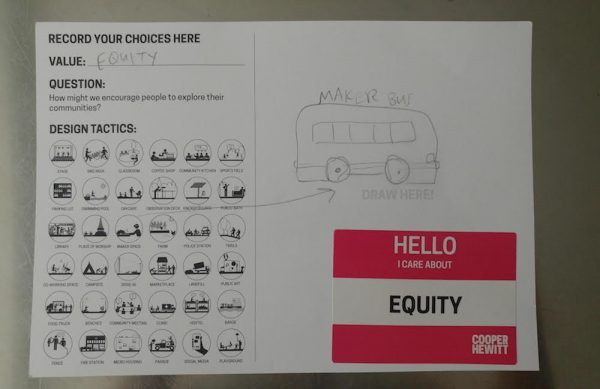

Visitor participation in the Cooper Hewitt Process Lab’s Citizen Design exhibit. Photo by Priya Sircar.

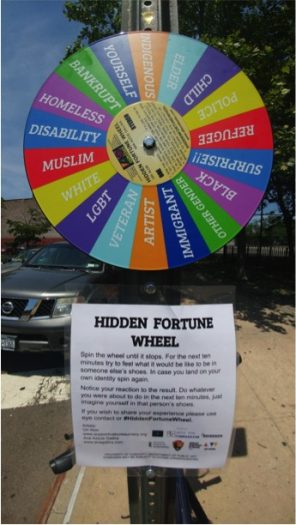

Recently, as I was walking home and mulling over what to write for this essay on arts engagement, I saw a multi-colored pinwheel stuck to a signpost on a street corner, titled “Hidden Fortune Wheel.” Underneath, a sign gave the following instructions:

Spin the wheel until it stops. For the next ten minutes try to feel what it would be like to be in someone else’s shoes. In case you land on your own identity, spin again.

Notice your reaction to the result. Do whatever you were about to do in the next 10 minutes, just imagine yourself in that person’s shoes. If you wish to share your experience please use eye contact or #HiddenFortuneWheel.

I spun the wheel.

For weeks I had been pondering Zócalo Public Square’s invitation to write about arts engagement, specifically about approaches to building arts audiences.

The term “audience” means something very specific to me, as a performer: a person or group of people observing, probably passively, performers who are providing a product like entertainment or experience. The audience may or may not have bought a ticket. Either way, there is a transactional nature to the relationship that—especially if the audience has paid—somehow smacks of the reversal of the balance of power, as if the artists are begging the audience for their attention.

As a dancer, I’m used to this: I often feel in the dance field, we’re begging audiences to sample our wares. And while most performers will tell you that, in return, we get an unparalleled thrill from our audiences through live performance, there is still that element of seeking—whether we seek ticket sales, a full house, applause, or all of the above.

But in my role as a consultant to arts organizations who interface with the public, I generally prefer to use terms that connote service—like “constituents” or “community/-ies”—rather than “audience.” Arts and cultural organizations exist to serve their community or constituency in whatever ways those are defined by the organization. Service implies that the service provider offers something that the consumer actually wants or needs. In other words, we provide something of value rather than something frivolous or extraneous. (Boosting the value Americans place on arts and culture is an ongoing challenge as any arts practitioner knows. While that should not be the goal of arts engagement, it could be a byproduct.)

“Hidden Fortune Wheel” by Ori Alon and Ana Azzue Gallira. Photo by Priya Sircar.

Communities may be defined by external factors, like geographic boundaries, or internal ones, like shared identities or goals. In my consulting work, I often encounter divides within communities. It’s crucial to listen to how communities define themselves and discover which communities exist within others.

If “community” is a more suitable word than “audience” to describe the people served by arts organizations, then is “community engagement” a synonym for “building arts audiences”? Not exactly.

Doug Borwick, of ArtsEngaged, describes activities undertaken by arts organizations: audience development, audience engagement, and community engagement. To summarize, audience development comprises activities “undertaken … as part of a marketing strategy to produce immediate results,” such as sales and donations, in which the principal beneficiary is the arts organization. Audience engagement comprises activities “as part of a marketing strategy designed to deepen relationships with current stakeholders … to improve retention, increase frequency and expand reach,” where the principal beneficiary is the arts organization. Meanwhile, community engagement comprises mission-driven activities “to build deep relationships between the organization and the communities in which it operates” to achieve mutual benefit, based on developing trust and understanding.

I would take it one step further: All arts engagement should be community engagement, because arts organizations should exist to benefit—or serve—their communities, however those communities are defined and whatever form that service takes. The benefit to the arts organization is a moot point, since any benefit to an arts organization is in support of continuing to serve its community or communities.

So, what does service through community engagement look like?

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, takes an interesting approach through its Process Lab, which currently invites visitors to participate in their Citizen Design exhibit. Individually and collectively, participants in Citizen Design take part in an exercise that illuminates design processes while generating ideas for addressing social issues identified by the participants themselves. An example might be addressing accessibility through alternative transportation options. The exhibit gives visitors the opportunity to play with the processes that designers use to solve problems while “envisioning a better America.” Whether or not the resulting ideas are acted upon following the exhibit’s closing in September 2017, the experience of participatory design has the potential to help visitors see and think differently about how to solve community problems in a semi-collective way and, perhaps, to help them feel empowered to do so.

Last November, I was fortunate to organize and moderate a panel that included Chanon Judson of Urban Bush Women and Ebony Noelle Golden of Betty’s Daughter Arts Collaborative. In a powerful performance of Urban Bush Women’s origin story, Judson described UBW’s practice of engaging communities reciprocally, which begins with listening first and then involving communities in co-creation with the artists of UBW. Golden, a frequent collaborator of UBW, shared the notion of community as family, “a team that can get something done.”

Golden also stressed that, in her work as a cultural strategist, she applies the notion of “radical imagination”—not just how we see the world but how we see the opportunity to change the world. We explored the difference, if any, between “change” and “transformation.” Semantics aside, Golden offered a working distinction: Change occurs on an individual level whereas transformation occurs systemically as a result of individual changes.

Whether the goal of an artist or an arts organization is change or transformation, whether it is to make an impact on the individual or systemic level, the process starts with seeing—seeing things differently, or seeing something at all.

Thoughtful engagement done in service to the community, and often with the community, has the power to make us see things—and each other—differently. So, while “community engagement” isn’t a synonym for “building arts audiences,” it should replace the latter as our goal.

Of course not all art has to be community-based or community development, but arts organizations, which act as conduits between art and the public, need to look at all of their activities through a community engagement lens to ensure they continue to have a reason for being.

The pinwheel landed on Indigenous. Hmm, I thought. Okay. And then, in my excitement at finding this example of arts engagement in the wild, I immediately forgot the instructions and instead examined the pinwheel and the rest of the sign, then fairly skipped home as I reflected on what it all meant. I wondered how many people who saw the pinwheel actually spun it, and how many put themselves in the other person’s shoes for ten minutes (or for any minutes). At home, I looked up the artist’s website and the Instagram hashtag.

Was the Hidden Fortune Wheel successful? Did it get me to put myself in an indigenous person’s frame of mind? Not yet. Did it engage me, get me to think critically and to see something in a new way? Absolutely. As James Baldwin said: “The role of the artist is exactly the same as the role of the lover. If I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don’t see.” Lover, artist—I’d add arts organization to that mix. And perhaps to the pinwheel.

Priya Sircar, a dancer-choreographer, actor, and former musician, is a senior arts management consultant with Lord Cultural Resources, an adviser to the Asian American Arts Alliance, and a Cultural Innovators Institute fellow in the EmcArts Arts Leaders program. She hails from Texas and lives in Brooklyn.

This essay is part of a Zócalo Inquiry on arts engagement, produced with support from The James Irvine Foundation.