In classic gay coming-of-age stories, the small-town misfit escapes to the big city—the bigger the better. Robert Mapplethorpe left his home in Floral Park, Queens for art school in Brooklyn and then New York City, where he fell in with a group of artists and eccentrics, most notably Patti Smith, Sam Wagstaff, and George Dureau. “I come from suburban America,” he once remarked. “It was a very safe environment and it was a good place to come from in that it was a good place to leave.”

Mapplethorpe found an artistic oasis in New York. The subversive nature of his photographs—boldly homoerotic and gleefully taboo—stand in stark contrast with the Roman Catholic values of his 1950s childhood. In New York City he was first able to explore his sexual inclinations. In New York City he first picked up a camera. His many self-portraits in those early years—often staring straight at the camera as if looking for his reflection in the lens—point to the fact that there, in that city, he had literally found himself.

I’ve had the luxury of coming of age as a queer person after the violence of Stonewall and Harvey Milk’s assassination, in the era of gay-marriage legislation. And yet I know that our community has paid a price for progress: Queer America is now divided into the “acceptable” and the “perverse.” By acceptable I mean the sexless, “family-friendly” portrayals found on network television and in commercials. Think Modern Family. And by perverse I mean everything else: polygamy, internet chat rooms, the kink community. The old invisibility was dangerous, yes, but a curated semi-visibility is no less harmful. I can be Ellen (funny, devoid of controversy, and successful) or I can be invisible. The game is rigged: Something is always left out of the frame.

Molly Landreth, the Seattle-based photographer known for her revolutionary approach to queer portraiture, grew up in a small agricultural valley in Washington state, an hour’s drive south of the Canadian border.

Landreth left her hometown for Scripps College in Claremont, California. While a freshman, she took her camera on frequent trips to Los Angeles to visit her cousin, spending time with him and his group of queer friends as they got ready for nights out on the town. Too young for LA’s clubs, Landreth was only able to participate by photographing the ritual of primping, accessorizing, and glamorizing. It was her way of reveling in the beauty of sexuality while still piecing together her own, safely out of the frame.

Meg and Renee, 2007, Molly Landreth. Seattle, Washington.

But here the familiar narrative takes a discernible turn. Instead of making Los Angeles her artistic oasis, Landreth went back home. It was there, not the city, where she was able to turn the lens on herself.

Fascinated by the seeming contradictions between her childhood home and the world she had documented in Los Angeles, she began to take “a bazillion self-portraits” with her best friend and fellow photographer Jenny Riffle. They photographed themselves and each other against the landscapes of their hometown, looking for palpable evidence of their shifting identities.

In one photograph taken by Riffle, titled “Wallpaper,” Landreth stands against the swooping bird pattern of her parents’ living room walls, boxed into a small nook created by a Victorian-style chair and a modest side table bearing an oppressively oversized lamp. She looks cramped, out of place, suffocated by the ornate room that can barely contain her. Landreth looks directly at the camera, a practice she would encourage in her later portraits.

Landreth continued to seek out apparent contradictions between subject and environment. From 2004 to 2010, she worked on the Embodiment Project, taking portraits of queer people across the country.

Landreth told me that during this time she often thought of a photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe in which two men pose in a traditional living room, both clad in leather, one standing and holding a chain tied around the seated one’s neck. The picture “queers” an iconic American portrait. Landreth sought to do something similar. Many of her portraits nod to classic images: In one photograph from the Embodiment Project, two women lie together in a parked car at a scenic overlook, the city lights glowing behind them. The scene seems straight out of either a teenage love story or a horror movie, depending on how you look at it.

Clare Mercy, 2007, Molly Landreth. Bellingham, Washington.

When she began the project in the early 2000s, Landreth said, she didn’t see the kinds of queer people she knew in the media—or even in fine arts work from New York City. She didn’t want to keep documenting the curated semi-visible: queers from the upper middle class, or from New York. She turned to the growing world of the internet, entering keywords into MySpace, reaching out to people who seemed to have a complex identity—something unfamiliar. And she wanted them to participate directly in the process, to take back some of the power from the viewer, choosing how they wanted to be represented. She didn’t want her pictures to force anyone into a familiar narrative.

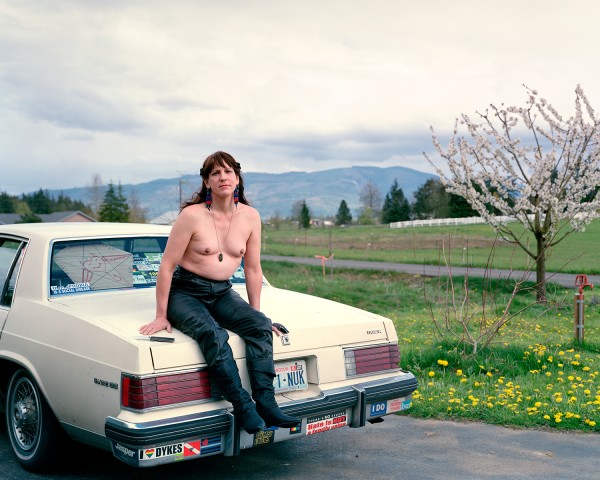

She found plenty of willing collaborators. Subjects chose where they would like to be photographed and which outfit they wanted to wear. One woman is shirtless, sitting on the trunk of her car with a field behind her, the car plastered in bumper stickers proclaiming “I heart dykes” and “Hate is not a family value” below her boot heels. In another work, a young trans man stands outside his house, the only clue to his queerness being a belt buckle that spells “BOY” across it in bold letters. (He told Landreth that, just like the belt, he could take his identity on and off.) Perhaps one of Landreth’s most unlikely pictures is of two Hassidic Jews seated at a kitchen table in their eclectic home, which includes a NO WAR sign and a hanging Kermit the Frog doll.

Ronni and Jo, 2005, Molly Landreth. Seattle, Washington.

Many of the photos feel intimate; looking at them, you feel as if you are intruding, and your eyes wander across the image cautiously. After all, by their very inclusion in the project each subject has outed him or herself. You are now complicit in the outing, and this fact binds you closer to the image and the subject staring back at you.

Looking through Landreth’s photographs, I feel a mounting response to my disquiet about queer representation. I don’t see myself in Landreth’s subjects, necessarily. In fact I’m not sure I’m supposed to. Instead, I wonder if a portrait can ever really capture a person, let alone an entire community. Particularly a community as fragmented and diverse as Queer America, dispersed throughout cities, suburbs, and small towns all over the country.

So I turn inward. I wonder which setting I would choose to be photographed in. Which clothes I would wear. Which emotion I would convey.

In my hypothetical portrait I sit in my own childhood living room, on the green couch that’s been there since before I was born, with a chain wrapped around my neck—an homage to Mapplethorpe. Only there is no one holding the chain. I’m alone, wearing jeans and a T-shirt, free to be queer, to be a queer, visible for the first time. The game is rigged, sure: Something is always left out of the frame. But I’m playing it. And I’m putting my whole self in the frame.

Sarah Coolidge is a writer living in the Bay Area. She is the online editor for the Center for the Art of Translation and an editorial assistant for Two Lines Press.

This essay is part of What Did Robert Mapplethorpe Teach Us?, a special package of stories from Zócalo Public Square.

*Lead photo: Andy, 2005, Molly Landreth. Oakland, California. All photos courtesy of Molly Landreth. All rights reserved.