Photo courtesy of Alamy.

Everything, as they say in America, has its price. It has been found that a lack of sleep costs the American economy $411 billion a year and stress another $300 billion. Countless other studies have calculated the annual cost of pain ($560 million), heart disease ($309 billion), cancer ($243 billion), and diabetes ($188 billion). Surf the web at work sometimes? That costs the American people $63 billion a year. Did you show up hungover as well? Tack on another $77 billion.

And while you may not know it, the American government has long put a price tag on Americans themselves. The Obama administration pegged the value of the average American life at $9.1 million. That was up from $6.8 million under the Bush administration.

Americans have developed the penchant for measuring nearly every aspect of their lives in dollars and cents, a process of seeing humans as assets that is so deeply ingrained in American life and decision-making that it constitutes a national philosophy.

Consider the price tags that Americans place on nature. According to “willingness to pay” surveys, dog owners will shell out $7,000 more than cat owners to save their pets, while Americans would pay $257 to save the bald eagle from extinction and $208 to save the humpback whale. (That may sound noble but should be compared to the survey finding that Americans would pay $225 to drop ten pounds.) Think the purple mountain majesties of a Yosemite or a Yellowstone are priceless? Think again. The total economic value of the National Park Service was recently estimated at $92 billion.

Finally, there is the planet itself: Americans are willing to pay $177 a year to avoid climate change and save the world. That’s about 75 percent more than what they pay for cable TV.

What is the impetus behind such calculations? The short answer: cost-benefit analysis. In 1981, President Ronald Reagan passed executive order 12,291, which mandated cost-benefit analysis for all major environmental and health-and-safety regulations. Many of the above examples were the product of such analyses. But if you look back further—before the Reagan era—to the mid-19th century, you ‘ll find that the pricing of everyday life has long been an American pastime. Go back even further, to the 18th century, and you will uncover some of the deep—and disturbing—origins of this American penchant to price everything and everyone.

In 1830, for example, the New York State Temperance Society measured the social damage produced by excessive drinking by pricing the overall cost to the city. “There cannot be a doubt,” the society concluded after a series of in-depth calculations, “that the city suffers a dead yearly loss of three hundred thousand dollars” due to “time spent drinking,” “drunkenness and strength diminished by it,” “expenses of criminal persecutions,” and “loss to the public by carelessness.” An 1856 article titled “The Money or Commercial Value of Man” in Hunt’s Merchants Magazine—the first national business magazine in America—valued the education of New York children at a profit of $500 million to the country.

In 1910, an article in The New York Times headlined “What the Baby is Worth as a National Asset” utilized Yale economist Irving Fisher’s money valuation of human beings to deduce that “an eight pound baby is worth, at birth, $362 a pound.” By 1913, as eugenics became the rage, the National Committee for Mental Hygiene asserted that the insane were “responsible for loss of $135,000,000 a year to the nation.”

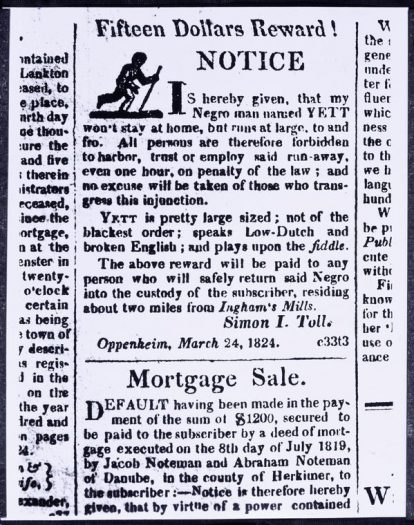

Reward notice for bilingual runaway slave, Oppenheim, New York, 1824. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Such acts of social pricing, while rare in the early 19th century, were ubiquitous by the early 20th. The common thread running through these examples is that the men (and they were nearly all men) who made these calculations were imagining American society as a capitalized investment and its inhabitants as income-generating units of human capital.

Aspects of everyday life such as education, mental health, or alcohol consumption could only be given price tags if one treated American society and its residents as a series of moneymaking assets, thus measuring their value in accordance to their ability (or, in the case of hungover employees surfing the net, their inability) to generate monetary income. This uniquely capitalist way of conceiving of the world, which I have called “investmentality,” was already poignantly on display in that 1856 Hunt’s Merchants Magazine article which priced the value of a child’s education.

“The brain is … an agricultural product of great commercial investment,” noted the author, and the “greatest problem of political economy” was how to “produce the best brain and render it most profitable.”

Today, as the term “human capital” crops up everywhere and countless self-help experts encourage Americans to become more productive by “investing in yourself,” an investmentality has achieved the status of common sense.

The investmentality that sparked the pricing of everyday American life emerged out of the rise of American capitalism. The key element that separates capitalism from previous forms of economic organization is not market exchange or monetary spending (those have been around for thousands of years) but rather widespread capital investment. Such investments are acts through which various aspects of everyday life—be they natural resources, industrial factories, cultural productions, or technological inventions—are reconceived as income-generating assets and valued as such. As capital flowed into various investment channels across the United States in the 19th century, distinctly capitalist quantification techniques escaped the confines of the business world and seeped into every nook and cranny of society.

Like capitalism itself, the pricing of everyday life is not an exclusively American phenomenon. Similar examples of investmentality and social monetization first appeared in 17th-century England and can now be found across the globe. What distinguishes America is the enthusiasm with which our elites embraced money measures. As early as the 1830s, Alexis de Toqueville recognized that “as one digs deeper into the national character of the Americans, one sees that they have sought the value of everything in this world only in the answer to this single question: how much money will it bring in?”

There are various reasons why the United States embraced the pricing of everyday life more than other nations—including the long-standing American tendency to leave much of the responsibility for the allocation of resources, cultural production and economic development in the hands of private capitalists rather than public states.

Yet one reason demands a few final words: American slavery. The “chattel principle” and the rise of an economic institution in which human beings were actually bought and sold helped to jumpstart, legitimize, and normalize the pricing of everyday life. On the rare occasions when early Americans did seek to evaluate social developments in monetary values, slaves served as their main source of both inspiration and data.

The earliest instances of the pricing of everyday American life I discovered in my research were from South Carolina in the 1710s—the colony with the highest proportion of slaves and the most capital invested (especially in large rice plantations). By the 1740s, South Carolina Governor and slaveholding planter James Glen anticipated the invention of Gross Domestic Product two centuries later by calculating the income generating “value” of all inhabitants of the colony at £40,000 a year.

Up north, similar developments were afoot. In 1731, Benjamin Franklin priced the social cost of a smallpox epidemic in Philadelphia by calculating each loss of life at £30 because that was the going price of slaves in the city. He was not alone. “Calculating the value of each person, in a pecuniary view, only at the price of a negro,” the newspaper called the Weekly Magazine estimated the monetized worth of all Americans as “equal to nearly one hundred million sterling” in the 1790s.

It was, in short, often the institution of slavery that set important historical precedents by first enabling early Americans to price the residents of their young nation, be they free or enslaved. By the mid-19th century—following a half-century in which southern investment in human bodies (alongside northern investment in real estate, railroads, and factories) had fanned the flames of American investmentality—slavery finally came to an end. The pricing of everyday life, however, was just taking off.

Eli Cook is an assistant professor of history at the University of Haifa. An historian of American capitalism, he is the author of The Pricing of Progress: Economic Indicators and the Capitalization of American Life.