It is a common complaint that the drive for traffic at news sites in the digital age has debased our political dialogue, turning a responsible press into a media scramble for salacious sound bites. But partisanship and scandal-mongering go way back in the American political tradition. And there was no internet to blame in 1793, the year an especially vicious and salacious newsman arrived on American shores and soon after set his sights on the founding fathers.

Despite efforts to unify the early United States around President George Washington, two factions quickly developed around his administration’s most articulate, forceful ideologues—Thomas Jefferson, who believed that the government governs best that governs least, and Alexander Hamilton, a Federalist who favored a robust national government that would have the power and revenues to do big things.

Hamilton and Jefferson realized that if they wanted their philosophies to have a practical impact, they would need political allies. But with no party system in the U.S., Hamilton and Jefferson turned to the only institutions that reached large numbers of men interested in public affairs: the newspapers.

Hamilton and Jefferson actively recruited newspaper editors who were sympathetic to their views. Those editors could not only spread the word, they could help readers figure out which candidates for office were on “their side.” In the absence of party labels, primaries, or advertising, the newspaper editors of the early Republic stepped into the vacuum and identified candidates who were “Jefferson men” or “Hamilton men.”

In this setting emerged one of the most vicious and dangerous of all the partisan writers and editors: the hard-drinking Scottish immigrant James Thomson Callender.

Callender seemed to have had a knack for finding trouble. Born in Scotland, he was charged with sedition and fled to America. He arrived in Philadelphia in May 1793—alone and nearly penniless. Within months he was offered a job reporting on the debates in Congress for the Philadelphia Gazette. He was quickly sacked, just around the time his family crossed the Atlantic and joined him. Struggling to make ends meet, he moved his wife and children onto Philadelphia’s docks and began drinking heavily. (At the time, most Americans drank what we would consider prodigious amounts of alcohol, from sunup to sunset. Even in that setting, those in the newspaper trade were known to have an especially strong thirst, and among them Callender’s was perhaps the most unquenchable of all.)

Callender fell in with Jefferson’s Anti-Federalists—they were called Republicans. In July 1797, Callender took on Hamilton, then the Treasury Secretary. In a lengthy pamphlet Callender revealed that Hamilton had transferred money to a convicted swindler named James Reynolds, insinuating that Hamilton and Reynolds were scheming to speculate in Treasury certificates, which were under Hamilton’s supervision.

Callender’s accusation forced Hamilton to reply, which he did, denying the charges of financial chicanery in hopes of preserving his public honor. But in order to explain the money transfers, Hamilton had to confess that he was having an affair with Reynolds’s wife, Maria. The money he was transferring to Mr. Reynolds was blackmail, intended to keep him from telling the story of Hamilton’s liaison with Mrs. Reynolds.

Callender didn’t think much of Hamilton’s explanation, and in a follow-up article he mocked Hamilton: “The whole proof … rests upon an illusion. ‘I am a rake, and for that reason I cannot be a swindler.’ ” Callender was prepared to believe that Hamilton was both a rake and a swindler. In any case, the damage was done. Politically, Hamilton was now ruined. Callender may have benefitted from a “leak” by one of Hamilton’s other rivals, James Monroe. But Callender was the messenger, the one who “broke” the story and made it a public scandal.

Hamilton’s disgrace naturally improved the standing of Jefferson, who encouraged Callender to pursue his slashing style of journalism. After all, Callender was laying waste to Federalists, which could only advance Jefferson’s political agenda. What could go wrong?

In the election of 1800, the Republican Jefferson defeated the Federalist John Adams (Washington’s successor as president), setting the stage for the first peaceful transfer of power between presidents who really disagreed with each other.

In the aftermath of victory, Jefferson faced many decisions, including the novel political question of how many positions on the federal payroll should be taken away from their Federalist occupants and turned over to Republicans. One of those who came calling on Jefferson after the election was none other than James Callender.

Callender must have felt that he had a strong claim to some of the spoils of office. After all, he had knee-capped Hamilton, the brightest star in the opposition camp, and he had even served time in jail for the Republican cause. Jefferson, however, was unmoved. Callender was hardly the well-born, talented sort that Jefferson thought should be serving in his administration, and the president sent him away empty-handed. Bad move.

Callender set out to get even. He promptly switched parties, revealing himself to be not a committed partisan but a hack, a mercenary who would attack either side—or both. In February 1802, Callender went into partnership with a Federalist editor in running the Richmond Recorder.

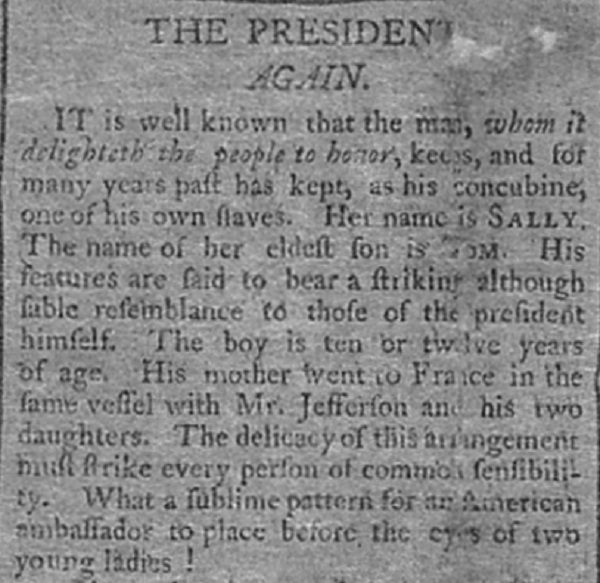

“The President, Again” published on September 1, 1802. By James Thomson Callender.

Callender assigned himself the job of bringing down Jefferson. Acting on the basis of rumors that he had picked up from anonymous sources, he let fly in print with the accusation that Jefferson had engaged in sexual relations with one of his slaves, later identified as Sally Hemings.

It is well known that the man, whom it delighteth the people to honor, [Jefferson] keeps and for many years has kept, as his concubine, one of his slaves. Her name is SALLY. The name of her eldest son is Tom. His features are said to bear a striking though sable resemblance to those of the president himself. … By this wench Sally, our president has had several children. There is not an individual in the neighbourhood of Charlottesville who does not believe the story, and not a few who know it.

Callender’s story was repeated in many Federalist papers, sometimes accompanied by lurid speculation about the “black Venus” at Monticello. In the two centuries since then, Callender’s assertion has become the focus of intense debate, both among Jefferson and Hemings family descendants and among historians. Recent DNA studies have tended to vindicate Callender’s reporting and indicate that the story is almost certainly true—that Jefferson was one founding father who found a way to father more than one branch of his family.

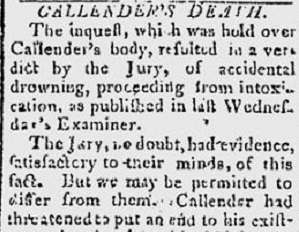

As for Callender, he was nearly finished. Having set the bar in the practice of scandal-mongering about the sex lives of presidents, his own life quickly went downhill. In December, he was the victim of a public beating and again succumbed to his great thirst. The following summer, in July 1803, during another of his periods of heavy drinking, Jimmy Callender was found in Virginia’s James River, floating facedown, dead at age 45.

From Examiner, July 27, 1803.

Meanwhile, Jefferson, burned by the partisan press he had helped develop, began having serious doubts about the virtues of a free press. In his private correspondence, Jefferson complained bitterly. By the time of his second inaugural address in March 1805, Jefferson was coming to view the press as a menace to decency itself.

“During the course of this administration,” he complained, “and in order to disturb it, the artillery of the press has been levelled against us, charged with whatsoever its licentiousness could devise or dare. These abuses of an institution so important to freedom and science, are deeply to be regretted.”

Plainly exasperated, he allowed himself the political luxury of speculating publicly about whether new state or federal laws might be needed to rein in the press. Like Donald Trump, he mused in public about the need to strengthen the libel laws.

No inference is here intended, that the laws, provided by the state against false and defamatory publications, should not be enforced; he who has the time, renders a service to public morals and public tranquility, in reforming these abuses by the salutary coercions of the law …

Even while still serving as president, Jefferson found time to engage in press criticism. In 1807, late in his second term, he corresponded with a Republican named John Norvell, who had written to the president to inquire about starting another new Republican newspaper. Jefferson saw the issue darkly:

Nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper. Truth itself becomes suspicious by being put into that polluted vehicle. … I will add, that the man who never looks into a newspaper is better informed than he who reads them …

Clearly, Jefferson had abandoned his earlier hope that newspapers would serve the nation as the guardians of the people’s liberty. His comments radiate a sense of an immense sadness and regret, coming from a man who fought for a free press but perhaps later wished that he had not, and who fought to secure his good name only to find it constantly in jeopardy in such a putrid and mendacious vehicle as a newspaper.

Chris Daly is a professor of journalism at Boston University. As a reporter for The Associated Press and the Washington Post, he covered presidential campaigns in 1988, 1992, and 1996. This essay is adapted from Covering America: A Narrative History of a Nation’s Journalism (UMass, 2012).

This essay is part of U.S. Presidential Elections Have Always Been Crazy, an Inquiry produced for What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.

*Lead photo illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo/Slate Magazine. Oil painting on canvas of Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull, 1806, Washington University Law School. The History of the United States for 1796, Snowden & M’Corkle. Interior photos courtesy of Library of Virgina.