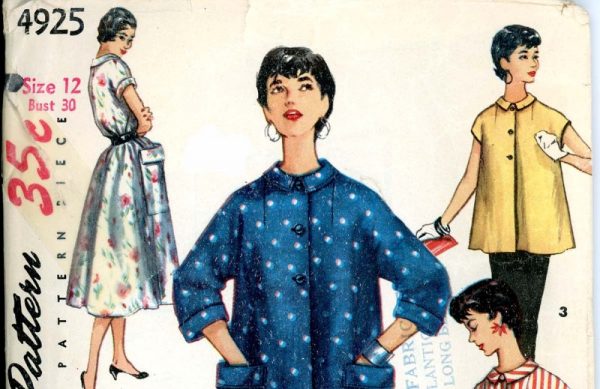

Patterns were often classics that would not quickly be out of style and could accommodate different sizes. Image courtesy of the Commercial Pattern Archive.

It seems surprising now, but once the use of cloth feed bags for clothing and household items was a part of mainstream rural American culture—related to a long practice of utilizing all resources that is deeply imbued in the American psyche. Resourceful housewives recycled feed bags from flour, corn, sugar, salt, and even chicken feed into children’s’ clothes, aprons, and dresses.

At the outset, feed bag clothing was strictly utilitarian; in the Great Depression, it became a symbol of thrift and economical household management, and during the war years in the 1940s its use was promoted as part of the campaign for Allied victory. The rise and fall of the feed sack dress tells a story about a culture that once deeply valued both thrift and ingenuity. It is also a story of how commercial interests—cloth makers, feed sellers, bakers, pattern makers, and even newspapers—were keenly aware of the large, if indirect, market for such thrifty clothes.

Starting in the mid-1800s, cloth bags became a recognized resource for clothing. Foodstuffs were packaged in a range of five- to 100-pound sacks; the latter measured 36 by 42 inches. Originally made of burlap or osnaburg—a coarse off-white plain fabric that softens with subsequent washings—they were ideal for men’s, women’s, and children’s undergarments and nightwear as well as utilitarian household accessories.

Feedsack Dress made by Mrs. Dorothy Overall of Caldwell, Kansas, in 1959. Photo courtesy of The National Museum of American History.

In the early 1930s, with the onset of the Great Depression, bag manufacturers added colors and prints, along with the traditional white bag that could be dyed—to attract more farm wives. Their husbands were instructed to buy feed bags in specific colors and prints in order to get sufficient yardage for garments.

Patterns for garments specifically made from feed bags were promoted in advertising pages of newspapers. Companies such as Famous Features in New York City produced numerous patterns with different brand names such as Barbara Bell, Sue Barnett, and others from circa 1923 to 1997. The collaboration was designed to attract the farm housewife to specific products.

In partnership with National Cotton Council, bag manufacturers produced national publications such as “Bag of Tricks for Home Sewing” and even promotional flyers to insert in loaves of bread. Patterns shown in the publications specified the number and size of bags needed to make each garment. These designs were not subject to the latest fashion trends but featured timeless fashions that gave them a surprisingly long lifespan. For example, the pattern for the pajamas that the church ladies presented to President Coolidge was still in circulation in 1945.

I learned details about the feed bag clothing innovation from publications and patterns in the Commercial Pattern Archive at the University of Rhode Island. Daniel Flint, owner of Famous Features, explained in an interview that their styles were basic and intended to last for several years. Not all patterns are tagged specifically for the use of feed bags but many can be used that way.

Enterprising women formed clubs to collect and exchange bags; purchasers sought specific matching colors and a textile design to meet the yardage needs. Bakers realized they could sell their flour bags, so they bought specific dress goods bags and shipped them to millers to be filled with flour. After emptying the bags, they made up home sewing kits with four matching cotton bags, eight buttons, thread, and a pattern book.

One of the most popular garments that could be made from bags was an apron; some designs were simple, while others were fancier. Other popular garments included mother/daughter fashions, infant’s and children’s wear, toys, draperies, slip covers, closet organizers, maternity, and undergarments.

The child’s dress prominently and unusually displays the product logo. Photo courtesy of the Commercial Pattern Archive.

Producers identified their product with company logos on each bag. Ideally these needed to be removed, which usually required soaking the bag overnight in cold water then washing in warm soapy water and possibly boiling for 10 minutes to restore color. Removal of the logos was considered essential to avoid announcing the source of the fabric and any related stigma of poverty and “home-sewn.” On rare occasions, the logo was a feature of the design such as that worn by the little girl (pictured right).

A major contributor to the endurance of clothing from bags during World War II was textile restrictions imposed in support of military needs. The restrictions did not impact feed bag manufacturers because the bags were designated in the “industrial” category. Therefore, the high quality textiles used for feed bags were in abundance for the home sewer. Consequently, feed bag clothing became even more popular during World War II.

According to “Bag of Tricks for Home Sewing,” by the end of the war more than 800,000,000 yards of cotton fabric each year were made into bags. In “Bag Magic for Home Sewing” (1946) the National Cotton Council declared feed bag clothing to be the “warp & woof of daily life, the simple virtues of thrift, ingenuity and skill—the virtues upon which in the last analysis, the future of the country rests.” In addition to recycling the bags, users were encouraged to save the string used to close the bags for crocheting; patterns were included in the booklets.

In the postwar years, the National Cotton Council and the Textile Bag Manufacturers Association concentrated on additional associations with two mainstream pattern companies and expanded the line of textiles to include percale, chambray, cambric denim, toweling, and rayon with a silky sheen. At the peak of the bags’ popularity, textile designers were hired to create exciting prints to attract consumers—both millers and the public. Bag manufacturers issued a wide range of textile colors and designs. In conjunction with Simplicity and McCall’s, they promoted national sewing competitions for adults and teens as well as traveling fashion shows featuring bag clothing through at least 1961.

The demise of feed bag clothing was brought about by the increasing popularity of less expensive paper bags, and in 1948 twenty states forbade re-use of cloth bags for food products. Combined with the increasing popularity of less expensive paper and plastic bags, the decline of farming populations, and increased availability of inexpensive ready-made clothing, this resulted in a low demand for cloth feed bags by the early 1960s. The cultural shift from primarily family-operated farms to large cooperatives resulted in many families moving to urban centers.

Fewer women were providing the family wardrobe, since ready-made clothing was readily available and more affordable. Home-made garments and gifts celebrating economy and thrift were no longer part of the American psyche.

Joy Spanabel Emery is professor emeritus at the University of Rhode Island, author of A History of the Paper Pattern Industry: The Home Dressmaking Revolution, and the curator of the Commercial Pattern Archive, which is the largest repository of patterns of everyday dress from the mid-19th century.

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Arizona State University, produced by Zócalo Public Square.