Anna Karen Ramirez, 19, poses with her passport at her home in Alamo, Texas in 2009. Photo by Eric Gay/Associated Press.

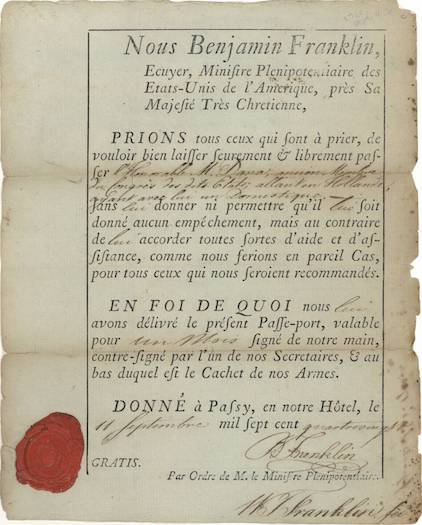

It was originally a European tradition, not ours. But in 1780, needing a more formal way to send former Continental Congressman Francis Dana from France to Holland, Benjamin Franklin used his own printing press to create a new document. The single-sheet letter, written entirely in French, politely requested that Dana and his servant be allowed to pass freely as they traveled for the next month. Franklin signed and sealed the page himself and handed it off to Dana, creating one of the first known U.S. “passe-ports.”

Today, the nation’s passports still display vestiges of their diplomatic origins with a written entreaty to let “the citizen national named herein to pass without delay or hindrance.” But in almost every other aspect, the modern 32-page, eagle-emblazoned booklets bear little resemblance to Franklin’s makeshift bit of ambassadorial decorum. The differences hint at the profound shifts—in appearance, in use, in meaning, in trust, in who got to carry them—that produced a document that came to play a much larger role in American life than originally intended. It’s the story of how a few pieces of paper came to produce new answers to the question, “Who are you?”

“Passe-port” issued to Francis Dana by Benjamin Franklin, 1780. Courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society.

The idea of the passport pre-dates the founding of the republic—one can find early mention of “safe conducts” in the biblical passages of the Book of Nehemiah and in histories of Medieval Europe. Like the Franklin-issued passe-port, these early documents evolved from deals that granted negotiators safe passage through foreign territory. They relied largely on an assumption that the person presenting the papers was the person or group named in them (if any was named at all). But mostly, they were a formality. The privilege and reputation of the limited number of people who frequently traveled usually trumped the need for any formal letter of introduction.

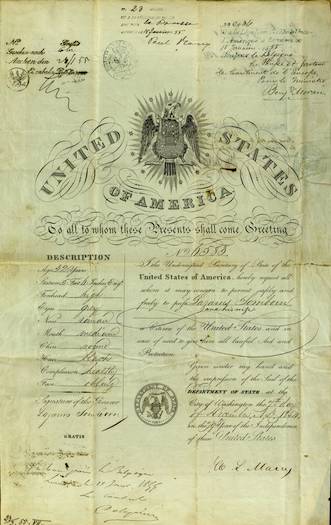

For the hundred years following the American Revolution, the U.S. passport largely followed this historic form too. In the first half of the 19th century, the State Department only issued a few hundred passports per year. Governors and mayors did too, absent any law prohibiting it. The letter-like documents usually only identified the bearer’s name, and could be drawn up to cover a diplomat, a private citizen, a non-citizen, a man’s entire family, or even an entire ship. Passports then were rarely required for cross-border travel. Instead, they were more often used to gain access to private museums, collect mail from a post office, get invitations to social events, or to serve as a souvenir worth framing.

In these early years, the U.S. lacked compelling reasons to identify each person coming in and out of its borders. Immigration levels had been low, and the newcomers who arrived helped fill labor shortages and sparsely populated frontiers. And, unlike citizens of most other countries, Americans had long been skittish about any sort of national identification system. By the latter half of the 1800s, however, demographic and political winds began to shift. First came the laws prohibiting entry of prostitutes and convicts in 1875. Then came the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. During World War I, the U.S. government began scanning for spies, radicals, and communists; and soon after, the Immigration Acts of the 1920s established hard nationality-based quotas. The more xenophobic the U.S. became, the more interest it had in separating traveling citizens from unwanted aliens at its ports.

Passport issued to bearer “and his wife.” Note physical descriptions like “roman” nose and “healthy” complexion. 1854. Courtesy of National Archives.

In response to these new screening demands, the federal government turned to the passport. Through a series of ad hoc laws and policies over the course of a few decades, policymakers radically transformed the passport from a diplomatic introduction for traveling elites into the highly-controlled identification for citizens we’d recognize today. In 1856, Congress granted the State Department sole issuing power over the papers, and limited their use to U.S. citizens. The agency also slowly standardized the passport’s appearance. Engraving plates, signatures, and seals all lent the document a look of authority—giving it a form more like a certificate than a letter (the booklet form came later, in 1926).

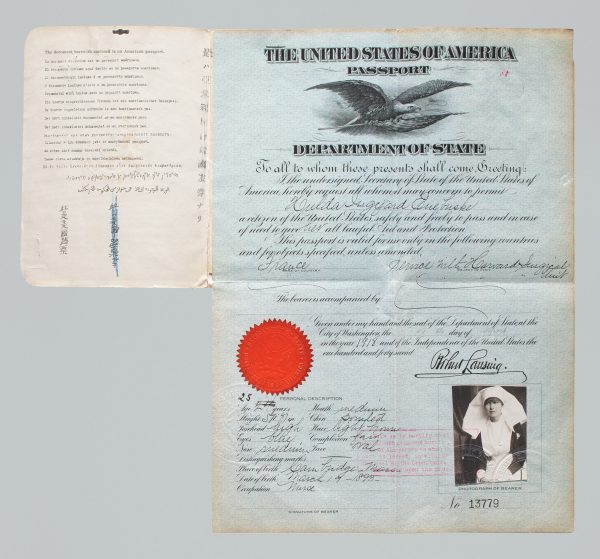

Officials also added markedly modern requirements. Applicants had to produce supporting documents to prove their identity. Forms demanded consistently spelled full names and dates of birth. The passports themselves began consistently listing objective physical features of the bearer, such as height and eye color—shortly replaced by a stark, square headshot photo. Designated government clerks now checked all of the information, all with the idea of creating a verifiable identity that couldn’t be easily assumed or forged. Congress made yet another big change: During World War I, legislators (alongside European nations) passed emergency measures that demanded passports from everyone entering the country. And after the war ended, the requirements never went away.

Between the 1850s and 1930s, these transformations did not go unnoticed. Newspapers filled pages with stories on the “passport nuisance”—the term used to cover the perceived absurdity that the government would force people of the “better” class to be documented like common criminals. Ladies blushed at having to tell their age to a clerk. Gentlemen objected to having their romantic notions of individual character reduced to a generic list of physical traits. Headlines like “W.K. Vanderbilt Tries to Identify Himself” detailed bureaucratic bothers, and the fact that President Woodrow Wilson needed a passport made front-page news. Stories chronicled tales like that of a Danish man who allegedly waited weeks at the border to regrow the moustache in his ID photo. A 1920s advice columnist even recommended a young woman show a fiancé her passport picture as a test to see if he loved her. If he survived the shock of seeing the mugshot-like image, she could safely assume that he truly adored her.

Passport issued to WWI nurse Hulda Euebuske, who appears in her uniform for her passport photo. 1918. Courtesy of State Department, U.S. Diplomacy Center.

In a society that previously relied on local reputation, the idea that the government could replace respectability with an impersonal bureaucratic document seemed, to many, preposterous. Rather than a privilege, some saw the passport as a symbol of eroding trust between citizens and their government.

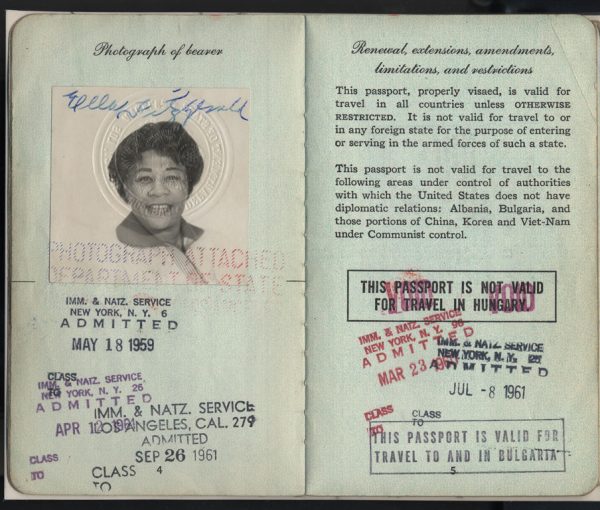

But the government’s new demands for proof of identity hit on another major shift going on in the United States at the time: It was becoming more difficult to immediately recognize who should be considered an American. Citizenship was extended to free slaves. The previous generation’s surge in immigrant labor made it difficult to distinguish old faces from new. Women were beginning to demand recognition independent of a husband. A rising industrial middle class blurred old markers of status. At the same time, prosperity and easier modes of transportation were giving people more reason and means to move around. Travelers of all races and social status now mattered. Having a passport that said you were American took on new meaning for those who had to, and were allowed to, carry one.

The passport had become an instrument of control to help further xenophobic exclusion, but to many of its holders, the document could feel empowering, proof of their belonging. Because the U.S. doesn’t issue any other form of national identification card (state driver’s licenses and Social Security numbers fill the gaps, and can be obtained by foreign residents), carrying a passport became a way for citizens in the wide-reaching federation to assume a national identity. Though few possessed one—less than a tenth of the population for most of the 20th century—the passport, with its elaborate seals and ornamentations, became the supreme authenticator of national identity.

Passport issued to Ella Fitzgerald, 1959.

Courtesy of National Museum of American History.

The passport, more or less, settled into its current form by the late 1930s. Small adaptations in decades since generally followed larger historical trends. Authorities used them in reaction to the country’s fears, attempting to impede communists, terrorists, and scares in between. Tweaks were made in response to new technologies (the new 2017 passports will feature a stiff polycarbonate ID page containing an RFID chip), and to the expanding politics of inclusion (applications now accommodate gender changes and same-sex parents).

Perhaps the biggest change to the passport is that it’s no longer novel. More Americans than ever have one—132 million, nearly quadruple the number 20 years ago. The “nuisance” of producing our small certificates of citizenship at the border has largely faded into thoughtless routine. Identities are blurring as more and more people move around. And, as they do, the little blue pocketbook with its lithographed scenes of Americana, awaiting all those coming-and-going stamps, has become one of the more improbable symbols of American identity.

Craig Robertson is a professor of media studies at Northeastern University and author of The Passport in America: The History of a Document.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.