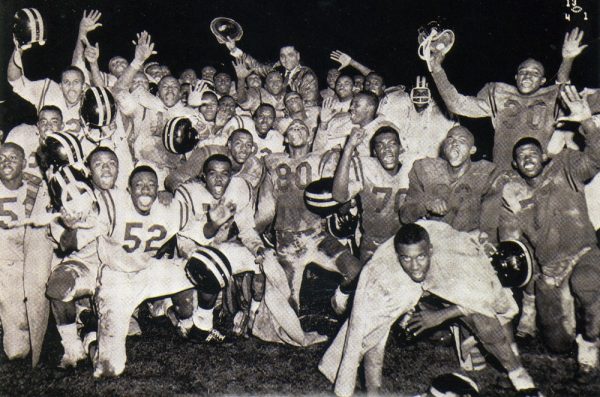

Austin Anderson’s football team finished its 1961 season with a 20-13 state championship win at Jeppesen Stadium. Photo by Leroy Bookman.

As a sportswriter, during my visits I instinctively gravitated towards athletics venues. I would drive by the crumbling Astrodome, dwarfed by the gigantic NRG Stadium, home of the NFL’s Houston Texans; the Houston Astros’ new downtown baseball playground, Minute Maid Park; Rice University Stadium, the site of Super Bowl VIII in 1974, still holding up near the Medical Center.

Nothing about the changes in those venues fazed me. Houston’s dynamic progress was to be expected. But I was disturbed, as I made my rounds one summer morning in 2015, to see a shiny new stadium for University of Houston Cougars football. I entered Third Ward, the city’s historic African-American cultural hub, drove past the Cougars’ new den for the first time, and was so shaken by the sight that I narrowly avoided veering into oncoming traffic.

Something was terribly wrong. This was not just any new testament to collegiate athletic funding. This was a state-of-the-art, gentrified grave marker, covering—no, unashamedly hiding—a significant monument to Houston’s African-American history, now bulldozed to oblivion. Underneath this 60-acre plot, my hometown had buried a place called Jeppesen Stadium. Along with it, Houston silenced the athletic ghosts of a Jim Crow past that prevailed, for decades, throughout Texas.

Segregation had necessitated the formation, in 1920, of the Prairie View Interscholastic League (PVIL), the governing body for black high school athletics, academic, and music competitions in Texas. The University Interscholastic League, which oversaw the same activities for white students, denied membership to African-American schools. So the PVIL became the guiding force behind African-American high school gridiron action in the region. Its football was highly competitive and thrilling to watch.

In Houston, from the 1940s through 1967, the league’s Wednesday and Thursday night football games took place at Jeppesen, the school district’s public football facility. Jeppesen was the last and most visible connection to a past that saw Texas’s African-American community defy a racist system and produce some of the best high school coaches, athletes, and teams in the state’s football-mad history. For me, it was also an enduring link to my adolescence.

Jeppesen had none of the engaging architectural features of its successor, the new University of Houston stadium; it was just a dirty beige-colored concrete edifice. But even if it was homely, Jeppesen had glamor. Houston was the PVIL’s largest market, and the league fostered cultural and community pride. Jeppesen drew fans from black enclaves—Fifth Ward, Fourth Ward, Third Ward, Kashmere Gardens, Sunnyside, Acres Homes, and the Gulf Coast—to cheer for their teams, which included great players like Bubba Smith, Eldridge Dickey, Mel Farr, Gene Washington, Otis Taylor, and Warren Wells.

As many as 40,000 fans gathered in Jeppesen’s stands for the annual Thanksgiving Turkey Day Classic game between heated crosstown rivals Jack Yates and Phillis Wheatley High Schools. Attendees dressed in their Sunday best, and then some, for the social event of the season. The day included pre- and post-game events, parades, alumni and family breakfasts and dinners, and flashy halftime marching band performances. Yates fans still talk about the 1958 halftime show, when Miss Yates and her court arrived in a helicopter. It landed on the 50-yard line to a deafening roar from the crowd.

A number of PVIL players went on to dominate professional football. Six of its alumni were inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, including “Mean Joe” Greene (from Temple Dunbar High School), defensive back Dick “Night Train” Lane (from Austin Anderson High School), and safety Ken Houston (from Lufkin Dunbar High School). In 1965, wide receiver Jerry LeVias, from Hebert High School in Beaumont, became the first African-American football scholarship player in the old Southwest Conference when he decided to attend Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

Charles “Bubba” Smith, at 6 feet 7 inches, terrorized PVIL opponents in the early 1960s as a lineman at Charlton-Pollard High School in Beaumont, east of Houston, and later became one of the most feared defensive players in college football history at Michigan State, and in the National Football League with the Baltimore Colts. In 1992, Smith recalled playing in the PVIL to a Houston Chronicle writer: “You’re talking about people who could righteously play the game. None of the teams were diluted back then. Everyone on the field could play. If you blink, they were gone. It was more physical and tougher. And it always meant something if you could outrun somebody because everybody could run.”

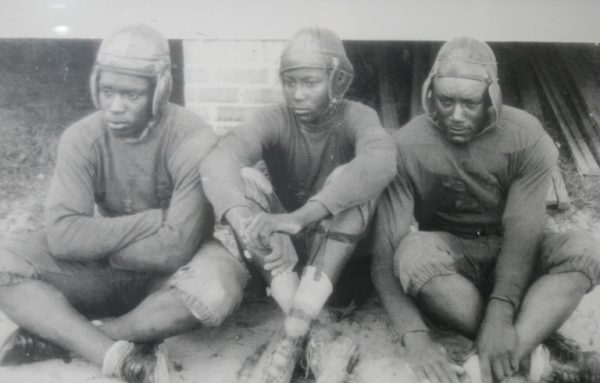

The Prairie View Interscholastic League governed athletic, academic, and music competitions for black high schools in Texas from 1920-1970. These athletes played football during the 1930s. Photo courtesy of PVILCA.

Case in point: Cliff Branch was a four-time All-Pro receiver and three-time Super Bowl champion with the Oakland Raiders, and a world-class sprinter for the Colorado Buffaloes. At Worthing High School in Houston, he was a two-time PVIL 3-A state sprint champ and the first schoolboy in Texas history to run the 100-yard dash in 9.3 seconds, a record that stood only as long as it took the very next heat, for 2-A boys, to conclude. When it did, Wichita Falls Washington speedster Reggie Robinson was the new record-holder, breezing to a 9.1 second finish.

That kind of speed only mattered in athletic contests. None of the PVIL players could outrun racism and segregation, the wedges that maintained the misguided myth of white supremacy even in athletics. While there would be no shortage of newspaper and magazine articles, books, and movies about high school football in Texas, none focused on the teams and players from the PVIL. Few on the outside were willing to acknowledge the abundance of talent bursting from the under-funded schools of the “Negro League,” or the “Colored League,” as some called it in polite company. One former PVIL player spoke with disdain about the term “Friday Night Lights,” explaining, “That’s white folks.”

“There was the black side of town and the white side, and you just dealt with what was laid out there for you,” Smith would add. “You didn’t have time to think, ‘Why can’t I do that, or why is it like that?’ Sometimes I think a large part of my life was lost by that. But you could always show what you had on the football field.”

And there was so much to show. The PVIL created lasting passionate school rivalries, and instilled confidence in its athletes and students. Teachers and coaches were short on resources but eager to be mentors, and accepted the task of preparing black children for citizenship in an environment that neither welcomed nor encouraged them.

The league’s relationship with historically black colleges fortified it. Black colleges provided the only options in the South for African-Americans seeking higher education, and Texas had several HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities), including Prairie View, Wiley, and Bishop. Black coaches and teachers had earned degrees at black colleges—often starring as players, then returning home to work in black high schools. In turn, coaches would send their best players to their collegiate alma maters, creating a string of black men guiding young black boys to adulthood.

“I knew all the mommas and poppas,” Joe Washington Sr., father of former Oklahoma Sooners and NFL running back Joe Washington, recalled from his days as head coach at Bay City’s Hilliard High School and then at Port Arthur Lincoln High School. “They used to tell me, ‘Coach Washington, take him and do what you have to do, just don’t kill him.’ ”

Some look at the loss of those nurturing relationships as a tragedy of integration, which brought about the fall of the PVIL, the closing of black high schools, and erosion in black communities.

In the fall of 1967, black and white schools competed against each other for the first time, previously all-white programs added black players, and Texas could legitimately claim playing the best high school football in the country. White coaches had quietly salivated, waiting for the moment when they could welcome all of the most talented players to their programs, and the newcomers did not disappoint. The infusion of black athletes to UIL teams made instant winners of longtime losing teams, allowing coaches to gloat about their new black superstar: “I got me one.”

I graduated from Worthing in the spring of 1967, just as the PVIL and UIL “merged.” It was closer to a hostile takeover. As the PVIL began shutting down, so did most of its member schools, although some smaller schools lingered for another three seasons in the league. (From a high of 500, only eight former PVIL schools remain in operation today.) Successful PVIL coaches with state championships under their belts lost jobs. Other coaches retired or left the profession rather than take demotions to work as assistants on predominantly white staffs.

At first, I didn’t appreciate the sea change that integration would deliver to the PVIL. I thought it was great that black players would finally get a wider audience, and get to compare skills with white players. But when I returned that fall for our homecoming football game, against a white team in a different setting, I felt wistful and restless. The new stadium lacked the Jeppesen atmosphere. I left at halftime, thinking what PVIL folks surely had already figured out.

“You just have to have integration, we knew it all along and we wanted it,” said the late Luther Booker, a former head coach at Yates. “But you miss those days because it was such a high. It affected the black community. It was an electrifying time. There’s nothing like it now. And maybe there never will be.”

Certainly, there will be no more beacons like Jeppesen.

Michael Hurd is a Houston native and the author of Thursday Night Lights, the Story of Black High School Football in Texas, which will be released by University of Texas Press in October. He is a former sportswriter for USA Today, the Austin American-Statesman, The Houston Post, and Yahoo Sports. Currently, he is director for Prairie View A&M University’s Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a partnership of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Zócalo Public Square.