Vice President Joe Biden, left, President Barack Obama, and former President George W. Bush, right, sing the national anthem at the end of the swearing-in ceremonies at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, Jan. 20, 2009. Photo by Ron Edmonds/Associated Press.

On Jan. 20, tens of millions of people will watch the pomp and spectacle of a uniquely American tradition. The hushed politicos in the pews of prayer service, the gleaming marching band brass on parade, the holy men and women delivering solemn invocations, the tuxes and gowns dancing their way through evening balls. And, of course, the next president of the United States of America, right hand up, left hand on the Bible, being sworn in for the highest office of the most powerful nation on the planet.

Yet all of the day’s formalities fail to cover up certain strains that often accompany this public ceremony. For alongside the pageantry, our inaugurations also expose some of the biggest tensions that define the American presidency—and show how our democracy has survived to repeat the ritual for the nation’s 45th commander-in-chief.

First and foremost, presidential inaugurations are, of course, markers of peaceful transitions of power—a method of handover that’s been more exception than the rule in the course of human history. They’re also celebrations for an elected office that is particularly American.

At the founding of the republic, monarchs led nearly every other nation. Even as democratic systems began to spread, most countries adopted parliamentary systems where legislatures chose prime ministers to head their governments (often alongside a ceremonial head of state, à la the U.K.’s Queen Elizabeth II, expected to hover above the partisan fray). But the U.S. presidency falls somewhere between—a head of government that assumes office on behalf of a political party, yet is expected to be a unifying head of state for all Americans. A strong singular executive who’s also balanced by two equally powerful government branches.

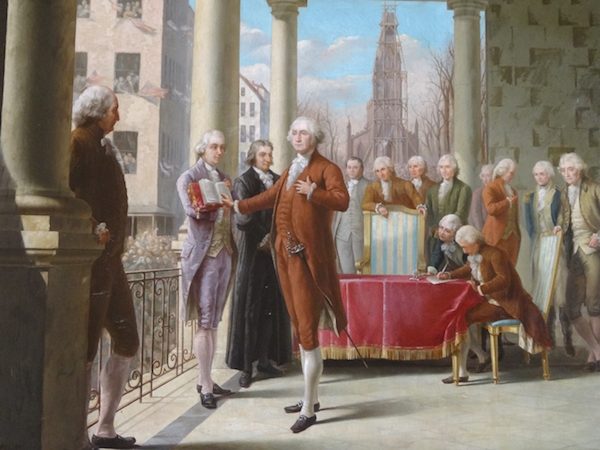

George Washington taking his oath of office as the first president of the United States. Courtesy of National Park Service.

As our first elected president, George Washington was conscious that he was setting precedent for this new position as head of a republic. He had already resigned his command of the Continental Army a few years earlier, despite calls for him to keep his wartime powers and rule the nation as a dictator or king. Yet he and his supporters also saw how his vast prestige could help support a fragile new government. So instead of simply taking his oath of office, the only Constitutionally-mandated element of an inauguration, they turned Washington’s ascension to the presidency into a show—one that helped publicly reconcile the compound, if not contradictory, roles bestowed on America’s top post.

The result blended the trappings of European monarchs they thought would give the office legitimacy with heavy nods to the presidency’s democratic foundations. In many ways, the inauguration looked like a coronation. His swearing in was turned to spectacle, complete with throngs of adoring lookers-on, invocations of the divine, and a gun salute.

But the new president also took care to keep the ceremony from looking too much like a crowning. Washington wore a plain brown suit to the affair, which was held at Federal Hall in the then-capitol of New York. He used his inaugural address (likely written with the help of James Madison) to praise the republican model of government, and to show humility at the task “to which the voice of my country called me.” And, of course, he drew attention to the president’s solemn pledge to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

Washington also set another powerful precedent eight years later: After two elected terms, he retired. His refusal to cling to control provided reassurance to those who feared the power of a single executive. It also set the stage for peaceful, regular transitions for centuries to come.

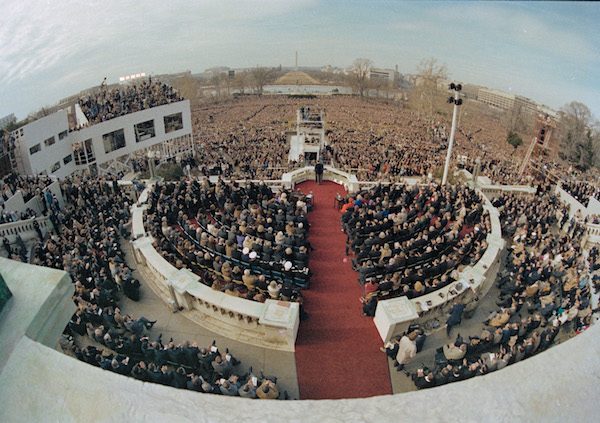

A wide angle view from the Capitol balcony as President Ronald Reagan, visible at center, addresses the nation following his swearing-in ceremony in Washington. Courtesy of Associated Press.

After Washington, most of America’s other presidents decided to keep up the pageantry of the inaugural inauguration too. In 1797, Oliver Ellsworth became the first chief justice to administer the oath of office when he swore in John Adams. Thomas Jefferson’s first inaugural was also the first to take place in the new capitol of Washington, and his second featured the first parade. James Madison had the first inaugural ball in 1809. And in 1981, Ronald Reagan shifted the ceremony from the Capitol’s East Portico to its West Front, allowing more of the public to witness the event from grounds of the National Mall.

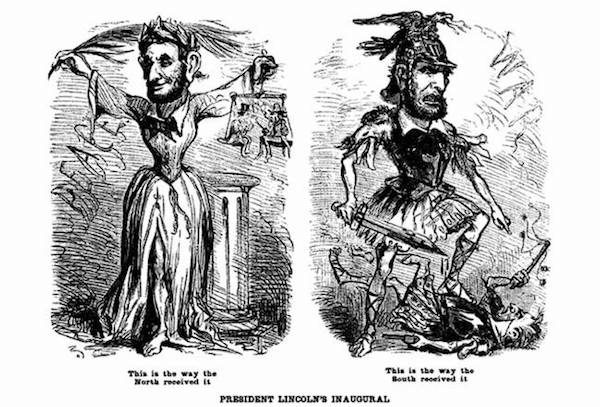

Beyond being celebrations of the American way of democracy, inaugurations also seek to provide a show of stability during contentious transitions. But divisiveness can still undermine democracy’s big day. Between Abraham Lincoln’s election and inauguration in 1861, seven southern states declared their secession from the Union and began forming the Confederate States of America. Rumors spread of plots to prevent Lincoln from reaching the capitol to ascend the presidency, so the president-elect disguised himself and took a night train through pro-slavery Baltimore to reach Washington on time. Artillery companies guarded Capitol Hill and sharpshooters lined his Pennsylvania Avenue route on Inauguration Day. Despite the drama, Lincoln used his first address to strike a conciliatory tone, telling Southerners, “We are not enemies, but friends.” It was all for naught. Within six weeks, the Civil War had begun. But America did have a properly sworn-in president at the helm.

Thomas Nast’s cartoon, published in the New York Illustrated News, March 23, 1861, captured how different audiences received Lincoln’s address. Courtesy of the Smithsonian.

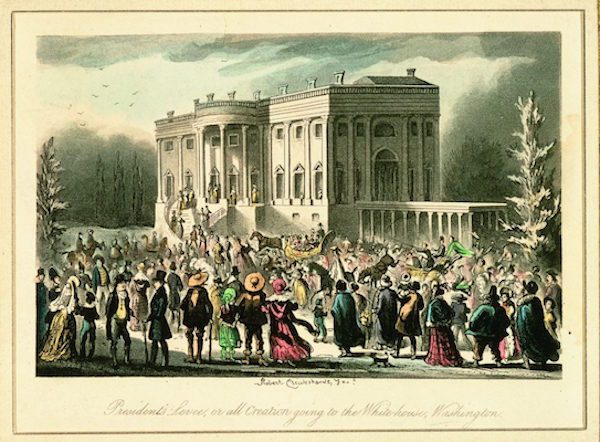

Even in the absence of a secessionist movement, partisanship can undercut aspirations for inaugurations to be celebrations of one united country, as opposed to one victorious political party. In 1829, Andrew Jackson’s new presidency marked a stark, populist departure from those of incumbent John Quincy Adams. Following a bitter election fight, his inauguration became more victory party than reconciliation. The outgoing president Adams didn’t show. But, fitting the new everyman order, a rowdy crowd of over 10,000 supporters did. The White House was so overwhelmed that servants reportedly started placing tubs of punch and ice cream on the lawn to draw well-wishers out of the mansion. Ronald Reagan’s 1981 inauguration also marked a dramatic, though less raucous, ideological shift. Though he included a bit of bipartisan language in the day’s address, it’s best remembered for political lines like, “In the present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

Famously, Jackson threw an inauguration party at the White House where guests refused to leave and to be lured outside the building by tubs of ice cream and whisky punch. Engraving by Robert Cruikshank, sometimes referred to as Isaac Robert Cruikshank. Courtesy of White House Collection.

Yet just as many inaugurations are remembered for presidents-elect who tried to smooth bumpy handoffs. In 1801, Thomas Jefferson, who was the first president to come from a different party from that of his predecessor, tried to strike a unifying tone in his inaugural address, declaring, “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

More recently, Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama negotiated what is considered to be the best-managed presidential transition—and did so amid an economic crisis, post-9/11 national security concerns, two ongoing wars, and a particularly historic handover. Larger forces also brought together the outgoing Herbert Hoover and incoming Franklin D. Roosevelt for the good of the country. Though the two men openly loathed each through their rocky transition, they kept up appearances by sharing a lift to the new president’s inauguration. Hoover mostly scowled as FDR tipped top hat to the crowds. But he honored the tradition that, with rare exception (assassination, resignation, natural death, and a few 19th century cases of animosity), the outgoing president has always made some sort of symbolic show on Inauguration Day. It’s perhaps the ceremony’s most powerful, if occasionally awkward, symbol of the peaceful passage of power.

The Rockettes perform during the Celebration of Freedom Concert on the Ellipse on Jan. 19, 2005. The Rockettes have been assigned to dance at President-elect Donald Trump’s inauguration this month. Photo by Chris Gardner/Associated Press.

Richard M. Skinner teaches political science at Johns Hopkins and George Washington Universities.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.