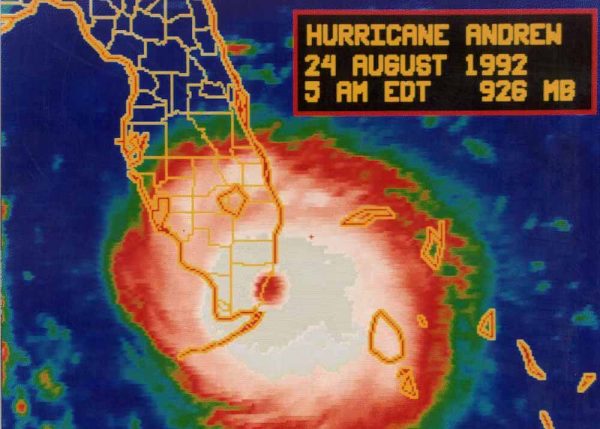

Hurricane Andrew making landfall in Miami in 1992. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

After school, whenever I walked into my family’s home in Davie, Florida, I was always reminded of 1992’s Hurricane Andrew, which decimated nearly 64,000 homes some 60 miles away in the city of Homestead. Andrew—all Floridians are on a first name basis with their hurricanes—still lived on via the duct tape my uncle had applied to our jalousie windows. Even after the tape was removed, a large X of residue remained that my mother never bothered to scrub off.

Two things are funny about this: First, I didn’t actually experience Andrew, because I didn’t move to Florida until 1993. Second, that was the extent of hurricane preparations back then—duct tape to be sure that if the windows shattered, the glass would stick together, instead of splintering into tiny and dangerous little pieces. When you’ve grown up with hurricanes, their memories—like the tape residue—never quite go away.

My first real hurricane was Erin in 1995. Then nine years old, I had no idea what to expect, but figured that all hurricanes were the same and this one would tear my house apart. So I took matters into my own hands. I got that green plastic mover’s wrap you can find at U-Haul, fully wrapped the 13-inch CRT television I’d negotiated having in my bedroom, and put all of my books, Barbies, and beanie babies in plastic storage bins.

During Erin, every window in our home was covered with plywood, so inside the house it felt like it was 2 a.m. even during the day. I plopped down to watch the living room TV, but all broadcasts had the same information on loop until the next National Hurricane Center forecast was released (every 6 hours). After several hours of this, I decided that my house was not going to flood and that I could unwrap my bedroom television and go back to watching The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

I don’t mean to be flip—I know that hurricanes can kill people and destroy entire regions, and, when response and relief are slow to arrive, the aftermath of these storms can be even deadlier, as Puerto Rico is tragically experiencing right now.

The author as a child in front of her family home in Davie, Florida, October 28, 1994. Photo courtesy of Dulce Vasquez.

But for those who have lived in hurricane-prone places, these epic disasters can come to feel routine. For me ever since Erin, hurricanes have been business as usual to me. Floridians rarely flinch at anything weaker than a Category 3. You go through the motions: put plywood on the windows, get enough water and non-perishable goods, fill every car you own with gas to the brim, and hope for the best.

As a kid, I always hoped the hurricanes would come during the week so school would get cancelled. If we were really lucky (which I was a few times), the storm would hit on a test day and I’d have a few extra days to study.

The familiarity of the pre-hurricane procedure was, in its way, comforting. My family would sit on the couch and flip between The Weather Channel and Spanish news. My mom would go up to the TV and point to all possible trajectories, always deciding that we’d be a direct hit. My dad would then reason with her. But we were all experiencing it together.

The feeling that this was a holiday continued during the lull after the storm passed through. It almost feels like Christmas morning, where everything is quiet, and no one is in the streets yet and riding their bicycles.

The storms, like birthdays or holidays, eventually become part of the way you remember life.

In 2004, there was Ivan, which made me late for my first day of college in Chicago. The airport didn’t reopen until an hour after my flight was supposed to take off. Similarly, Ernesto in 2006 made me one week late to my study-abroad program in Paris.

I remember Katrina. My mother’s prediction of our home being a direct hit finally came true in August 2005 when the eye of Katrina made its first landfall just north of Miami as “only” a category 1. It was nothing compared to what happened in Louisiana, but it still managed to leave a million Floridians without power and cause $630 million dollars’ worth of damage.

In the lull after that storm, sitting in my bedroom, I managed to write to one of my dorm mates from college, who lived in New Orleans. I warned that as a category 1 storm, it’d been very powerful, and hoped he’d be careful. He wrote back to confirm he and his family had evacuated to north Florida. When we got back to school a few weeks later he let us know that his home was under 6 feet of water and was a total loss.

That same season was when I experienced my first hurricane from afar. Wilma ripped through Florida later in 2005. It was one of the latest-forming storms I can remember, hitting in late October. Comfortably welcoming fall in Chicago, I talked with my parents every day. They called to say they were safe and had a generator to power the fridge. Within a few days, my dad had run hundreds of feet of extension cords to power our three neighbors’ refrigerators. It took three weeks for their power to get restored.

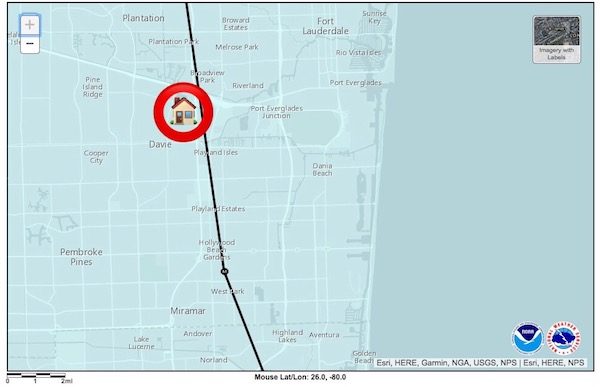

A map showing the author’s family home during Hurricane Irma, September 6, 2017. Photo courtesy of Dulce Vasquez.

I still visit often, but I haven’t lived in Florida since 2005. As it happens, no major hurricane since Wilma in 2005 had made direct landfall in Florida, until this year. Over the last 12 years, my family had dealt with warnings and evacuations, and my parents, instead of scurrying to Home Depot for plywood, replaced those outdated jalousie windows with some double paned windows with beautiful colonial grilles. To protect them, they invested their tax refunds on accordion shutters that take no more than 5 minutes per window to close.

But Irma brought the hurricanes back home. From Los Angeles, where I live, I started tracking Irma as soon as it became a category 5 storm. On Monday, my mom texted “Looks like pinche Irma is coming.” Harvey had just destroyed Houston, and this was poised to be an even stronger hurricane, so there I was again, every six hours looking for the next National Hurricane Center forecast update.

On Tuesday, I asked my mom if they wanted to evacuate, and volunteered to book their flights. She said they’d wait and make a call on Thursday. On Wednesday, I sent my mom a graphic of the latest trajectory, which showed Irma blowing directly through their house. I asked again if they wanted to evacuate.

On Thursday my mom said she wanted to evacuate but my dad didn’t want to. My anxiety and frustration grew. That night I had a dream that the roof of our home tore off. On Friday, I took action and told mom that the safest place in the house was in the bathroom (most inner, central place in the house, without windows). I wasn’t sure if that’s true or not, but it made me feel better.

On Saturday, my aunt, uncle, and cousin came to my parents’ house—they live in a mobile home and those are always unsafe. Curfew started at 4 p.m.

On Sunday, as soon as I woke up and still in bed, I texted my mom to check in, but my iMessages were not going through. That meant they lost power and/or cell service. I started to panic. I texted everyone else in the house: Mom, Dad, brother, cousin, aunt. Nothing. Finally, after what seemed like the longest 20 minutes of my life, a message finally came through. All were safe. Relief.

Through the whole process, every ounce of me wanted to be there, in the storm with my family.

Dulce Vasquez is director of strategic partnerships at Arizona State University and the former managing director at Zócalo Public Square.