A mural commemorating Prince in Minneapolis’ uptown neighborhood. The city’s unique demographics were as important as the pop virtuoso’s genius in shaping his music. Photo by Jim Mone/Associated Press.

The pop music genius Prince Rogers Nelson, better known to most of us as Prince, made his national television debut on American Bandstand in 1980. Performing “I Wanna Be Your Lover,” his first big hit in the United States, he gave the country its first taste of the Minneapolis Sound, an infectious blend of rock, R&B, funk, and New Wave that would become a significant force in American pop music during the 1980s, ’90s, and early 2000s. An astounded Dick Clark, struggling to interview the shy singer and guitarist after the performance, told Prince the music he played was “not the kind of music that comes out of Minneapolis, Minnesota.”

Clark had it all wrong: This was exactly the kind of music people played in Minneapolis. The Minneapolis Sound, which influenced musicians from Janet Jackson to Sheila E., has come to be practically synonymous with Prince, thanks to his classic songs such as “Little Red Corvette,” “Erotic City,” and “Kiss.” But although Prince was its high priest, he was not its author. The Minneapolis Sound was bigger than one diminutive, enigmatic, driven-genius kid from the city’s north side. It was the offspring of ambitious school-based music training put in place by polka-loving European settlers, and the prodigious talents of a small group of black musicians who migrated to the area during the first half of the 20th century. It had been brewing in the small, easily-forgotten black section of a vanilla city for decades. It was the result of a cultural accommodation that was characteristic of the Twin Cities’ unusual ethno-musical heritage, a mix of styles that its vastly outnumbered black musicians—Prince and others—turned to spectacular advantage.

The story began with the region’s first outsiders: Europeans from Norway, Sweden, and Germany, and whites from northeastern U.S. states who poured into St. Paul and Minneapolis in the middle of the 19th century. They were pulled by cheap land and milling jobs on the banks of the Mississippi River, and they displaced the native peoples in the area. By the close of the 19th century, Minneapolis had grown into a sizable city of more than 200,000, one New Deal-era study of the region estimated.

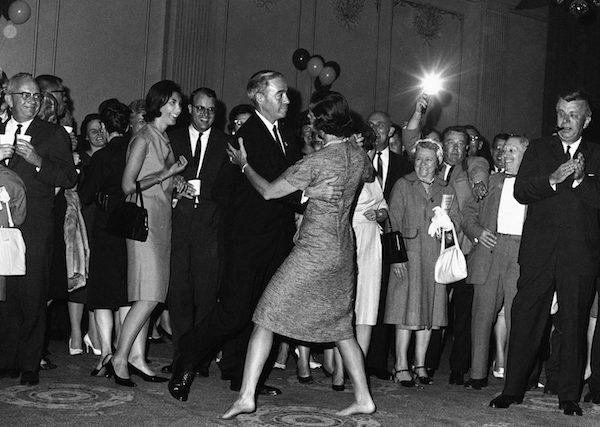

White Minnesotans loved polka music, which borrowed from European folk traditions. Pennsylvania governor and 1964 presidential hopeful William Scranton and his wife courted Republican delegates from the state by dancing the polka. Photo by Paul Vathis/Associated Press.

These Europeans who settled in Minneapolis brought their folk music traditions with them. The musical migration could not have happened at a better time, or in a better place. Early Minnesotans had always placed a high value on music. Ethnic folk music, orchestras, early ragtime, minstrels, brass bands, and vaudeville all were part of Minneapolis’s early music tradition. By the turn of the 20th century, the city had the state’s first symphony orchestra, and boasted numerous music venues that attracted performances by the country’s best musicians.

Polka made its appearance during this time. A combination of different European folk musical traditions, polka or “pulka,” which is Czech for “half-step,” originated in eastern and central Europe in the 1820s, spreading throughout the continent by the 1830s and then, with migration, into the United States. It took hold in northeastern cities and in the upper midwest, as European migrants moved west (the “Polka Belt”), taking up regional variations along the way. Americans loved polka’s energy and vitality, and the ways it connected them to the Old World they missed.

The music thrived in Minneapolis—and inspired a strong commitment to musical education. Around the turn of the 20th century, city leaders institutionalized the town’s love of music through its schools. All public school students in Minneapolis were trained in voice, instrumentation, and music reading. The Minneapolis board of education said the intent was to increase “participation and appreciation of music,” and to provide poor and working class immigrants and their children with the tools to play, read, and write music. This had the effect of keeping alive the folk music traditions that Europeans had brought with them to the state, and would breathe life into the growing polka scene.

The Minneapolis Sound, which Prince and his band The Revolution popularized in the 1980s, was a blend of white and black musical styles. Here, in 1985, the musicians accepted the American Music Award for best single for “When Doves Cry,” in Los Angeles. Photo by Doug Pizac/Associated Press.

But it wasn’t just polka that benefited: Free music education also helped young Prince to lay the groundwork for the Minneapolis Sound. His family, like the European immigrants who invented polka, didn’t have the money to pay for musical instruments or lessons. But with the public schools providing these resources, Prince spent every second he could in his high school’s music room, practicing multiple instruments, honing his sound, and making demos.

Minneapolis’s polka love provided a perfect entry point for wildly creative black musicians like Prince in another way, too: by forcing them to mix with white culture in ways their brethren in other cities never had to. Black people have lived in Minnesota since before the state was founded. Blacks from Canada traded with Native Americans in the 19th century, and slaves (both slaves and escaped former slaves) also were a presence in the state. The first free black settlement in Minnesota was founded along the banks of the Mississippi in 1857, and in the years after abolition, migration increased. Minnesota’s growing liberalism and the state’s willingness to enfranchise black men sent a signal to many that they would be treated fairly in the northern metropolis.

Still, there were never very many black people in the area. Between 1880 and 1930, the black population in Minnesota grew from a negligible 362 to a still tiny 4,276. African Americans made up just 1 percent of the population in 1930; even when Prince was born, in 1958, the percentage of the state’s black population remained in the single digits. (It’s no wonder that the comedian Chris Rock joked in the 1990s that only two black people lived in Minnesota: Prince and Hall of Fame baseball player Kirby Puckett.)

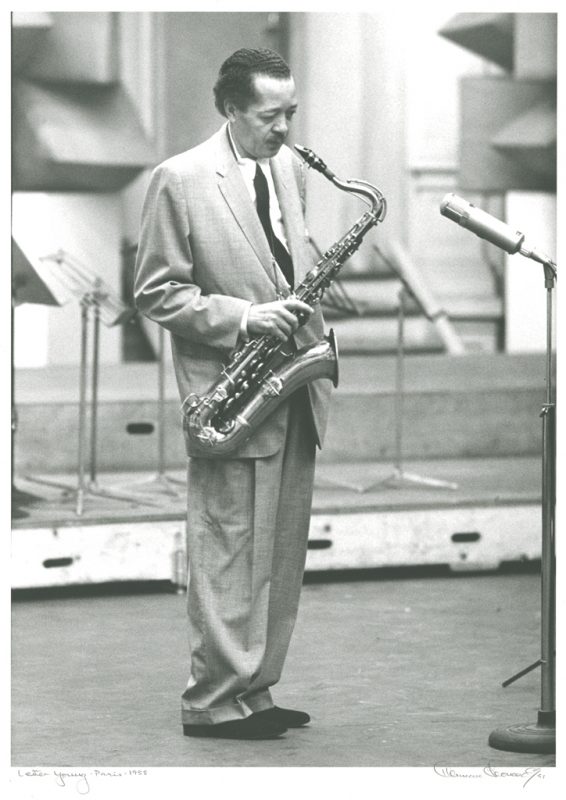

But their small numbers didn’t diminish the impact that blacks had on the music scene—rather, it may have amplified it. While white Minnesotans played their polkas, black music migrated up the Mississippi, with minstrel shows, ragtime, jazz, and the blues all gaining enthusiastic, if small, followings in Minneapolis. Black musicians started thinking of the city as a place where they could live and thrive. Early black musical migrants included Lester “Pres” Young, the talented tenor saxophonist, and the jazz pianist James Samuel “Cornbread” Harris, II (whose son, Jimmy “Jam” Harris, became a well-known R&B songwriter and producer and an important figure in the popularization of the Minneapolis Sound).

Prince’s Yellow Cloud Electric Guitar, 1989. Image courtesy of the Division of Culture and the Arts, National Museum of American History.

Others followed. The parents of producer Terry Lewis (Jimmy “Jam”s’ musical partner), and those of guitarist Dez Dickerson (who played with Prince’s band, the Revolution), migrated to the Twin Cities during this same period. Prince’s parents made the journey too: Mattie Shaw, a singer, and John R. Nelson, a composer and pianist, both moved up from Louisiana in the 1940s. They met through Minneapolis’s small but vibrant black music scene, also known as the “chitterling circuit,” in the 1950s. Like many black migrants, they landed in North Minneapolis, a formerly Jewish area, where Prince was born and raised.

Because the black music scene in Minneapolis was so tiny, black musicians who hoped to make a living by performing played for white audiences whenever possible. Segregation reinforced the musical color line, with most white audiences wanting to hear classical music, jazz standards, polka, or pop music. Black musicians learned to accommodate them, and developed a vast musical range. Cornbread Harris, for example, learned to play “polkas, mambas, salsas, and calypsos,” says Prince biographer Dave Hill. Black musicians’ virtuosity expanded their own community’s musical vocabulary, melding a new family of sounds into the jazz, blues, and R&B they played for black listeners.

Prince’s generation followed the pattern. In the early 1970s, when Prince was a teenager, the numbers of black people in Minneapolis were still “small enough to be ignored,” according to Hill, and white pop music continued to dominate. Prince was schooled in black musical forms like R&B, funk, and soul, but there was still only one small, low-frequency black radio station, so he and his contemporaries also listened to rock and folk artists such as Crosby, Stills & Nash, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, fellow Minnesotan Bob Dylan, and Joni Mitchell.

Lester Young, 1958. Photo by Herman Leonard. Courtesy of Herman Leonard Photographs, Archives Center, National Museum of American History.

Prince’s unique virtuosity made it possible for him to forge a new style from the wide variety of white and black genres that he and his city loved. Even as a high school student, he could hear a song in his head and translate it to sound. He played several instruments by ear, including guitar, piano, drums, and bass guitar. He coolly mimicked masters like Carlos Santana note for note. Folk influences like Dylan and Mitchell course through Prince’s work with his first band, Grand Central, which played rock-tinged funk and soul. By the mid-’70s, punk, indie rock, and New Wave—the music that floated around the “vanilla market” in the city at the time—had filtered into his recordings, too. This musical collage is apparent on Prince’s first album, For You, which was less a commercial release and more a statement of what the young musician could do: Minneapolis Sound lite, with flares of the sexually provocative lyrics for which he would become famous.

By the time Prince recorded his third album, 1980’s Dirty Mind, he had refined the sound. Instead of showcasing his ability to play multiple instruments and diverse musical tastes, as his first release had, Dirty Mind showed Prince’s ability to blend his influences to create an entirely new sound. It was a giant leap creatively. Hailed by critics as a landmark, Dirty Mind put Prince and the Minneapolis Sound on the map. Songs like “when you were mine,” “Partyup,” and “Uptown” (an ode to the bohemian Minneapolis neighborhood that Prince identified with), were punk-funk music, incorporating heavy New Wave and rock overtures smoothed out with R&B. Erotically-charged songs like “Head,” “Dirty Mind,” and “Sister” shocked—and delighted—listeners and critics alike. Rolling Stone said the album was “a pop record of Rabelaisian achievement,” and music critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine called it a “stunning, audacious amalgam of funk, new wave, R&B, and pop, fueled by grinningly salacious sex and the desire to shock” that “set the style for much of the urban soul and funk of the early ’80s.”

The press anointed Prince the next Jimi Hendrix—the new black rock royalty for the ’80s. In fact, he was more than that. Mining the sounds that reverberated in his unique corner of America, from polka to punk, Prince forged a style that was just right—in spite of, or perhaps because of, its oddball roots in black and white culture. Over the next three decades, Prince released dozens of albums and stored away enough recordings to release two or more albums a year for a century. His was a singular talent, of a sort we’re unlikely to see again. But without Minneapolis’s crazy musical mixture in his past, he might have remained only a prince, instead of becoming an emperor.

Rashad Shabazz is an associate professor of Justice and Social Inquiry in the School of Social Transformation at Arizona State University, and researches and writes on race, gender, power, culture, and geography. The author of Spatializing Blackness: Architectures of Confinement and Black Masculinity in Chicago, he’s now at work on a biography of the Minneapolis Sound.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.