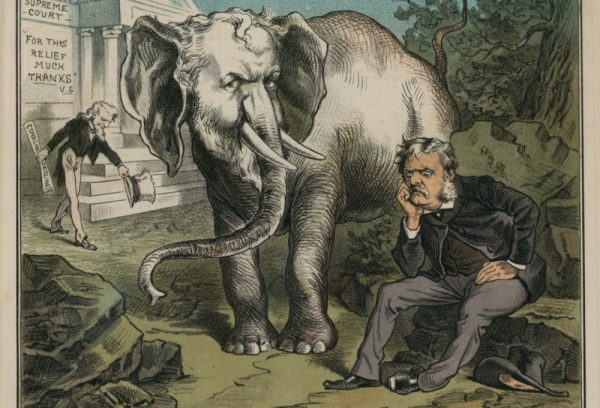

A Puck magazine cartoon expresses the fear that with Chester Arthur as president, U.S. Senator Roscoe Conkling, the all-powerful boss of the New York Republican machine, would be running the country. Art courtesy of Library of Congress.

But at least one man was transformed by the presidency: Chester Alan Arthur. Arthur’s redemption is all the more remarkable because it was spurred, at least in part, by a mysterious young woman who implored him to rediscover his better self.

Arthur, the country’s 21st president, often lands on lists of the most obscure chief executives. Few Americans know anything about him, and even history buffs mostly recall him for his magnificent mutton-chop sideburns.

Most visitors to Arthur’s brownstone at 123 Lexington Avenue in New York City are there to shop at Kalustyan’s, a store that sells Indian and Middle Eastern spices and foods—not to see the only site in the city where a president took the oath of office. Arthur’s statue in Madison Square Park, erected by his friends in 1899, is ignored. But Arthur’s story of redemption, which illustrates the profound impact that the U.S. presidency can have on a person, deserves to be remembered.

Arthur was born in Vermont in 1829, the son of a rigid abolitionist preacher. Even in the North, abolitionism was not popular during the first decades of the 19th century, and Arthur’s father—known as Elder Arthur—was so outspoken and uncompromising in his beliefs that he was kicked out of several congregations, forcing him to move his family from town to town in Vermont and upstate New York.

Shortly after graduating from Union College in Schenectady, Arthur did what many ambitious young men from the hinterlands do: He moved to New York City. Once there, he became a lawyer, joining the firm of a friend of his father’s, who was also a staunch abolitionist.

And so he started down an idealistic path. As a young attorney, Arthur won the 1855 case that desegregated New York City’s streetcars. During the Civil War, when many corrupt officials gorged themselves on government contracts, he was an honest and efficient quartermaster for the Union Army.

But after the war Arthur changed. Seeking greater wealth and influence, he became a top lieutenant to U.S. Senator Roscoe Conkling, the all-powerful boss of the New York Republican machine. For the machine, the ultimate prize was getting and maintaining party control—even if that meant handing out government jobs to inexperienced men, or using brass-knuckled tactics to win elections. Arthur and his cronies didn’t view politics as a struggle over issues or ideals. It was a partisan game, and to the victor went the spoils: jobs, power and money.

It was at Conkling’s urging, in 1871, that President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Arthur collector of the New York Custom House. From that perch, Arthur doled out jobs and favors to keep Conkling’s machine humming.

He also became rich. Under the rules of the Custom House, whenever merchants were fined for violations, “Chet” Arthur took a cut. He lived in a world of Tiffany silver, fine carriages, and grand balls, and owned at least 80 pairs of trousers. When an old college classmate told him that his deputy in the Custom House was corrupt, Chet waved him away. “You are one of those goody-goody fellows who set up a high standard of morality that other people cannot reach,” he said. In 1878, reform-minded President Rutherford B. Hayes, also a Republican, fired him.

Two years later, Republicans gathered in Chicago to pick their presidential nominee. Conkling and his machine wanted the party to nominate former president Grant, whose second administration had been riddled with corruption, for an unprecedented third term. But after 36 rounds of voting, the delegates instead chose James Garfield, a longtime Ohio congressman.

Conkling was enraged. Party elders were desperate to placate him, realizing that Garfield had little hope of winning in November without the help of the New York boss. The second place on the ticket seemed to be a safe spot for one of Conkling’s flunkeys; They chose Arthur, and the Republicans triumphed in November.

Vice President Chester A. Arthur. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Just months into Garfield’s presidency, Arthur’s meaningless post suddenly became critical. On the morning of July 2, 1881, a deranged office-seeker named Charles Guiteau shot President Garfield in a Washington railroad station. To Arthur’s horror, when Guiteau was arrested immediately afterward, he proclaimed his support for the Arthur-Conkling wing of the Republican Party—which had been resisting Garfield’s reform attempts—and exulted in the fact that Arthur would now be president. Some newspapers accused Arthur and Conkling of participating in the assassination plot.

Garfield survived the shooting, but he was mortally wounded. Throughout the summer of 1881, Americans prayed for their ailing leader and shuddered at the prospect of an Arthur presidency. Prominent diplomat and historian Andrew Dickson White later wrote: “It was a common saying of that time among those who knew him best, ‘Chet Arthur, President of the United States! Good God!’”

Big-city elites mocked Arthur as unfit for the Oval Office, calling him a criminal who belonged in jail, not the White House. Some of the people around Arthur feared that he was on the verge of an emotional collapse.

The newspapers were vicious. The Chicago Tribune lamented “a pending calamity of the utmost magnitude.” The New York Times called Arthur “about the last man who would be considered eligible” for the presidency.

At the end of August 1881, as Garfield neared death, Arthur received a letter from a fellow New Yorker, a 31-year-old woman named Julia Sand. Arthur had never met Sand, or even heard of her. They were complete strangers. But her letter, the first of nearly two-dozen she wrote to him, moved him. “The hours of Garfield’s life are numbered—before this meets your eye, you may be President,” Sand wrote. “The people are bowed in grief; but—do you realize it?—not so much because he is dying, as because you are his successor.”

“But making a man President can change him!” Sand continued boldly. “Great emergencies awaken generous traits which have lain dormant half a life. If there is a spark of true nobility in you, now is the occasion to let it shine … Reform!”

Sand was the unmarried eighth daughter of Christian Henry Sand, a German immigrant who rose to become president of the Metropolitan Gas Light Company of New York. She lived at 46 East 74th Street, in a house owned by her brother Theodore V. Sand, a banker.

As the pampered daughter of a wealthy father, Julia read French, enjoyed poetry, and vacationed in Saratoga and Newport. But by the time she wrote Arthur she was an invalid, plagued by spinal pain and other ailments that kept her at home. As a woman, Julia was excluded from public life, but she followed politics closely through the newspapers, and she had an especially keen interest in Chester Arthur.

The “reform” she was most concerned about was civil service reform. Under the so-called “spoils system,” politicians doled out government jobs to loyal party hacks, regardless of their qualifications. Reformers wanted to destroy the spoils system, to root out patronage and award federal jobs based on competitive examinations, not loyalty to the party in power.

Vice President Arthur had used his position to aid Conkling and his machine—even defying President Garfield to do so. There was every reason to believe he would do the same as president.

But Garfield’s suffering and death, and the great responsibilities that had been thrust upon him, changed Chester Arthur. As president, the erstwhile party hack shocked everybody and became an unlikely champion of civil service reform, clearing the way for a more muscular federal government in the succeeding decades. Arthur started rebuilding the decrepit U.S. Navy, which the country desperately needed to assume a greater economic and diplomatic role on the world stage. And he espoused progressive positions on civil rights.

Mark Twain, who wasn’t bashful about mocking politicians, observed, “it would be hard indeed to better President Arthur’s administration.”

Arthur’s old machine buddies saw it differently—to them, he was a traitor. Meanwhile, reformers still didn’t completely trust that Arthur had become a new man, so he had no natural base of support in the party. He also secretly suffered from Bright’s disease, a debilitating kidney ailment that dampened his enthusiasm for seeking a second term. The GOP did not nominate him in 1884.

Arthur was ashamed of his political career before the presidency. Shortly before his death, he asked that almost all of his papers be burned—with the notable exception of Julia Sand’s letters, which now reside at the Library of Congress. Arthur’s decision to save Sand’s letters, coupled with the fact that he paid her a surprise visit in August 1882 to thank her, suggests that she deserves some credit for his remarkable transformation.

Arthur served less than a full term, but he was showered with accolades when he left the White House in March 1885. “No man ever entered the Presidency so profoundly and widely distrusted as Chester Alan Arthur,” newspaper editor Alexander K. McClure wrote, “and no one ever retired from the highest civil trust of the world more generally respected, alike by political friend and foe.”

Scott S. Greenberger’s biography of Chester A. Arthur, The Unexpected President, was published by Da Capo Press last month.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Arizona State University, produced by