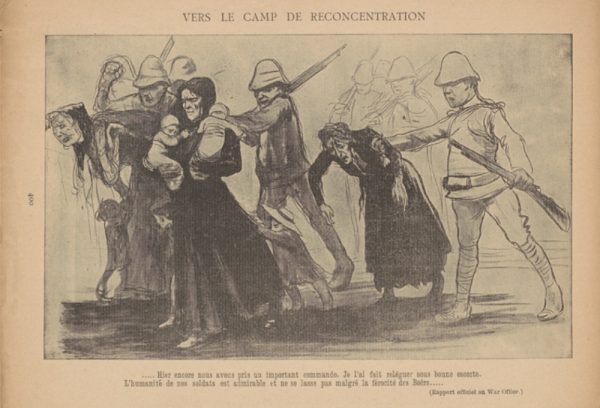

An illustration by cartoonist Jean Veber depicts British Army troops rounding up South African Boer civilians. Image courtesy of the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection.

The earliest modern experiment in detaining groups of civilians without trial was launched by two generals: one who refused to bring camps into the world, and one who did not.

Battles had raged off and on for decades over Cuba’s desire for independence from Spain. After years of fighting with Cuban rebels, Arsenio Martínez Campos, the governor-general of the island, wrote to the Spanish prime minister in 1895 to say that he believed the only path to victory lay in inflicting new cruelties on civilians and fighters alike. To isolate rebels from the peasants who sometimes fed or sheltered them, he thought, it would be necessary to relocate hundreds of thousands of rural inhabitants into Spanish-held cities behind barbed wire, a strategy he called reconcentración.

But the rebels had shown mercy to the Spanish wounded and had returned prisoners of war unharmed. And so Martínez Campos could not bring himself to launch the process of reconcentración against an enemy he saw as honorable. He wrote to Spain and offered to surrender his post rather than impose the measures he had laid out as necessary. “I cannot,” he wrote, “as the representative of a civilized nation, be the first to give the example of cruelty and intransigence.”

Spain recalled Martínez Campos, and in his place sent general Valeriano Weyler, nicknamed “the Butcher.” There was little doubt about what the results would be. “If he cannot make successful war upon the insurgents,” wrote The New York Times in 1896, “he can make war upon the unarmed population of Cuba.”

Civilians were forced, on penalty of death, to move into these encampments, and within a year the island held tens of thousands of dead or dying reconcentrados, who were lionized as martyrs in U.S. newspapers. No mass executions were necessary; horrific living conditions and lack of food eventually took the lives of some 150,000 people.

These camps did not rise out of nowhere. Forced labor had existed for centuries around the world, and the parallel institutions of Native American reservations and Spanish missions set the stage for relocating vulnerable residents away from their homes and forcing them to stay elsewhere. But it was not until the technology of barbed wire and automatic weapons that a small guard force could impose mass detention. With that shift, a new institution came into being, and the phrase “concentration camps” entered the world.

When U.S. newspapers reported on Spain’s brutality, Americans shipped millions of pounds of cornmeal, potatoes, peas, rice, beans, quinine, condensed milk, and other staples to the starving peasants, with railways offering to carry the goods to coastal ports free of charge. By the time the USS Maine sank in Havana harbor in February 1898, the United States was already primed to go to war. Making a call to arms before Congress, President William McKinley said of the policy of reconcentración: “It was not civilized warfare. It was extermination. The only peace it could beget was that of the wilderness and the grave.”

But official rejection of the camps was short-lived. After defeating Spain in Cuba in a matter of months, the United States took possession of several Spanish colonies, including the Philippines, where another rebellion was underway. By the end of 1901, U.S. generals fighting in the most recalcitrant regions of the islands had likewise turned to concentration camps. The military recorded this turn officially as an orderly application of measured tactics, but that did not reflect the view on the ground. Upon seeing one camp, an Army officer wrote, “It seems way out of the world without a sight of the sea,—in fact, more like some suburb of hell.”

In southern Africa, the concept of concentration camps had simultaneously taken root. In 1900, during the Boer War, the British began relocating more than 200,000 civilians, mostly women and children, behind barbed wire into bell tents or improvised huts. Again, the idea of punishing civilians evoked horror among those who saw themselves as representatives of a civilized nation. “When is a war not a war?” asked British Member of Parliament Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman in June 1901. “When it is carried on by methods of barbarism in South Africa.”

Far more people died in the camps than in combat. Polluted water supplies, lack of food, and infectious diseases ended up killing tens of thousands of detainees. Even though the Boers were often portrayed as crude people undeserving of sympathy, the treatment of European descendants in this fashion was shocking to the British public. Less notice was taken of British camps for black Africans who had even more squalid living conditions and, at times, only half the rations allotted to white detainees.

The Boer War ended in 1902, but camps soon appeared elsewhere. In 1904, in the neighboring German colony of South-West Africa—now Namibia—German general Lothar von Trotha issued an extermination order for the rebellious Herero people, writing “Every Herero, with or without a gun, with or without cattle, will be shot.”

Tanauan reconcentrado camp, Batangas, the Philippines, circa 1901. Image courtesy of University of Michigan Digital Library Collection.

The order was rescinded soon after, but the damage inflicted on indigenous peoples did not stop. The surviving Herero—and later the Nama people as well—were herded into concentration camps to face forced labor, inadequate rations, and lethal diseases. Before the camps were fully disbanded in 1907, German policies managed to kill some 70,000 Namibians in all, nearly exterminating the Herero.

It took just a decade for concentration camps to be established in wars on three continents. They were used to exterminate undesirable populations through labor, to clear contested areas, to punish suspected rebel sympathizers, and as a cudgel against guerrilla fighters whose wives and children were interned. Most of all, concentration camps made civilians into proxies in order to get at combatants who had dared defy the ruling power.

While these camps were widely viewed as a disgrace to modern society, this disgust was not sufficient to preclude their future use.

During the First World War, the camps evolved to address new circumstances. Widespread conscription meant that any military-age male German deported from England would soon return in a uniform to fight, with the reverse also being true. So Britain initially focused on locking up foreigners against whom it claimed to have well-grounded suspicions.

British home secretary Reginald McKenna batted away calls for universal internment, protesting that the public had no more to fear from the great majority of enemy aliens than they did from “from the ordinary bad Englishman.” But with the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 by a German submarine and the deaths of more than a thousand civilians, British prime minister Herbert Henry Asquith took revenge, locking up tens of thousands of German and Austro-Hungarian “enemy aliens” in England.

The same year, the British Empire extended internment to its colonies and possessions. The Germans responded with mass arrests of aliens from not only Britain but Australia, Canada, and South Africa as well. Concentration camps soon flourished around the globe: in France, Russia, Turkey, Austro-Hungary, Brazil, Japan, China, India, Haiti, Cuba, Singapore, Siam, New Zealand, and many other locations. Over time, concentration camps would become a tool in the arsenal of nearly every country.

In the United States, more than two thousand prisoners were held in camps during the war. German-born conductor Karl Muck, a Swiss national, wound up in detention in Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia after false rumors that he had refused to conduct “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Unlike earlier colonial camps, many camps during the First World War were hundreds or thousands of miles from the front lines, and life in them developed a strange normalcy. Prisoners were assigned numbers that traveled with them as they moved from camp to camp. Letters could be sent to detainees, and packages received. In some cases, money was transferred and accounts kept. A bureaucracy of detention emerged, with Red Cross inspectors visiting and making reports.

By the end of the war, more than 800,000 civilians had been held in concentration camps, with hundreds of thousands more forced into exile in remote regions. Mental illness and shattered minority communities were just two of the tolls this long-term internment exacted from detainees.

Nevertheless, this more “civilized” approach toward enemy aliens during the First World War managed to rehabilitate the sullied image of concentration camps. People accepted the notion that a targeted group might turn itself in and be detained during a crisis, with a reasonable expectation to one day be released without permanent harm. Later in the century, this expectation would have tragic consequences.

Yet even as the First World War raged, the camps’ bitter roots survived. The Ottoman government made use of a less-visible system of concentration camps with inadequate food and shelter to deport Armenians into the Syrian desert as part of an orchestrated genocide.

And after the war ended, the evolution of concentration camps took another grim turn. Where internment camps of the First World War had focused on foreigners, the camps that followed—the Soviet Gulag, the Nazi Konzentrationslager—used the same methods on their own citizens.

In the first Cuban camps, fatalities had resulted from neglect. Half a century later, camps would be industrialized using the power of a modern state. The concept of the concentration camp would reach its apotheosis in the death camps of Nazi Germany, where prisoners were reduced not just to a number, but to nothing.

The 20th century made General Martínez Campos into a dark visionary. Refusing to institute concentration camps on Cuba, he had said, “The conditions of hunger and misery in these centers would be incalculable.” And once they were unleashed on the world, concentration camps proved impossible to eradicate.

Andrea Pitzer is a journalist who delves into lost and forgotten history. She is the author of One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps.