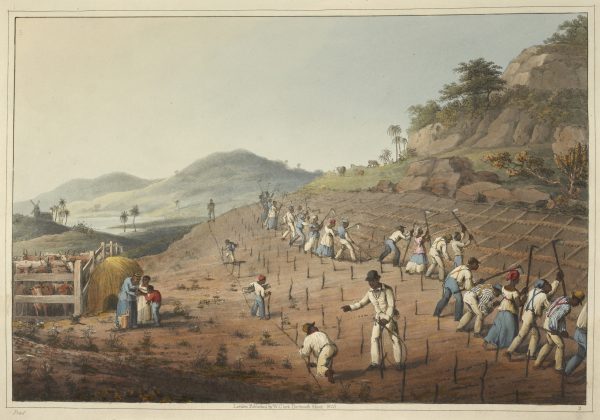

Digging the Cane-holes—Ten Views in the Island of Antigua (1823), plate II. Image by William Clark. Courtesy of the British Library/Flickr.

Today, land developer and businessman William Cooper is best known for founding Cooperstown, New York, home of the Baseball Hall of Fame. But back in the 1790s, Cooper was a judge and a congressman who used his power to market a different sort of pleasure—American-made maple syrup—as an ethical homegrown alternative to molasses made from cane sugar, which was at that time farmed by slaves. He took tours of the Eastern Seaboard, extolling the virtues of “free sugar,” as he called it. Maple sugar never really took off as a sugar substitute, but Cooper’s advocacy made it a favorite of abolitionists, eager to improve society through virtuous goods.

It sounds distinctively modern—fair trade, sustainably sourced, slave free—all familiar touchstones of ethical capitalism in America today. To many of us, morning coffee just seems more enjoyable when the worker picking the beans earns a living wage; a shrimp cocktail, more palatable when it is not processed by children forced to toil in peeling sheds. When trendy apparel is impossibly cheap, and likely the handiwork of exploited laborers, the conscientious consumer seeks an alternative.

Many Americans assume we’re living in a unique moment for ethical commerce, and witnessing the dawn of moral capitalism. But what seems new is actually a 250-year-old tradition, launched by a small cadre of 18th century religious reformers: Quakers and other evangelical Protestants. For activists in both the United States and Britain, sugar was the conspicuous commodity that crystalized the evils of the age because of its role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. It was a product, they argued, that ethical consumers should avoid.

Sugar cane, which is native to Asia, had been rare in Europe until the 15th century, when Spanish and Portuguese merchants discovered that it grew well on the Canary Islands and Madeira. Columbus carried cane cuttings to the Caribbean in 1493, and Santo Domingo became the site of the region’s first sugar mill in 1516. But it was Portuguese slave traders who figured out how to really profit from sugar, forcing captive Africans to work on the equatorial islands of São Tomé and Príncipe. The traders reinvested their profits to buy more slaves to grow sugar in Brazil. In the 17th century, the Dutch took over the slavery-fueled Brazilian and Caribbean sugar operations, followed by the British and French a hundred years later.

The sugar trade was lucrative and competitive because Europeans and Americans had gone sweets-mad. British sugar consumption quadrupled during the 18th century. Production in Haiti, a French colony, increased 40 percent from 1760 to 1791. By the last decade of the 1700s, Britain and France each claimed close to 40 percent of the still-growing commercial sugar market. Enabled by slavery by the mid-19th century, 12 million Africans had been forced into the holds of slave ships, about two million dying en route.

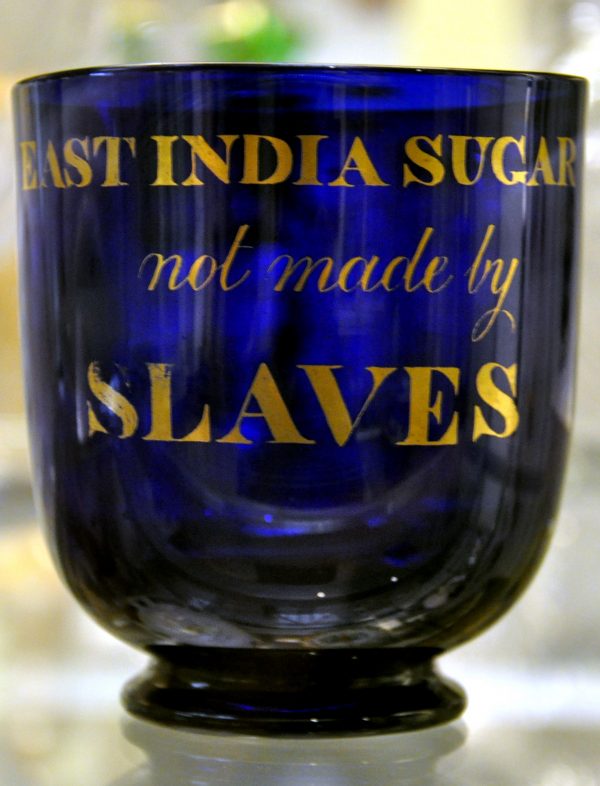

Blue glass sugar bowl inscribed in gilt, “East India Sugar Not Made By Slaves,” c. 1820-1830. Image courtesy of The British Museum.

Abolitionists in Britain organized, petitioning Parliament to end the slave trade. Vested interests, however, fought back, marshalling an array of excuses: Slavery was salutary to British wealth and success, slavery was civilizing to lazy Africans, and if Britain didn’t claim slavery’s wealth, a competitor would.

So the Quakers and their allies looked for another strategy—and found it in 1791. The year had been a propitious one for abolition, with a slave revolt breaking out in Haiti and an unsuccessful but attention-grabbing attempt to abolish slavery pushed in Parliament. Against this backdrop, Baptist printer William Fox published An Address to the People of Great Britain on the Utility of Refraining from the Use of West India Sugar and Rum, urging Englishmen to stop buying sugar on moral grounds. Admired and promoted by Thomas Clarkson, the leading abolitionist in England, Fox’s Address was published in several editions, with a quarter-million copies in print by 1792. Historian Timothy Whelan contends that it was “the most widely distributed pamphlet of the eighteenth century,” exceeding the reach even of Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man.

In response to Fox’s treatise, some 300,000 consumers, mostly women purchasing household goods, boycotted West Indian sugar—and created the first free produce movement in history. The effort was huge by modern standards, involving 2.8 percent of the British population—and helped turn public opinion against slavery. The abolitionist British poet Robert Southey even penned an anthem for the popular cause, writing in a sonnet: “O ye who at your ease/ Sip the blood-sweeten’d beverage,” not caring whether “beneath the rod/ A sable brother writhes in silent woe.”

Britain banned the trans-Atlantic slave trade in 1807, but not because of the protests: Passing a ban gave Britain, which was at war with Napoleonic France, a pretext to attack French shipping. After the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, British consumers again mobilized. The boycotts of the 1820s were bigger than those of a generation earlier, with perhaps more than half a million consumers—mainly female—participating. Leaders formed a Free Labour Company to source sugars in India, and again the protest was felt in Parliament, which abolished slavery in the British West Indies in 1833.

The idea that ethical demand drives supply soon crossed the Atlantic, but isolated American activists like Cooper struggled to be heard. Quaker Benjamin Lundy opened a “free produce store” in 1820s Baltimore. But as an abolitionist editor who set up a printing press in a slave port, he was deeply unpopular. The shop was burgled and, after discovering that enemies paid a black man to commit the crime, Lundy refused to prosecute.

Leadership of American consumer protests fell to African Americans like New York shopkeeper David Ruggles, who advertised in 1828 that his sugars were “manufactured by free people, not by slaves.” The Colored Free Produce Society of Pennsylvania (CFPS) organized in 1830. It was an African American antislavery organization dedicated to educating consumers about who grew and processed their cotton, sugar, and tobacco. The CFPS was a success, quickly boasting 500 charter members who were able to buy 50-pound bags of free sugar.

African American women became the movement’s leaders. Judith James and Laetitia Rowley led the Colored Female Free Produce Society in 1831, composed of members of Philadelphia’s Bethel Church. They drew on women’s purchasing power to force change. At each of the first five Colored Conventions delegates urged black consumers to buy free. One resolution called on “colored capitalists” to invest in free labor stores, and in 1834 African American businessman William Whipper opened one next to Bethel Church. Lundy, the Baltimore Quaker, praised black women’s efforts and said they should be a model for white female activism.

These consumer movements against slave-grown sugar were swimming against a tide. The federal government propped up U.S. domestic sugar interests with protective tariffs, and Americans’ sweet tooth was even sharper than Britons’. On average, each American ate 12 pounds of the stuff each year in 1830, increasing to 30 pounds by 1860. (Per capita, we consume several times that quantity today.) In a world of cheap sweets, Americans cared less about the provenance of their pies and cookies. Abolitionists shifted their strategy to opposing cotton, the great symbol of American slavery, with retailers pledging to work with slave-free suppliers and abolitionists, once again, promoting free produce as a means to fight slavery.

For all the organizing, the crescendo of the free produce movement in America was scarcely audible. Some five to six thousand people abstained from slave-produced products. As many as fifteen hundred joined free produce societies. One source claims 10 percent of Quakers—10,000 in all—were active abstainers.

Today’s activists carry this older movement’s torch. NGOs like Amnesty International decry the use of forced labor in the consumer electronics business, and scholar-activists like Kevin Bales point out the connections between slavery and environmental degradation. Even U.S. states now facilitate ethical shopping. In 2010, California, the world’s sixth-largest economy, passed the Transparency in Supply Chains Act, which requires large firms to disclose efforts to eradicate slavery and human trafficking among their suppliers. The push led some companies to seek out new sources for slave-free cottons and ethically-farmed food.

But sugar is, to some extent, still bloodstained. It’s been 500 years since the first sugar mill was built in the Dominican Republic, but hundreds of thousands of debt-bound Haitians continue to toil in squalor and poverty in the cane fields earning below-subsistence wages. That certainly looks like modern-day slavery. While the Quaker-inspired fight for “ethical capitalism” continues—both as a goal and as an ideal—crusaders have never fully reformed that sweet symbol.

Calvin Schermerhorn is an associate professor and faculty head of history in Arizona State University’s School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies. His most recent book is The Business of Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism, 1815-1860 (Yale, 2015).

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.