The author borrowed a Norwegian sweater, knickers, and a bunad to stage this photo in front of a quaint hytta to show everyone back in the Midwest that his family was fitting right in in Trondheim. Photo courtesy of Arild Juul.

I braced myself to hear the usual stereotypes from the news from the Norwegian students in my class. Then the professor clarified, “What to you is truly good about America?”

Even though I’m an American, I was stumped. I mentioned the clichés of “liberty,” “melting pot,” “representative government.”

My Norwegian classmate Astrid was much more awake: “What about your Constitution?”

“The Freedom of Information Act!” exclaimed Dag, an outspoken intellectual with his hair slicked stylishly forward. “That is what makes America great.”

I realized that Dr. Mauk was actually leading us to one of the big questions of the day in Norwegian newspapers: What did it mean to be “Norwegian?” This was especially relevant because thousands of new immigrants had recently arrived in Norway, to a less-than-enthusiastic welcome. What I didn’t realize was how this question would help me understand my place in my own country.

Like many Americans, my great-grandparents escaped poverty and underwent a grueling ocean voyage to seek a better life. They came from Scandinavia, 125 years ago, and settled in Wisconsin and Minnesota. I had thought of this past as a curiosity rather than having much bearing on who I am today. Now that I was living in Norway for a year—and relying on its great socialized medicine and free university tuition—I, too, was one of the new foreigners. The word in Norwegian for us was “innvandrere,” which sounds like “invaders.” My classmate Sophie pointed out that “No, it’s ‘vandre.’ That’s more like wander, so it’s people who wander in.”

Sophie assured me that I wasn’t a foreigner in Norway; I was Norwegian, because my great-grandfather was born here. She and others in Norway referred to Minnesota, Wisconsin, North Dakota and other cold spots as Norway’s “colonies” in America. I was simply a colonist returning to the homeland.

I insisted that I was American, just with Norwegian roots and last name. But during my time in Norway, I slowly realized that many traits that I considered Minnesotan were essentially Scandinavian. Our art of avoiding confrontation and being passive aggressive to bring down people who think too much of themselves is reflected in the Nordic idea of janteloven, which enforces the “law” that you are no better than anyone else, so get your nose out of the air and put it to the grindstone. The Minnesota accent is Scandinavian or Germanic, and Midwestern linguistic peculiarities such as leaving prepositions to dangle come right from Norwegian (“Do you want to come with?”). Like Scandinavia, our government in the upper Midwest is remarkably clean and free of corruption. All we need is Nordic universal health care.

To appease the others in my class, I gave up arguing over whether I’m truly Norwegian or American. I realized this debate signaled that they accepted me, even though other new immigrants seemed to be excluded. While Sophie was positive about my “Norwegianness,” she wasn’t sure about Professor Mauk. He spoke the language fluently (as opposed to my halting Norwegian), lived in Norway, was even married to a Norwegian, but, without ancestors from Norway, definitely was not Norwegian.

Professor Mauk replied, “People keep asking me if I have become a Norwegian citizen yet, so I thought up a pat answer, ‘Would you consider me more Norwegian then?’ They pause to wonder if it’s a trick question and then reply, ‘Probably not.’ Then they stopped asking if I’ve become Norwegian.” He was American, according to them, even if he knew far more about Norway than I.

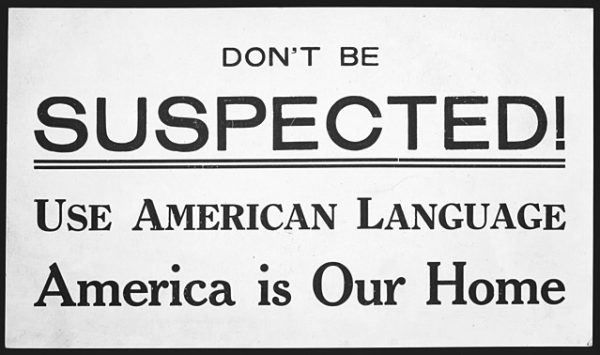

Warning posted at Scandinavian lodges and elsewhere advising against using foreign languages during WWI. It suggested that people speak “American,” rather than “English.” Image courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society.

Back in the American Midwest, many people refer to themselves as simply “Norwegian” or “Swedish,” not “Norwegian-American” or “Swedish-American,” even though many have never been to Scandinavia and can’t speak the language. Most are third-, fourth-, and even fifth-generation Scandinavians who can decide which of their many different backgrounds they want to claim. Ethnicity in America becomes a choice when one has more than one background.

In the past, though, the U.S. government viewed these “hyphenated Americans” with suspicion. When World War I broke out, suddenly no one was German in Minnesota, even though it’s the largest ethnic group. Scandinavians were viewed with equal distrust. My grandfather spoke a mixture of Swedish and Norwegian at home (“Svorsk”) until he went to kindergarten—where he was punished for not speaking English, a language he didn’t know. One child in the class translated for the rest of the kids. When I asked why my grandfather didn’t pass on the “old language,” he told me solemnly, “We’re in America; we speak English now. It’s better that way.”

During World War I, speaking foreign languages in the U.S. was considered tantamount to treason. Posters mounted in ethnic lodges warned, “Don’t be SUSPECTED! Use AMERICAN LANGUAGE. America is Our Home.” The Minnesota Commission of Public Safety had the power to jail anyone speaking out against the war or for “the idea of peace.” The government set up “Americanization” committees to force immigrants to give up their hyphenated identities by abandoning their old citizenship and culture and becoming Americans and only Americans. My great-grandparents arriving in the Midwest were ultimately able to assume a new identity of being “American,” if they wanted. However, today’s new immigrants to Norway may never have the option of being considered Norwegian.

Remnants of Norwegian culture remain and are treasured in the Midwest, but my family lost the language, though some of us have struggled to learn it again. One Lutheran parishioner joked to the author of They Chose Minnesota about being forced to give up his native tongue, “I have nothing against the English language. I use it myself every day. But if we don’t teach our children Norwegian, what will they do when they get to heaven?”

Would I have learned all of this if I hadn’t lived in Norway? I feel that only through living abroad was I able to appreciate this complicated history and discover my place as an American. While I feel comfortable with this label, many people in the Midwest call themselves simply Norwegians without the hyphen. I told Helen, another university student, about this and how many of these “Norwegians” in Minnesota have never been to Norway and can’t speak a word of the language.

Without a hint of irony, she responded. “Then you, too, are Norwegian now.” I argued that I’m American with Norwegian roots, but she didn’t agree. “You were Norwegian first,” she insisted.

Eric Dregni is the author of In Cod We Trust, Vikings in the Attic, and most recently You’re Sending Me Where? Dispatches from Summer Camp.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Arizona State University, produced by Zócalo Public Square.