T. Pariseau Ladies’ Outfitter, one of many businesses created and owned by Franco-Americans in Manchester. Photo by Ulric Bourgeois, 1915.

“Franco-American, as in canned spaghetti?” some ask.

I roll my eyes and sigh. “No connection whatsoever.”

Geographically, Franco-Americans resemble Mexican Americans in the Southwest because we also live near our cultural homeland. But unlike Mexican Americans, we’re unknown outside our region. Quite accurately, Maine journalist Dyke Hendrickson titled his 1980 book about Franco-Americans Quiet Presence. The source of this inconspicuous group identity lies in our ethnically and religiously mixed relationship to the United States, Québec, and even pre-revolutionary France, which has given Franco-Americans a highly varied and personal sense of what our identity means.

From the earliest French expedition to the Carolinas in 1524, to the founding of Québec City in 1608, New France eventually extended across North America from the Appalachians to the Rockies, and south to the Gulf of Mexico. But over time, through conquests, treaties, and land sales, French North American colonies became part of the British Empire, or of the United States. The only exceptions were islands near Newfoundland and in the Caribbean, plus an independent Haiti.

For socioeconomic and political reasons, as second-class citizens under British rule in the very country they had founded, roughly 900,000 French Canadians left Québec between the 1840s and the Great Depression. Many settled in New England and eastern New York state. The earliest migrants, mostly farmers, engaged in agriculture or logging in rural areas, or in the manufacture of textiles, shoes, paper, and other goods in urban areas. After the Civil War, when migration increased drastically, members of Québec’s business and professional classes settled among their compatriots. Today, Franco-American descendants of the original French Canadian immigrants total more than three million.

Among the region’s mill towns, there emerged four with Franco-American populations significant enough to vie for the unofficial title of French-speaking capital: Lewiston, Maine; Manchester, New Hampshire; Lowell, Massachusetts; and Woonsocket, Rhode Island. These cities and others had Franco-American neighborhoods called Petit Canada (Little Canada), comprised of residences, churches, schools, businesses, social organizations, newspapers, and other institutions designed to preserve the French language and Franco-American culture. There, one could be born, educated, work, shop, pray, play, die, and be buried almost entirely in French. Streets with names such as Notre Dame, Cartier, and Dubuque were lined with multi-family houses in whose yards there might be a shrine to the Sainte Vierge Marie, the Sacré-Coeur de Jésus or to one’s favorite saint. From those homes came the aroma of tourtière (pork pie), tarte au sucre (maple sugar pie), and other delights.

Unlike other groups who’ve become well known, most Franco-Americans tend to live and practice their culture in intimate, unassuming, and conservative ways. In my opinion, the root of this unobtrusiveness lies in our history.

The 1789 French Revolution didn’t merely topple the king and replace the monarchy with a republic, it also attacked the Roman Catholic Church and made freethinkers of the French masses. Having left France a century earlier, our ancestors missed that Revolution.

Fast-forward to Québec’s Révolution Tranquille (Quiet Revolution) of the 1960s, which had somewhat the same effects on the previously Catholic-clergy-dominated Québécois as did the French Revolution on the French people. But by the time of that revolution, Franco-Americans were already living in the United States.

Yet even though the Franco half of our collective psyche missed both revolutions and remained in the past, the American half of our dual identity experienced the future-focused sociocultural revolution of the 1960s in the United States. This phenomenon applies mainly to baby boomers, whose Franco identity was already on the wane by the 1960s, while their American identity was susceptible to influences of the times, as is evidenced by the subsequent rise in outright secularism or, in adherents of cafeteria Catholicism, the rise in divorce, cohabitation, contraception, and other practices considered taboo by the Catholic Church.

In fact, each family—and each person, really—has a slightly different sense of what being Franco American is. Consider my hometown, Manchester, New Hampshire, where the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company (1831-1936) attracted immigrants from Québec and Europe from the mid-19th through the early-20th centuries. With Manchester’s total population at 78,384 (1920 U.S. Census), Amoskeag’s work force peaked at 17,000, some 40 percent of whom were Franco-Americans. At its highest, Manchester’s Franco-American population reached nearly 50% of the city’s total. To serve their needs, they created their own institutions—for example, eight parishes, all of which included a church and a grammar school, and in some cases, a high school. The social services sector comprised orphanages, hospices for the aged and the indigent, and a hospital.

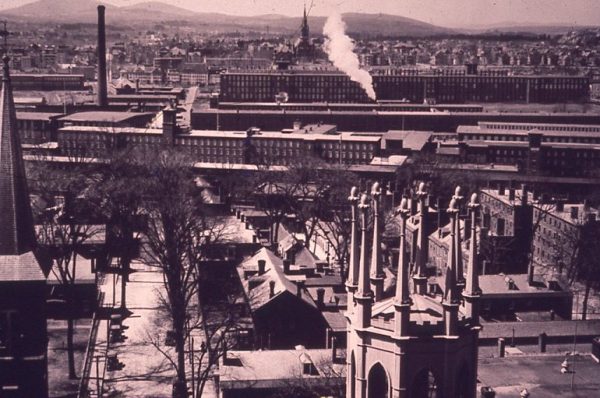

Bird’s-eye view of Manchester looking from downtown toward the mills of the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company and beyond to the Franco-American West Side. Photo by Ulric Bourgeois, 1925

I was born in 1951 and, unlike many Franco-Americans, my family lived across the Merrimack River from Manchester’s Petit Canada, where we were the French family among Scottish, Irish, Polish, Greek, Swedish, and other ethnicities. Although my father’s relatives spoke French, they favored English. Other than belonging to St. George, one of Manchester’s eight French-language parishes, they weren’t members of any Franco-American institutions. By contrast, my mother’s relatives spoke French exclusively and were heavily involved in various aspects of Franco-American culture. Out of respect for my maternal grandparents, French was the chosen language in our home when I was a young child.

My awareness of the difference between our family and others increased when I started school. Nearly every neighborhood kid attended either the public school around the corner from our house or an English-language parochial school somewhat farther away. Meanwhile, I attended St. George, which was Franco-American. There, French and English were taught to us on an equal level, each during its half of the school day. We had to be fluent in both languages upon entering first grade.

Our most important subject was catéchisme, almost as if French were the official language of heaven. Surprisingly, l’histoire du Canada wasn’t taught, nor was Franco-American history. In fact, I don’t recall the term Franco-American having ever been pronounced in class. And as for Acadians, a separate branch of French North Americans, I learned of their existence and that of their Cajun cousins only through my research as an adult!

These terms themselves show how difficult it is to describe the multi-faceted identity of being Franco-American. That term in French—Franco-Américain—is something my maternal grandfather, uncles, and aunts all used. My mother always said we were Canadiens, despite our having been born in the United States. Anglophone kids called us French, and some adults called us French Canadians and still do. Franco-American seems to be a term used mainly by community activists.

Nowadays, much of the daily culture that Franco-Americans once lived by is practiced outside the home during festivities such as the feast of the French Canadian patron saint, la Saint-Jean-Baptiste on June 24. In Manchester, one can eat some of the aforementioned traditional foods in a few restaurants, including the popular Chez Vachon, a must-stop for candidates during New Hampshire’s first-in-the-nation presidential primary. There, the specialty is poutine (French fries and cheese curds in gravy), a late-20th-century Québécois invention some call a heart attack on a plate.

Franco-American identity manifests itself more strongly through organizations such as the Franco-American Centre/Centre Franco-Américain, which offers French classes, films, lectures, and other events, and the American Canadian Genealogical Society, where Franco-Americans from all over the United States come to Manchester to trace their ancestral roots.

With every generation, most Franco-Americans have put a bit more American water in their French wine. Many today don’t speak French and know little about their ethnic heritage. In the United States, pressure from proponents of the English language and American culture has accelerated this evolution. Whereas people once spoke French on the street, in stores, in restaurants, and elsewhere, and whereas Manchester almost always had a Franco-American mayor, such phenomena are now things of the past.

Though many Franco-Americans are such in name only now, our family is an exception. My wife is the first woman I ever dated who introduced me to her mother in French. We raised our son in French. He and his wife, a former student of mine, are doing likewise, the seventh generation of French-speaking Perreaults living on U.S. soil.

To us and to a minority of Franco-American families in our region, the French language and our Franco-American culture are gifts we lovingly pass on from generation to generation.

Robert B. Perreault has taught conversational French at St. Anselm College, Manchester, New Hampshire, since 1988. He is the author of a French-language novel, L’Héritage (1983), set in Manchester’s Franco-American community, Franco-American Life and Culture in Manchester, New Hampshire: Vivre la Différence (2010), and a new book of his original photos, Images of Modern America: Manchester (October 2017).

This essay is part of What It Means to Be American, a project of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and Arizona State University, produced by Zócalo Public Square.