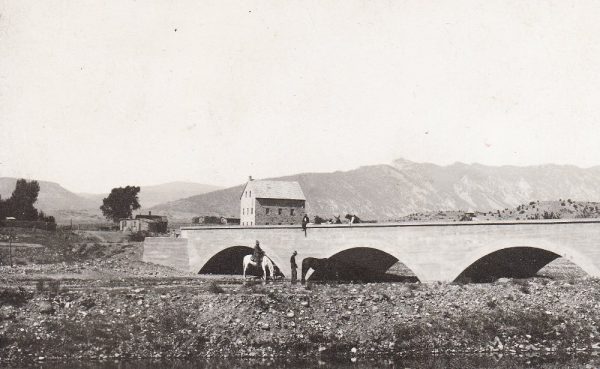

The northern New Mexico estate of Lucien B. Maxwell as it appeared c. 1905. Photo courtesy of William S. Kiser.

This system of unfree labor came into existence in the 1700s, when the region was still a colony of Spain. By the time that American military forces occupied the area in 1846, during the Mexican-American War, debt peonage had become deeply entrenched in society and culture. The United States thus inherited the system when, as a result of that war, it gained permanent possession of what is today California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and New Mexico. Peonage would persist there even after the Civil War, demonstrating the complexities of America’s struggle for abolition.

Peonage was especially prominent in New Mexico, where lower-class citizens often fell into debt out of sheer necessity. Sometimes a small loan from a wealthier landholder would be necessary for basic subsistence or shelter. Just as commonly, a debt originated with Roman Catholic priests, who charged exorbitant amounts of money to perform weddings, baptisms, and funerals. In order to marry one’s sweetheart, anoint a child in the church, or bury a deceased relative, a cash-poor person had no choice but to seek a loan from a person of financial means.

Those loans bound men and women to servitude in repayment of debt. The interest rates were manipulated in such a way that the full amount could never be repaid, thus ensuring a lifetime of bondage to one’s creditor. Servitude was hereditary. When peons died before the obligation had been satisfied, their children could be forced to labor for the same master.

Unlike slavery in the American South, peonage in New Mexico had no racial prerogative. In fact, peons shared much in common with their masters, including nationality (all were considered citizens), race and ethnicity (all were Hispanic), language (all spoke Spanish), and religion (all were Catholic). The most significant difference between master and servant was socioeconomic status and land ownership.

People who fell into servitude as peons were forced to conduct a variety of tasks, which typically depended on age and gender. Women and children usually did domestic chores within a household. Working-age men would be sent into the fields at planting and harvesting times, or into the pastures and prairies to tend flocks of sheep or herds of livestock.

The most well-known example of this hacienda-style aristocracy was the vast spread of Lucien Bonaparte Maxwell. On his immense land grant in northern New Mexico, Maxwell had hundreds of peons who tended his herds and tilled his fields in the Cimarron River Valley.

When American newcomers traveled through antebellum New Mexico, they could not help but draw comparisons between places like Maxwell’s estate and slave plantations in the South. After reading comparisons between debt bondage and chattel slavery, and learning of New Mexico’s statutory protection of involuntary servitude, Northern abolitionists took aim at peonage in the 1850s. Newspaper editorialists informed readers that the institution resembled the South’s chattel slavery. “It applies to all colors, shades and complexions, from the pure white to the sooty African,” wrote one New Yorker. “The creditor has as much command over the labor of the debtor, as the Southern slaveholder has over that of the negro.”

Similar comparisons arose in Congress, where one northerner gave a speech proclaiming that New Mexico’s peons “are in a worse condition of slavery than our negroes, and would be happy to change places with them.” Even U.S. Representative Thaddeus Stevens, one of the nation’s most outspoken abolitionists, targeted this alternative system of slavery. “Peonage,” he quipped, “saves the poor man’s cow to furnish milk for his children, by selling the father instead of the cow.”

Such negative publicity struck fear in New Mexico’s servant-holding class. So in 1851, the territorial legislature passed a law to protect debt peonage against the onslaughts of antislavery activists. This so-called “Master-Servant Law,” in laying out the legal parameters for relations between creditors and debtors, borrowed some of its provisions from slave codes and fugitive slave acts in the United States.

Under this new law, peons who failed to perform assigned tasks could be imprisoned at the request of the master. Local authorities had a legal obligation to chase down, arrest, and punish runaway peons. Masters were also protected from criminal prosecution in the event that they abused a servant who refused to work or attempted to escape. The law concluded with an ode to the patriarchal nature of the system: “all male or female servants shall respect their masters as their superior guardians.”

The overarching national significance of the controversy over debt peonage would not become clear until the 1860s, when the Civil War and Reconstruction prompted a seismic shift in the nature of American democracy. In 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution specifically prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude.

This landmark event has traditionally been viewed as the moment at which slavery ceased to exist in the United States. In the Hispanic Southwest, however, peonage outlived the Thirteenth Amendment because masters defined debtor servitude as a strictly voluntary condition of labor and ignored the new emancipation order.

The defiance of New Mexico’s “slaveholding class” drew the immediate attention of Radical Republicans in Congress, as well as President Andrew Johnson. A nation that had fought a Civil War for the principles of freedom and democracy could not, in these men’s eyes, continue to tolerate involuntary labor, in any form. In direct response to the persistence of peonage in the Southwest, Congress passed an act in 1867—and Johnson quickly signed it into law—that explicitly banned peonage throughout the United States. Largely as a result of this federal “Peon Law,” the peculiar institution of debtor servitude, which had existed in New Mexico for generations, reached its gradual end. By the 1870s, most peons had been freed.

The country’s transition from slavery to free labor was not nearly as simple as an Emancipation Proclamation or an amendment to the Constitution. Other forms of bound labor—including debt peonage—survived the war, and prompted a sweeping legal and political reassessment of how Americans defined involuntary servitude. It also brought a deeper understanding that slavery was and would remain an American problem that would require sustained attention, because it transcended any particular era or ethnic group.

The abolition of peonage is a reminder of the political discord that attended the 19th-century struggle to emancipate more than four million slaves, which included not just African Americans but also Hispanics and even Native Americans. This fight to eliminate alternative modes of enslavement symbolized the nation’s ongoing resolve to form a more perfect union wherein the Constitutional ideals of freedom encompassed an increasingly diverse range of citizens.

The emancipatory crusade that started with the nation’s first peon law in 1867 remains imperfect. Various permutations of peonage still exist in the 21st century, prompting repeated amendments to the U.S. Code. The most recent modification, added in October 2000, mandates that “whoever holds or returns any person to a condition of peonage” will be subject to stiff penalties, including fines and up to 20 years’ imprisonment.

Today, debt bondage is commonly associated with human trafficking and is especially prominent in California, where thousands of undocumented immigrants from Asia and Latin America are indentured into long-term conditions of subversive sweatshop labor and even prostitution. Thus, the abolition of coercive servitude and the expansion of human rights that began in the Civil War era is an unfinished social and cultural revolution in which American citizens continue to play an active role.

William S. Kiser is an assistant professor of history at Texas A&M University-San Antonio. He is the author of Borderlands of Slavery: The Struggle over Captivity and Peonage in the American Southwest, published by the University of Pennsylvania Press.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History