All in the family: The Treuer clan, boiling maple syrup. From left: Anton Treuer, Margaret Treuer, Robert Treuer, Caleb Treuer, Evan Treuer, Blair Treuer, Elias Treuer, Luella Treuer, Margret Krueger. Photo courtesy of Anton Treuer.

In my professional life, as a professor of the Ojibwe language and culture, I work to teach and revitalize the Ojibwe language, one of more than 500 tribal languages spoken here before Europeans arrived. I also travel frequently to run racial equity and cultural competency trainings.

In my professional life, as a professor of the Ojibwe language and culture, I work to teach and revitalize the Ojibwe language, one of more than 500 tribal languages spoken here before Europeans arrived. I also travel frequently to run racial equity and cultural competency trainings.

My work is a passion and a calling. Sometimes it surprises people to hear that it grows out of an inheritance I received from both of my parents: my Native American mother, to be sure, but also my Austrian-Jewish father, who fled the Nazis in 1938.

My mother’s Native American roots dominate my looks. I have brown skin and even as a kid often had long hair. At home I was just an Indian. But when I went to school, I was THE Indian. I always caught a lot of looks and comments. My first grade teacher, in Washington, D.C., decided that long hair on a boy was too much of a novelty. She dressed me up like a girl in front of the class. That was the first time I noticed America’s racial fault lines—its limits on opportunity and fair treatment.

The story we all hear of the American dream—work hard, have good morals, and you get sweet American apple pie—I feel like it’s half true. Obstacles persist for people of color and women. We can make it here, but it’s in spite of these barriers, not because there’s a level playing field.

My mother, Margaret Seelye, was born in Cass Lake, Minnesota and raised in the village of Bena, on the Leech Lake Indian Reservation. She is from the Ojibwe tribe, who have inhabited the Great Lakes for millennia. We’re famous for our wild rice and birchbark canoes, but also for our many brilliant activists, warriors, and writers—people like Louise Erdrich, Gerald Vizenor, Clyde Bellecourt, Dennis Banks, and Winona LaDuke.

When my mother was a girl, many of the native families at Leech Lake were reeling from federal policies that took away all but four percent of the land inside the reservation. Her family had buried their dead in the Bena cemetery at Leech Lake longer than America had been a country, but by the 1950s, they had to buy plots from non-native land owners to lay their loved ones to rest next to relatives. They were very, very poor. Harvesting wild rice was less a cool cultural pastime than it was a necessary means of survival. Even as a small child, my mother worked hard—at everything from the Ojibwe seasonal harvest to her school work to her jobs at the local cafe. Eventually she went to nursing school, and was hired to run the new comprehensive health program at Red Lake.

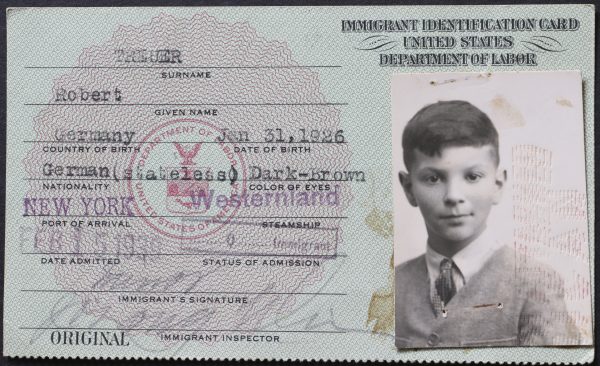

That’s where she met my father, Robert Treuer. He had fled Austria at the height of Nazi power. As a Jewish boy in Vienna, he had to run from armed Hitler Youth. He watched SS officers force his mother to scrub the streets. Many of his family members simply disappeared. My father was 13 years old when my grandparents managed to get him to London. He stayed for a while in a camp for child survivors of the Spanish Civil War, and then moved on to a boarding school in Waterford, Ireland. It took a year for my grandmother, working as a domestic servant in England, to earn enough money to bring the family to America. My father, his parents, and two cousins survived the war. Hundreds of other family members took their last gasps of breath in Dachau, Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and Bergen-Belsen.

Immigration papers of the author’s father, Robert Treuer, whose family fled Austria at the height of Nazi power.

My father, too, had an uphill climb to find his place in America. Once here, he sat often by the radio, listening to news broadcasts and repeating every word uttered, until his English was so clean that everyone thought he was American-born. At age 17, he enlisted in the U.S. Army, hoping to kill Nazis. He was shipped to the Pacific Theater and served honorably in the Philippines. After the war, he worked as a labor union organizer. He married young and had three sons. His first wife was from Minnesota, and he fell in love with the place. Money was tight, but he put in a bid on a piece of tax-forfeited property. Soon he was teaching high school English and planting pine trees on the land by his house. Robert’s first marriage failed, but he stayed in Minnesota, taking work in the Bureau of Indian Affairs that would lead him to Margaret, his second wife—my mother.

He was trying to restart his life and she was building a pathway out of poverty when they joined fates. They moved to Washington, D.C., where my mother pursued a law degree and where I was born. But we spent summers on the property in Minnesota. It was a humble beginning. My parents refurbished a small cabin, which had no electricity or running water. We used to pick wild rice, as my mother had as a child, and traded with our neighbors, the Schlueger family, for milk and eggs. We kept the milk in a glass jug and sunk it in the creek to keep it cold in the summer.

Over time my mother graduated from law school and we all moved home so she could take the Minnesota bar, becoming the first female Indian attorney in the state. Our family’s finances improved dramatically. I soon had three younger siblings. My dad called each of us another victory over Hitler. My mother called each of us another victory over Andrew Jackson.

I didn’t tell my parents about the incident in first grade, when my teacher embarrassed me in front of the class, until I was an adult. I was channeling my warrior ancestors—who I imagined would never have cried over something like that—and internalizing my shame, from that and numerous other small injustices and microaggressions. Over time, I began to feel like the things I learned in school had little to do with me, and that I was not important or relevant in America. It’s a feeling that derails a lot of students of color.

But then my father’s gifts to me kicked in. I had watched him advocate for oppressed people, as a union leader and as a writer for the local paper. I had watched him support my mother’s advocacy for tribes and native people as a defense attorney, law professor, U.S. magistrate, and tribal judge. From both of my parents, I came to realize that the world wasn’t fair, but there was something we could do about it.

My parents raised a high bar, and I was determined to jump over it. College, at Princeton University, taught me that America was a diverse place in much more than name. From friends there I learned to interrogate my own beliefs, in the best way possible. I graduated and returned to the north woods to lean into my native roots. My mother had already made sure that I knew how to hunt, snare rabbits, and process maple syrup, but I set out on a quest to learn more about the Ojibwe language and culture. I landed in the living room of Archie Mosay, a renowned spiritual leader from the St. Croix Reservation in Wisconsin. He spoke English, although he was most comfortable in Ojibwe. I did everything I could to learn what he knew. I spent every summer at our tribal religious ceremonies and eventually went to graduate school in history.

Throughout it all, both of my parents, whose experiences gave them firm faith in their own agency, remained my steadfast supporters and inspiration. Today, I still live on the tree farm my dad started decades ago. I’ve written 14 books on Native American history and the Ojibwe language, and I travel often to do racial equity work with K-12 schools, colleges, and businesses. I have nine children, and together we harvest wild rice, process maple syrup, hunt, and fish. My mother lives around the corner from us.

My father passed away about a year ago, but the pine trees he planted when he first bought the farm stand over 70 feet tall. This forest around me keeps my own roots strong—the ones planted here by my father after World War II, and the ones my mother’s family have nurtured here for millennia, before America was a country. This forest is where I do my life’s work. It contains the challenge and the hope of America. We just need to keep planting the seeds.

Anton Treuer is Professor of Ojibwe at Bemidji State University in Minnesota, and author of Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians But Were Afraid to Ask. He travels around the nation and abroad working for equity, education, and cultural preservation.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.