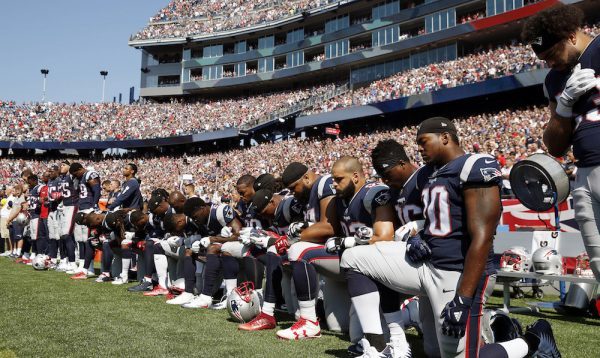

Several New England Patriots players kneel during the national anthem before an NFL football game against the Houston Texans on September 24, 2017. Photo by Michael Dwyer/Associated Press.

President Donald Trump did not say, “Yo’ mama!” in front of a partisan Huntsville, Alabama audience. But he might as well have because that is what athletes heard directed at them.

Perhaps without even realizing it, the president had engaged in an age-old tradition of playing the dozens, the term for an African American game involving the exchange of insults before an audience. Or did he just think he’s playing the politics of distraction-as-usual, and playing to his base?

Whether he knew it or not, the bully, Trump, went after one group that has spent their lives beating bullies: black male athletes. And, in this new-age mix of politics and sports, these men also possess a pulpit as powerful as the president’s and a combined Twitter following that far exceeds his. Had he met his match?

It remains an open question whether Trump understood the game he had started to play. For one thing, his tone was off. On playgrounds you rarely hear as circuitous an insult as “son of a bitch,” the phrase Trump used when urging NFL owners to fire players who protested during the national anthem.

No, the dozens are more direct.

“Your mother is a bitch” is what a truly street-hardened president would have said to the players, as he anticipated the return blow and stood ready to dish out more. But Trump has clearly stumbled into this unfamiliar territory. He was just using the so-called genuine language that has brought him political success.

Meanwhile, the athletes’ response to Trump on social media was massive and direct. None that I saw took the traditional path of going after his mama, but sometimes that phase is skipped, in favor of going straight to the source spewing the dozens, delivering a punch in the face. In that vein, Buffalo Bills running back LeSean McCoy just tweeted the unambiguous: “asshole.” LeBron James of the NBA’s “u bum” tweet at Trump was viewed by more people than any single tweet by the president himself.

Among the many ironies of this exchange is the unity it has brought, if only momentarily, between professional players and team owners, between player unions and the leagues. The moment goes beyond football. Basketball players have been brought together by Trump’s decision to rescind his invitation to the NBA champion Golden State Warriors to visit the White House. Baseball players have joined the protests, and golfers, tennis players (including the icon Billie Jean King), and even the NASCAR driver Dale Earnhardt, Jr. have tweeted in favor of the right for peaceful protest.

Although it’s new for a president to engage (consciously or not) in the dozens, athletes are also facing new expectations and responsibilities. We are witnessing many of our athletes coming of age to fulfill a new requirement of contemplation and intellectualism. They need an opinion, whether they choose to express it or not. They need to know what they are going to do or not do.

President Trump greets the Super Bowl champion New England Patriots. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

LeBron James has been the leader in this new era; he spoke out during the Trayvon Martin homicide back in 2012. But today, the political decisions facing athletes are more complicated, and the expectations for fast and meaningful responses have been raised.

The difficulties of navigating this athletic-political minefield were exemplified by two players on the same team. When the Pittsburgh Steelers decided to stay in the locker room during the national anthem last Sunday, an offensive lineman and former Army Ranger, Alejandro Villanueva, chose to come out alone and salute the flag. Ben Roethlisberger, the team’s star quarterback, stayed in the locker room with the team. They both later expressed regret for making their decisions separately, which suggested a lack of unity. Politics, like football, is a team sport.

Political pressure also falls on the team owners, who were the other group targeted in the Alabama speech, as the president told them how to run their businesses. This is the rich person’s equivalent of the dozens, and no doubt the thought bubbles arising from this group of football billionaires and millionaires said, “This guy was one of us, and not even as rich as me, and he’s getting in our business?”

The New England Patriots owner, Robert Kraft, who befriended Trump and backed his campaign, said he was “deeply disappointed” at Trump’s comments, and clearly by his lack of reciprocity. He wasn’t the only owner who experienced presidential betrayal.

Trump’s attacks were news, and not just because Trump is always news. Most of the time, sports are about the games themselves. Political protest has been a lesser concern, usually a one-off when it touches sports—a boycott, an arm band, or a political punch added to a Hall of Fame speech. When sport has been invoked in politics it’s rarely been about whether athletes are pulling the nation apart, but instead it’s generally been related to the need for national healing. (An exception is the fist-extended protests of John Carlos and Tommie Smith on the medal stand at the 1968 Olympics).

One of the most understudied exchanges between sports and politics took place between then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Commissioner of Baseball Kenesaw Mountain Landis in 1942. In what has come to be known as the “green light” letter, Roosevelt advised Landis that the games should be played during World War II. The president’s logic was that in time of war, the American workers “ought to have a chance for recreation and for taking their minds off their work even more than before.” Landis followed the presidential advice, and Major League Baseball was played throughout the war.

In a similar spirit, the NFL decided to play their Sunday games two days after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, although the NFL commissioner, Pete Rozelle, would call it one of his biggest regrets. (In retrospect, he might have listened to one owner, who sought a court order to stop play).

When the Gulf War began, 10 days before the 25th anniversary Super Bowl in Tampa in 1991, it made for a memorable juxtaposition of football and military display. That created a charged atmosphere for Whitney Houston’s famously stirring rendition of the national anthem, which concluded with a flyover by four F-16 fighter jets.

But sometimes sports gives way. After the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001, the NFL postponed the games that were scheduled to be played on the following Sunday. For a brief period all planes were still grounded in the United States and the players, like all other Americans, had mixed feelings about travel even when flights resumed.

Even after real tragedies, moments of national unity are short-lived. Today’s Donald Trump-inspired unity won’t last long. The athletes and the owners will soon head back to their respective corners, at least until another unifying “your mama” moment brings them together again.

Maybe it will be Trump, the distractor in chief, who provides that new moment, as he blasts away at others to take our attention away from the racism and political problems that surround him. As LeBron James observed recently, the president doesn’t seem to recognize how he might bring people together, if he so chooses. “He doesn’t understand the power that he has for being the leader of this beautiful country,” tweeted James. “He doesn’t understand how many kids, no matter their race, look up to the President …”

In this upside-down world of politics and sports, maybe Trump will own up to his own productive divisiveness. He could channel the great basketball player Charles Barkley, who famously declared in a TV commercial, “I am not a role model.”

Kenneth L. Shropshire is the Adidas Distinguished Professor of Global Sport and CEO of the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University and a Professor Emeritus at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.