When a Japanese Akita named Taro bit the lip of a 10-year-old New Jersey girl in 1991, police seized the dog and a judge ordered him destroyed. Taro’s owners appealed to a higher court, while the canine, incarcerated at a county sheriff’s office, awaited execution. Newspapers dubbed him the “death row dog.”

A few years later, a Portsmouth, New Hampshire judge, in a modern version of excommunication, ordered a Labrador mix named Prince to vacate the city after killing a rooster.

And in 2014, a pit bull named Dream that bit a child was executed in Denver while an appeal was pending, apparently due to a courthouse paperwork mix-up.

In a large number of these cases across the United States, it is the canine itself on trial. The dog, not the owner, is charged. The dog, not the owner, is convicted. And the dog, not the owner, is punished for its crimes. When it comes to capital punishment, dogs sometimes attain a human-like standing in our courts. This practice may feel decidedly modern and particularly American, the inexorable dark side of our excessive pampering and “humanization” of our furred friends. At a glance, it isn’t even that different from pet boutiques, gourmet food, luxury lodging, and the like. But scholars trace the roots of humans putting animals on trial back millennia, long before we began showering creature comforts on our canine companions.

One remarkable case involves crops, disease, and some especially pernicious rats in 16th century France. Rodents descended on Autun, a medieval town near Dijon, destroying the barley crop and multiplying rapidly. In 1522, after numerous extermination attempts had failed and Autun was on the verge of a famine, residents turned to the only option they had left: They put the rats on trial. They took their case to the town magistrate, who relayed it to the bishop’s vicar, who ordered the animals to appear in court. The vicar also appointed one of France’s rising legal stars to defend them, a Burgundy-born jurist named Bartholomew Chassenée.

Chassenée was no fool. He knew he was fighting an uphill battle. The power of the Church was supreme, and the voracious rodents didn’t exactly make sympathetic defendants. (This was two centuries after their ancestors had brought the Black Death to Europe.) So Chassenée did his best to delay and derail the trial. He argued, for example, that the rats were too spread out to have heard the summons. In response, the vicar asked every church in every parish harboring the animals to publicize the trial.

When the rodents still didn’t show, Chassenée claimed that the journey to into town was too dangerous. Not only would the rats have to travel vast distances to reach Autun, they’d need to avoid the watchful eyes and sharp claws of their mortal enemy, the cat. Surely the vicar was aware, he said, that defendants could refuse to appear at trial if they feared for their own safety.

When that didn’t work, Chassenée appealed to the court’s sense of humanity: It wasn’t fair to punish all rats for the crimes of a few. “What can be more unjust than these general proscriptions,” he asked, “which destroy indiscriminately those whom tender years or infirmity render equally incapable of offending?” The vicar, whether moved by Chassenée’s words or simply exhausted by his objections, adjourned the proceedings indefinitely.

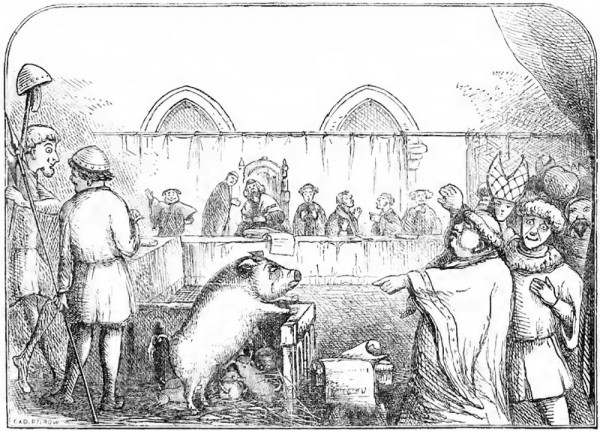

This was just one in a long line of cases of Europeans taking animals to court. The earliest incident dates back to 824, when an ecclesiastical judge excommunicated a group of moles in Italy’s Aosta Valley. In 1314, a French court sentenced a bull to hang for goring a man with his horn. In 1575, the Parisian parliament sent a donkey to the stake for having sexual relations with a man. And in 1864, a Slovenian pig was tried and executed for biting the ears off an infant.

In hundreds, perhaps thousands, of proceedings throughout the continent, animals were treated just like human defendants. The courts appointed them lawyers, heard testimony from witnesses, and considered the possibility of pardon or parole. Even the punishments were surprisingly human—though not particularly humane.

Some creatures were drawn and quartered. Others were stoned to death. And still others were tied to the rack, their cries a form of confession. Due process for animals was so highly valued that when a hangman in Germany took matters into his own hands before the trial of a sow had commenced, he was permanently banished from his village.

What was the point of these trials?

Scholars disagree. Some say they were merely a way to dispatch troublesome animals. But why all the pomp and circumstance? Why not just run a sword through them (or sic a cat on them) and be done with it? Others say the proceedings were an attempt to impose order on an increasingly chaotic world—a means to assert man’s god-given dominion over often unpredictable creatures during a time when we were living in closer quarters with them than at any point in our history. By putting animals on trial, we ascribed them rational thought, and thus we were able to make better sense of their actions. And still other scholars claim that our forbearers simply made less of a distinction between man and beast than we do today, at least for legal purposes. Animals were given human trials because they had human standing in a court of law.

Today, we put a different animal on trial, but the reasons appear remarkably similar. We dragged rats and pigs before judges in medieval Europe because they had violated the cosmic order. Today, we have a new cosmic order: a world where pets are family. When dogs treat us as enemies instead of as friends, they violate this order. And we punish them in kind. We put them on trial in an attempt to restore the world as it should be—or at least, as we would like it to be.

The way we punish these dogs also shares similarities to the penalties of the past. Today’s sentences may be carried out with a lethal injection behind the closed doors of a city shelter, but are they so different from the hanging of bulls in the town square? In the case of Taro the Akita, justice took a more favorable turn: In 1994, after three years and more than $100,000 had been spent on the case, the state’s new governor—acting on a campaign promise—pardoned the pooch.

David Grimm is the online news editor of Science and the author of Citizen Canine: Our Evolving Relationship with Cats and Dogs.

He wrote this for What It Means To Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian and Zócalo Public Square.

Buy the Book: Skylight Books, Powell’s Books, Amazon.

*Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.