse in March visible from Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago. I skipped that one. Many of those who went saw their cameras malfunction due to the low temperatures.

I’ve never been clouded out and been unable to see an eclipse. Germany in 1999 was the closest I’ve come to that, but it’s never actually happened. Knock wood.

Probably the most difficult eclipse trip I’ve been on was in Zimbabwe. We landed in Harare, missed our connecting flight to Bulawayo, and had to rent a bus for a group of 20—on a Sunday morning—then switch to a caravan of smaller vehicles. My wife and I rode in the luggage car, which broke down a couple of times before we reached the lodge after dark. All this after an overnight flight from London. The next day every vehicle in our caravan broke down. We ended up observing the eclipse at a road rest area—that is, a giant baobab tree. We thoroughly enjoyed the eclipse, under clear sky, and have many memories to share with those 20 eclipse chasers.

Eclipses bring together professional astronomers and amateur chasers like me. There’s a lot of cooperation and citizen science. This summer the Citizen CATE experiment will collect video recordings of the eclipse from citizens across the United States, so scientists can watch about two hours of inner corona dynamics.

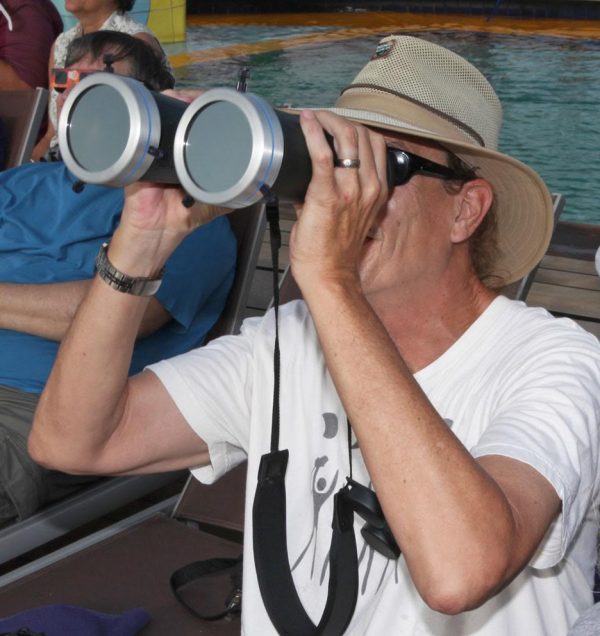

The author watching the partial phase of the 2016 eclipse through binoculars with removable solar filters. Photo courtesy of Bill Kramer.

Sometimes we meet at conferences to discuss logistics and science. A grad student might say, “I’m doing work on the F-Corona, specifically in the transition zone, so if you could take photographs of this exposure I’d really appreciate it.” An amateur can send in pictures and get a mention in some scientific paper. It’s fun. And that’s how science gets done.

Because I love math, one of the things that always enthralled me about eclipses is how they are calculated. How do astronomers confirm the timing so precisely, down to the second? I started reading books on how to do it, and then wrote computer programs on how to do it.

For the August eclipse, we’ll just be with friends and family. We’ve found a location just north of Nashville because two years ago my wife and I drove the eclipse path all the way from Wyoming back through Kentucky to check out different location options. Of course, if the weather doesn’t look very good at that location the night before—I’ll use satellite data to check—we’ll get on the road to a better spot. At least I will! I can’t guarantee that my daughter and grandson are going to want to do that. They may say “Nah, it’s not worth it.” I’ll be saying, “Yeah, it is.”

I’m looking forward to this one because we’re bringing a lot of people who have never seen an eclipse before. It’s always fun to get their reaction immediately after totality. So what did you think? “It’s nothing like you described.” Well, yeah, but how can you describe it? There’s almost a religious epiphany that occurs. It’s the eye of God looking down on you. There’s nothing that really puts words to it. They just say, “I had no idea.” And then “When’s the next one?”

I love that. “When’s the next one? Where is it?”

Bill Kramer is a retired computer engineer who lives in Jamaica most of the year. He enjoys using his telescopes, drawing cartoons, and maintaining the eclipse chasers web site.