Disneyland exported its own Main Street USA to its Hong Kong theme park. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

It is the self-consciousness of the idea of Main Street—from its origins in a Nathaniel Hawthorne sketch of New England, to Walt Disney’s construction of a Main Street USA, to the establishment of ersatz Main Streets in today’s urban malls—that makes it so essentially American. Main Street has been used in myriad ways to describe very many different things—from the crushing power of convention to the thrill of new entertainment, from the small town to new big city neighborhoods.

Main Street’s meaning could change quickly. In the 1920s, to invoke Main Street was to call up an image of the dullness of provincial life. By the 1930s, Main Street represented the bedrock of America’s embattled democracy. For decades, Main Street stood for the local; today it’s an importable model of planning and development that can be set up almost anywhere.

Main Street bears double political meanings that in turn raise complicated questions about whether the United States lives up to its ideals.

As public space, the American Main Street has always represented an ideal of community, where persons from different surrounding neighborhoods and social classes come together as rough equals. But Main Street also has a history of discriminatory practice going back more than a hundred years. Northern “sundown towns” in the late 19th century and first half of the 20th century policed their Main Streets by warning and expelling anyone who didn’t “belong” after the sun went down. And historically Main Street usually has been defined by the ruling class of the area, with outsiders—by class, ethnicity, religion, color—not particularly welcome.

So even as we celebrate the ideal of Main Street as a space of democratic equality, we should remember—and rue—the reality.

Part of the reality is this: America’s small towns and their Main Streets have died a thousand deaths, but Main Streets also live on and multiply now as never before, as we recreate them in wealthy suburbs and big cities. Over the past 20 years, America has seen the growth of ersatz Main Streets, facsimiles of the real thing, in private shopping places everywhere.

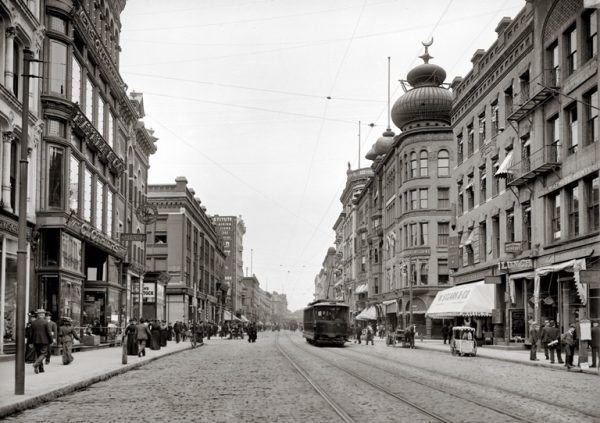

The Main Street of Springfield, Mass. in 1905. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

As the malls of America have become deserted, those shopping centers still clinging to life have strived to emulate the amenities of what they had rendered obsolete: Main Street. They have installed benches, street lamps, grassy areas, and even band stands, providing the feel of public space in the open air, the feel of a community. These facsimiles of Main Street, creations of commercial landscape architects, can be more successful than actual Main Streets, since the national retail brands in ersatz Main Street attract shoppers in the massive numbers needed to make a public space seem genuinely “public.”

If we prefer the authentic to the ersatz, then this new Main Street poses a challenge to the original article. What’s the best response to such a challenge? To do what the ersatz Main Street can’t: provide the individualized shops and restaurants that you won’t find in the ersatz space. The real Main Street also must work harder to draw in people from outside the community, with street fairs and festivals, art galleries, craft shops, and other one-of-a-kind attractions.

Meanwhile, the ersatz Main Street carries its own double meaning: It represents a corporate usurpation of the idea of Main Street—and also an expansion of the idea. Indeed, since the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009, Main Street has taken on a broader meaning and wider constituency than it ever before possessed. It is not just small businesses that Main Street represents. The phrase has become a substitute for what we all share, the American commons. We are either Main Street or its opposite, Wall Street. In this polarized time, we belong to one pole or the other.

One paradox is that the public space of Main Street, regulated spaces that must be open to all, may be harder to police than the ersatz Main Streets, which are private spaces where certain standards of decorum can be swiftly enforced. We don’t usually notice the limitations on our behavior in private spaces, but they exist, often in a sign posted as you enter the space.

Is it possible that the private space of the ersatz Main Street, which welcomes shoppers of all religions and colors, is a more hospitable space than the public space of Main Street? Is the private Main Street more tolerant of difference (as long as you keep your shirt on and wear shoes) than the public space of warring statues and demonstrators armed with torches or guns, where intimidation can be masked as self-defense? If this is the case, it argues for the democracy of the marketplace, which embraces anyone, regardless of creed or color, who has the money to make a purchase.

Today, Main Street faces what some see as an existential threat: e-commerce, which has made any physical shopping space increasingly a luxury. The real Main Street has a future in this digitally dominated marketplace—it is not competing with e-commerce—but the ersatz Main Streets of malls may have more to worry about. Will they evolve as hybrid showrooms where consumers can touch the merchandise before buying it cheaper online? Or as places to pick up merchandise ordered in advance and delivered locally? Or will e-commerce fall victim to its own success and be defeated by Main Street—the infinity of choices and merchandise reviews consuming so much of the shopper’s time that it’s simpler to just go shopping in a store with limited, pre-selected, merchandise?

If Main Street means anything today, it signifies an idealized space where American society can practice its highest values, which include civility, tolerance, and yes, commerce. And Main Street’s endurance, as an idea, demonstrates the authority of myth to nurture a sense of community, even in a society as fragmented as ours.

Miles Orvell is Professor of English & American Studies at Temple University and the author of The Real Thing: Imitation and Authenticity in American Culture, 1880-1940 (John Hope Franklin Prize); The Death and Life of Main Street: Small Towns in American Memory, Space, and Community (Zocalo Public Square Book Prize Finalist); and, as co-editor, Rethinking the American City: An International Dialogue. Orvell is presently working on a book on photography, ruins, and contemporary culture, called The Morality of Ruins.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.